Indigenous snowmobile expedition wraps near Quebec City. Participants call it an exercise of healing

Last year Michèle Audette was watching the first edition of the First Nations Expedition online, but this year the senator cheered on about 50 snowmobilers in person as they rolled into Site Meshkenu located in Saint-Tite-des-Caps, just north of Quebec City.

Saturday marked the end of a 15-day, 3,230-kilometre expedition focused on reconciliation and healing.

The first edition of the trip held last March was created to raise awareness of three main issues — the plight of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, children who never came home from residential schools and the climate of racism that had claimed the lives of Indigenous people, including Joyce Echaquan.

Echaquan died in a Joliette hospital in 2020 after video showed health-care staff hurling racist remarks at her. Her death, and the footage leading up to it, sparked outrage and activism, especially after a Quebec coroner reported that if Echaquan had been white, she would still be alive.

Audette, Innu from Uashat mak Mani-Utenam, says it was a pleasant surprise to hear more non-Indigenous people talking about the expedition this year. She hopes they'll understand its significance.

"I was proud," said Audette, standing among dozens of families and friends bundled up and waiting to catch a glimpse of the headlights of the snowmobiles. "I said 'beautiful things [warrant] beautiful reactions.'"

Nathalie Guay, co-director for MAMUK, a multi-service centre in Quebec City for Indigenous peoples, had spent the week preparing for the expedition's final stop.

Michèle Audette says more non-Indigenous people were aware of the snowmobile expedition this year. (Rachel Watts/CBC)

Guay and her mother, Pénélope Guay, worked to get Site Meshkenu ready for 40 plus visitors to stay overnight.

Pénélope says it's about much more than just a celebration.

"Yes, it's a meal, but it's also a time to pause," said Pénélope. "It's really a healing process that we wanted to finish."

For participant, Dave Robichaud-Condo, he thought about the survivors he met throughout the snowmobile trip.

Aboard his snowmobile for nearly 10 hours a day for two weeks, Robichaud-Condo, Mi'kmaq from Gesgapegiag First Nation on the Gaspé Coast, says the expedition gave him an opportunity to put himself in the shoes of those who suffered in residential schools, or lost family as a result of systemic racism.

"I'm like realizing, imagine if it would happen to me," said Robichaud-Condo.

"I was like almost like in shock because before I was just watching documentaries about them like on TV. But when you're like one-on-one with the person … you're like wow."

Although the team experienced extreme temperatures, thaws and mechanical challenges as part of their journey, Robichaud-Condo says their mission was accomplished.

Dave Robichaud-Condo reunited with his wife and kids when he arrived by snowmobile. (Rachel Watts/CBC)

'I needed this,' says non-Indigenous participant

The expedition kicked off on the Innu First Nation of Pessamit, Que., on the North Shore on Jan. 27.

This year, organizers say healing and reconciliation were still top of mind, but they had a fourth goal — to involve non-Indigenous participants.

Victor Hamel was one of them. He says this trip was emotional.

"I needed this," said Hamel, who is from Baie-Comeau, Que. "There's [been] a lot of sharing. I made some very, very good friends. It's almost like a family now after two weeks."

Drummers flank the snowmobile trail, preparing for the arrival of the participants. (Rachel Watts/CBC)

He says it's important for everyone to be educated about the reality Indigenous peoples continue to face.

"They've had a lot of suffering to go through," said Hamel. "You can't remain insensitive to these things …I think it's important that things improve."

Hamel, whose children are Indigenous, says he's not sure a third edition will take place next year. He says organizers might need time to rest and reset.

Partnership with Federation of Quebec Snowmobile Clubs

This year the expedition partnered with the Federation of Quebec Snowmobile Clubs to use their trails.

Victor Hamel says spending upwards of two weeks with fellow participants has made the team feel more like a family. (Rachel Watts/CBC)

The head of the federation, Stephane Desroches, says he's proud to contribute.

"We need to rebuild that relationship because a lot has been broken [with] what happened between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. I think on our side it was a nice token of appreciation to be able to share with them," said Desroches.

He says nearly half of the trails are on ancestral Indigenous land. This year's edition posed unique challenges due to weather.

"Great mother nature didn't help us," said Desroches.

"It must have been difficult for them … [They] couldn't even ride at a good cruising speed."

Billy Shecanapish draped his snowmobile with the Kawawachikamach flag as he rode past the finish line. (Rachel Watts/CBC)

Over 300 people wanted to take part

Harry Sharl says at one point there was no snow and the team had to travel on gravel or paved roads for over 100 kilometres.

Sharl, who was part of the support crew for the team and who helped transport participant's luggage on trailers, says interest in this year's event peaked.

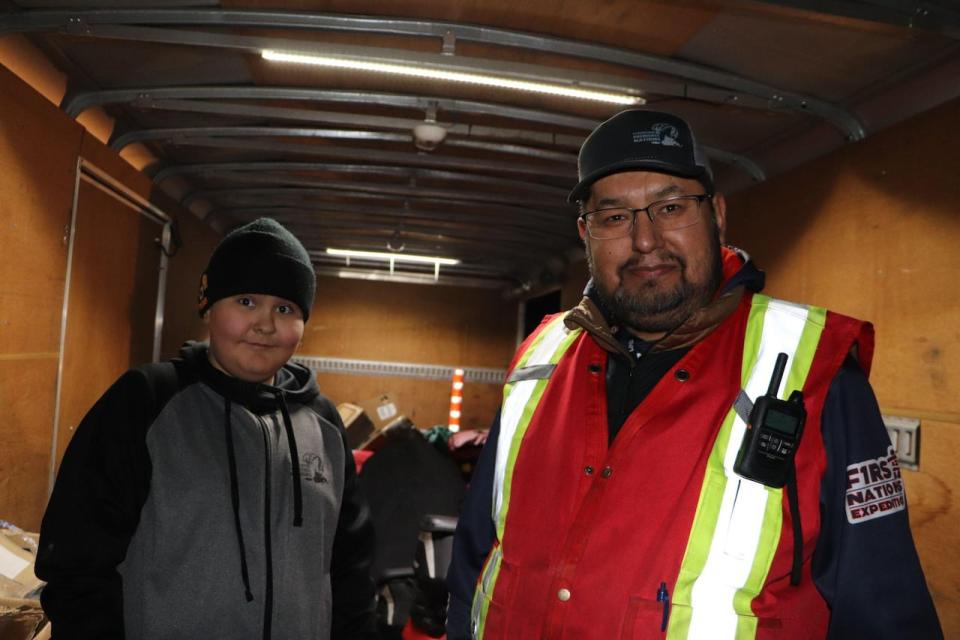

Harry Sharl and his step-son, Myles Fontaine, unloaded a trailer full of participant's luggage. (Rachel Watts/CBC)

"There were over 300 participants that submitted the request to be a part. So they only took about 50," explained Sharl.

He says half of the participants this year were Indigenous and the other half non-Indigenous.

Robichaud-Condo says having non-Indigenous participants allowed for cultural exchanges throughout the trip.

At one of the healing circles, Robichaud-Condo says a non-Indigenous participant shared that he was ashamed of the ways in which Indigenous peoples were discriminated against.

"He said 'You guys don't deserve that,''' said Robichaud-Condo. "It was like more bonding between everybody in the group … I think in 2024, we have to join ourselves together."

Pascale Bacon-Picard, one of the expedition's participants, was welcomed at the finish line by her family. (Rachel Watts/CBC)