Indigenous have faced a culture of racism and discrimination that goes back centuries

When California’s Central Valley leaders of Mixteco origin learned about the racist comments made by three Latinos on the Los Ángeles City Council regarding the Oaxacan Indigenous community in October 2022, they were not surprised.

After all, those insults against the indigenous are nothing new and are part of a culture of racism and discrimination that goes back centuries.

“We have always experienced discrimination and oppression from Latinos themselves,” said Oralia Maceda, program director of El Centro Binacional para el Desarrollo Indígena Oaxaqueño in Spanish in October.

Culture of racism

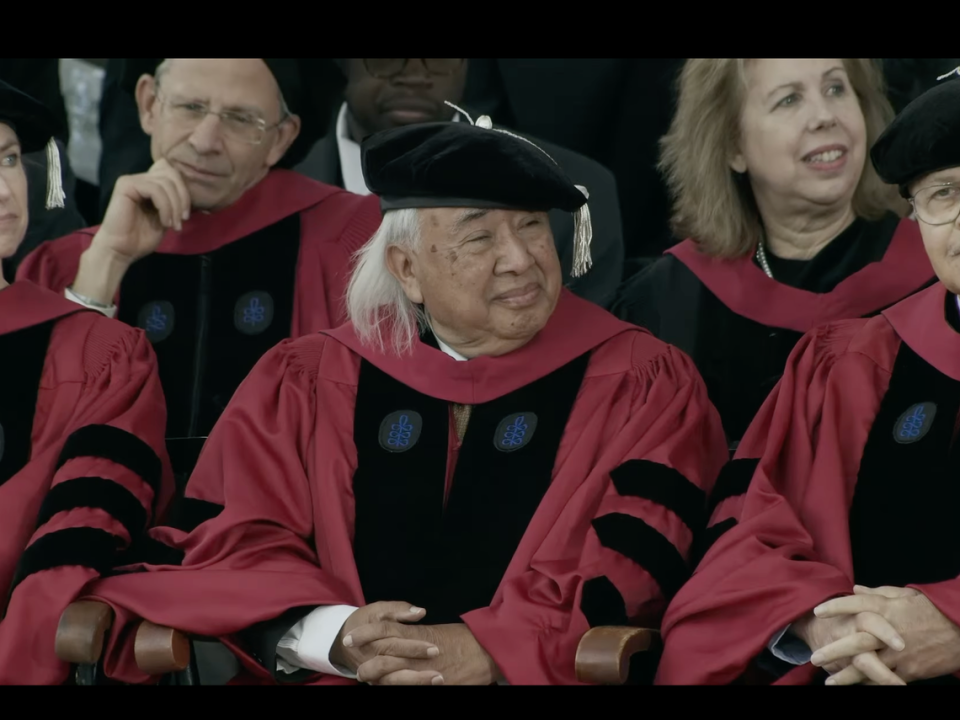

Hugo Morales, co-founder and executive director of Radio Bilingüe, said culturally, discrimination and racism against indigenous people is something that has taken place since colonial times when white people invaded and conquered México and Latin América “instilling their own culture of racism.”

The 74-year-old Morales, who is of Mixteco descent, said after the Spaniards invaded México and Latin América, they wrote a legal code of hierarchy placing pure whites from Spain at the highest order above Blacks and native Americans.

“That was literally part of the legal system in colonial times throughout, you know, Latin América that was ruled by Spain, which is most of the Américas,” Morales said. “So, you know, that racism was embedded there.”

The racist, anti-indigenous comments by Los Ángeles City Council President Nury Martínez, along with Councilmembers Gil Cedillo and Kevin de León, among others, were caught on audio and leaked near Columbus Day. The holiday is referred by Morales and other indigenous as the “the anniversary of (Christopher) Columbus’ march of colonization and genocide.”

Recently, Columbus Day has increasingly been replaced with Indigenous Peoples’ Day, which honors and celebrates the history and culture of indigenous people of the Américas.

“We are in the commemoration of 530 years of resistance of our Indigenous communities and we are still experiencing those bad experiences that we have as (Indigenous) communities,” said Maceda, who is of Mixteco origin.

In the leaked audio, councilmembers refer disparagingly to the appearance of immigrants from Oaxaca, calling them ugly, short, and dark-skinned.

California is home to about 350,000 Indigenous Oaxacans, who are mainly concentrated in the Central Valley, the southern part of the state and the Monterey area, according to a 2016 study by USC and the Mexican research institute El Colegio de la Frontera Norte.

Racism and discrimination can evolve to hate speech and hate crimes. State officials have noted an increase in hate crimes in recent years among all ethnicities and sexual orientation.

The indigenous have been discriminated against because of their language, culture, stature, dress or indigenous features they have.

“I think that racism among Mexican mixed bloods is so deep that it doesn’t matter how a person dresses,” said Morales, adding that people find a way to discriminate.

For example, the Monterey County community of Greenfield, where about one in three residents are Oaxacan indigenous migrants, made the news in 2011 when national media reported an “ugly conflict” between long-time Latino residents and Oaxacan newcomers who spoke their own languages, and kept their own customs such as arranged marriages to daughters still in their teens.

Latinos, mostly Mexican Americans, were unhappy with the new immigrants and presented a series of escalating grievances against the Oaxacans to the city council, social media sites and the local newspaper.

Elsa Mejía, the first Mixteca elected to a U.S. city council, has endured slurs like those made by Los Ángeles leaders since childhood.

“It didn’t stop when I was a child. It happened in social settings as a teenager. It happened in the workplace and it continues to happen,” Mejía said.

At one entry level job, the manager who was Mexican called Mejía “Indita” (Little Indian.) and nobody said anything about it.

