Indigenous nations in Wisconsin are represented in a new exhibit at Chicago's Field Museum. Here's what's featured.

CHICAGO - Karen Ann Hoffman, a citizen of the Oneida Nation in Wisconsin, believes the craftsmanship from her tribe is not as well known as that of southwestern tribes, such as the Navajo, but is hopeful that’s about the change.

“Eastern Native art doesn’t get the respect I think it deserves,” she said. “And Haudenosaunee (Oneida) beadwork tends to get even less respect.”

That’s why she was ecstatic to have four of her Oneida beadwork masterpieces set on display at Chicago’s Field Museum for a new, permanent exhibit.

The museum saw more than 600,000 visitors in 2021 despite the pandemic, so Hoffman knows her beadwork will have high exposure.

The new renovated hall at the Field Museum, called Native Truths: Our Voices, Our Stories, opened in May.

“I’m so excited to be here,” Hoffman, 64, said at the opening celebration.

Her beadwork was nationally recognized in 2020 in what is considered the country’s highest honor in traditional arts by the National Endowment for the Arts.

RELATED: Oneida woman wins national award for beadwork, art to be shown at Chicago Field Museum

Oneida beadwork is visually different from other beadwork in that the beads are raised and arch above the textile surface to create a three-dimensional effect.

During her journey with the art form, Hoffman was amazed to discover an ancient Indigenous piece about 8,000 years old in the New York State Museum that featured designs still used in the artwork today. The Oneida are originally from what is now upstate New York.

Hoffman also sees her beadwork as potentially transcending generations and helping to keep Haudenosaunee culture alive.

She incorporates cultural stories or lessons into her beadwork through important symbols or animals.

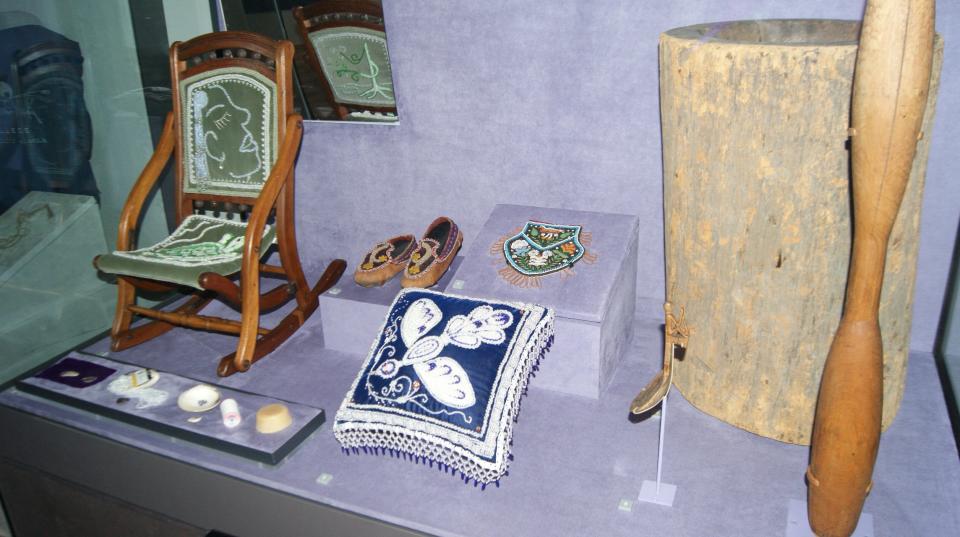

Hoffman’s four pieces on display at the Field Museum are representative of the four seasons and includes a chair with a depiction of “Sky Woman,” which is part of the Oneida world creation story. Another piece includes the mythical Thunderbird.

Hoffman also narrates a summary of Indigenous history in another part of the exhibit.

Sign up for the First Nations Wisconsin newsletter Click here to get all of our Indigenous news coverage right in your inbox

The new hall at the Field Museum includes representation from 105 different tribal nations across the U.S., including three from Wisconsin: Oneida, Menominee and Ho-Chunk. Its 40 displays include about 400 items.

And 130 Indigenous collaborators worked to help set up the exhibit, including Doug Kiel, who’s also a citizen of the Oneida Nation in Wisconsin and helped co-curate.

"Kanolukhwásla is one of my favorite words in Ukwehuwehnéha, the Oneida language,” Kiel said. “Love is the root word, and it means compassion, caring for others, and the joy of being one's identity. In this space, Native people from all over Turtle Island (North America) celebrate their gifts and speak their truths."