“So that was very disappointing. It was heartbreaking, painful and angering to have experienced that in the workplace setting where all of us were supposed to be treated equally,” said Mejia, who is currently in the Madera City Council. Madera, the county seat, has a large and influential Oaxacan population.

The “-ita” is added at the end of the words as a term of endearment, but the terms become insults when paired with words directed at México’s Indigenous.

“I think that when people stay silent and they see that you’re going through something like that, they’re also accomplices to the person that is attacking you,” said Mejía.

“So there is a lot of work to be done around educating, you know, the community in general and decolonization of mindsets,” said Mejía, a first-generation college graduate.

Mejía said everyone’s experience is different when it comes to racism and discrimination.

Herself being Mexican American, indigenous born in the U.S., Mejía said, is different from other indigenous people like her parents who migrated from Santa María Tindú in the Mixteca region of Oaxaca in their youth.

“We are experiencing this differently. We have different obstacles,” she said. “I know that our parents had the greatest hardship of physically coming here, but that doesn’t mean that, you know, obstacles stop for us.”

“We still have to break through so many barriers, including institutional barriers, college or being in places like city council or just all these new places for us, it’s like all of these different barriers,” said Mejía, who in 2021 lost an opportunity to be appointed to fill a vacancy on the council. One council member said she was not qualified because she has never been a mother.

Mejía said she recognizes and acknowledges that she has “light-skinned privilege”.

“A lot of people didn’t always right away identify that I was Oaxacan myself because they have that prejudice,” Mejía said. “They think that everyone from Oaxaca is supposed to be a certain type of way, and we’re not.”

When media perpetuate racism

Morales said media companies (he mentioned Televisa or Univision) – through movies, programs and novelas – continue to perpetuate racism and discrimination against indigenous people.

For example, Morales said, the character La India María – which is popular in México – degrades indigenous people.

He said media companies also use the words like ‘Oaxaca” and “Oaxaqueños” as being the defining entity representing the indígena (indigenous), plus there are still television programs or series that make fun of indigenous people.

“And you know it’s considered normal,” Morales said.

Morales said that racism is used by Mexican commercial media to draw an audience and to feed the racism, and the worst of Mexicans and Latinos, for the sake of the ratings.

He said television, radio and print news media in México are very comfortable “in discriminating and portraying us as, you know, as undesirables or ridiculing us and to build audiences.”

The racism in México, Morales said, is not just around indigenous and blacks, but also the Chinese.

Morales said some radio stations (he mentioned Univision Radio) use a lot of the term ‘El Chinito (little chinese)’ which it’s all tied to racism against indigenous, a term that he is very well familiar with since it has been used against him many times.

“It’s racism, a play off, Mexicans are racist against Chinese, but they’re also racist against indigenous,” he said.

“Mixed bloods take a joy out of insulting indigenous people by calling them chinitos when in fact they know they’re not chinitos. But that’s what they use as a way to insult and degrade people, you know, in your face,” Morales said, adding that it is so ingrained by the media that people see it as normal.

Seeing how commercial media treat indigenous, Morales said that is why Radio Bilingüe highlights the voices of Mixtecos and Mixtecas every Sunday - with music, language, culture – a program that is transnational, being broadcast in their own homeland in Oaxaca and are respectful to its audiences, all indigenous.

“So, this is our way, one of our ways of lifting the voices of indigenous, of educating our other audiences who are mixed bloods and other people about, you know, what value we place in our listeners who are indigenous and they are capable of doing our radio show and projecting and speaking for themselves and advocating for ourselves and celebrate our own culture, our own language and so forth,” Morales said.

A sense of pride: Breaking the culture of racism

Decolonization – breaking the culture of racism – begins with “education of not just the community in general, but even ourselves within our indigenous families,” said Mejía, a former journalist.

Her parents always instilled in her siblings and herself “a sense of pride of being mixteco,” Mejía said.

Mejía said indigenous parents teaching the next generation of indigenous born in the Valley like herself about their culture’s practices, traditions, customs beliefs and “that sense of pride, of being mixtecos,” arm their children at home with the knowledge.

“And that empowers them in the event that they are bullied,” Mejía said.

However the job or the challenge of breaking the culture of racism shouldn’t fall only on the indigenous community, said Morales and Mejía.

“It’s not us, you know, it’s the other. It’s not the victim. It’s the perpetrator that, you know, we should focus on,” said Morales, who has lived in the United States since he was 9 years old.

From his own experience, Morales said he has faced less discrimination among white people than Latinos or Mexican Americans.

“Where I’m more appreciated, frankly, for my accomplishments are more white people,” Morales said. “It’s just sad. It’s not that white people are not racist because there is a lot of racism among white people. But the racism in Mexico continues unabated.”

Mejía said she heard that in Madera Unified there is education going on about “our large concentration of Indigenous people here in Madera.”

“The community in general needs to know who we are and that respect is important. And respect is a two way street,” Mejía said.

It’s been a long process, she said, “but just even having the conversation, that narrative in the media haciendo conciencia (raising awareness) it’s making progress.”

Comparing it to when she was younger to now, Mejía, who is in her 30s, said there is a sense of pride.

“People are uplifting our community. They’re not being ashamed of who they are and just celebrating who we are,” Mejía said. “And I think that La Guelaguetza Madera is one example of many that are happening right now.”

This is part of a series on Stop The Hate, a project funded by the California State Library.

Fresno police chief: Low reports of hate crime don’t tell the whole story

Protecting a diverse city from hate crimes a priority for Fresno mayor

Task force to tackle growing problem of hate crime in the greater Fresno area

Coming out in Fresno: For queer Latinos, supportive families are ‘bigger than everything’