Menominee contribution

Menominee Tribal Enterprises, which operates the lumber mill on the Menominee Reservation, installed the floors of the new hall at the Field Museum.

Lumberjacks working for the company also recently harvested a 191-year-old eastern white pine tree that was made into benches for the Field Museum exhibit.

And a “tree cookie” showing the rings of the tree is on display telling a story. Near the first ring when the tree was young is a photo of Chief Oshkosh, who was instrumental in helping to keep the Menominee Tribe from being forcefully relocated out of the land now known as Wisconsin, the Menominee homeland.

Toward the outer rings from modern time is a photo of Ada Deer, who was instrumental in restoring the tribe’s federal recognition status in the 1970s after it had been terminated in the 1950s.

Deer, 86, was a featured speaker at the opening celebration in May at the Field Museum.

“A friend said, ‘You Menominee are always talking about your trees,'” Deer said. “The Menominee people are deeply attached to our forest. The land is everything to us.”

The Menominee Forest on the Menominee reservation is often touted by experts as the largest single tract of virgin, native timberland in the Great Lakes region. Its natural resources provide a trove of benefits to Wisconsin and it's seen as an example of how a forest should be managed.

RELATED: 'Our spiritual home': Wisconsin's pristine Menominee Forest a model for sustainable living, logging

Menominee officials also planted a “peace tree” outside the Field Museum for the celebration and Oneida spiritual leader Bob Brown explained the significance of the tree in the Oneida language during the event.

The eastern white pine is known as a “tree of peace” to the Oneida and the other tribes that make up the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) that had once been at war with each other.

The tribes marked their alliance as the Iroquois Confederacy during the 1400s by burying their arrows in the roots of the tree pointing in the four directions.

Ho-Chunk contribution

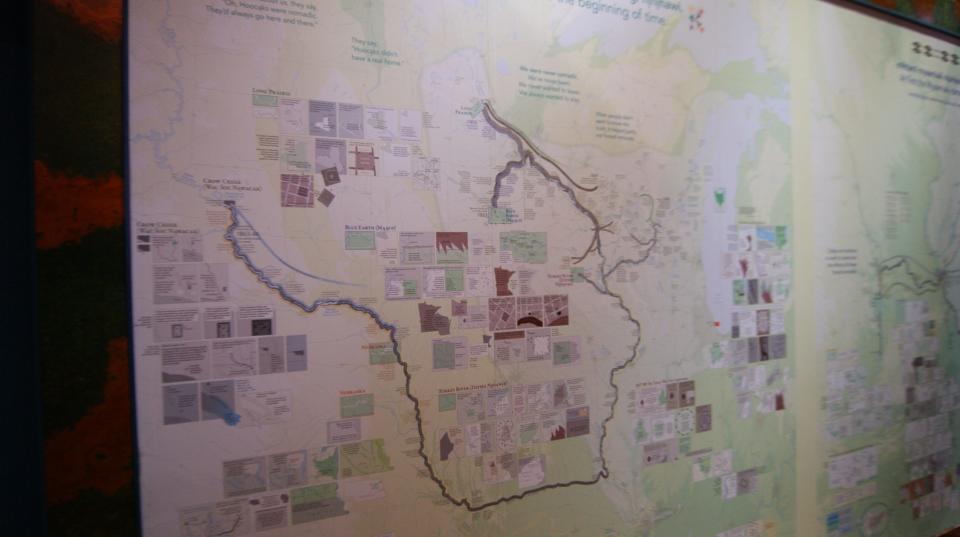

Ho-Chunk tribal historians contributed a large map display for the exhibit that shows migration and forced relocation of several tribes in the Midwest.

Dorothy Ramirez, a Ho-Chunk Nation citizen, previewed the exhibit before it opened to the public and was intrigued by the Ho-Chunk display, which included a piece of her own family history.

She said she wasn’t aware of her grandfather’s experience in a boarding school until she saw the display about that.

The boarding schools were designed by the federal government and the Catholic Church to forcefully assimilate Indigenous children, such as by discouraging their cultural traditions and use of their language.

Ramirez said her grandfather, Nathaniel Cloud, still speaks Ho-Chunk fluently.

Frank Vaisvilas is a Report For America corps member based at the Green Bay Press-Gazette covering Native American issues in Wisconsin. He can be reached at 920-228-0437 or fvaisvilas@gannett.com, or on Twitter at @vaisvilas_frank. Please consider supporting journalism that informs our democracy with a tax-deductible gift to this reporting effort at GreenBayPressGazette.com/RFA.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Indigenous nations in Wisconsin featured at Field Museum in Chicago