'Indigenuity' in Sustainability—a Beginning

Guest Opinion. Let us start at the beginning. Before there were “Land Acknowledgments,” as written pledges of recognition of the first Earth-Keepers living in North America, Indigenous Peoples of this land, now known as the United States of America, had lifeways that embodied respect for the land.

Yes, they offered invocations, prayers, blessings, thanksgivings, and ceremonial traditions of gratitude. However, the need to acknowledge the importance of the land, air, water, and the life surrounding them came quite naturally to humans who understood themselves as a part of the natural world, who understood they lived among kinfolk—different-than-human persons—in communities inclusive of plant and animal relatives. Tribal languages, customs, habits, clan systems, social organization, and totems speak volumes about these relationships.

For my Tsoyaha or Yuchi People, removal from our homelands nearly two hundred years ago through the depredations of US policy constituted a climate change event. The climate change the Tsoyaha experienced with our removal from Georgia to what is now Northeastern Oklahoma was not nearly as extreme as what the more than twenty-five tribal nations experienced who were removed from their homes in the Northeast US and Great Lakes region to lands in what is now eastern Kansas. Let’s be clear: there was no Trail of Tears. There were Trails of Tears—dozens of them. Yes, climate change and the struggle for cultural survival is something many tribes understand. It is not an exaggeration to suggest that with respect to covenants and Original Instructions the requirement to continue ancient ceremonies and traditional cultural practices was difficult.

The institutional forces of cultural assimilation laid on top of a removal from homelands was traumatic and posed the first test of Indigenuity—the application of ancient knowledge and wisdom to solve new problems. Suffice it to say, the resilience of tribes in the face of nothing less than a cultural dismemberment process is a testimony to tribal resilience and practical exercises of Indigenuity. In the face of, in many cases, already present traumas, removal to new lands required renewal of Original Instructions in principle: commitments to maintain good relations even in these new lands where Peoples found themselves. I leave it to Indigenous tribal historians to tell their stories of what this meant, but the fact that old and new “medicines” were found speaks to the foundation of Indigenuity—the ability to work with place, to find new relatives in the surrounding life—to maintain Original Instructions even in new places.

Nevertheless, the beginning of ancient practices of Indigenuity come from the deep experiential aspects of Indigenous lifeways: a sense of place—a unique cultural relatedness to a particular landscape or seascape. This awareness can be found across North America and, indeed, in many places around the world among Indigenous Peoples. Indigenuity has an ancient genealogy, for with every generation something appears in the living world that presents an opportunity, a challenge, to apply the wisdom of their ancestors to address changing situations in the places they call home. And, for the past two hundred years, sometimes this has happened in places different from their ancestral homeland, given federal government policies of removal and relocation.

To my knowledge, the English word conveying Indigenous ingenuity—Indigenuity—has only been around since the early 2000s. The word emerged at Haskell Indian Nations University out of discussions my colleagues and students were having around 2002 or 2003. Of course, the idea of Indigenuity was presciently contained in the written works of major Indigenous thinkers a half-century ago. I take no credit for the word or the idea and activities it embodies. In an existential and experiential sense, it—Indigenuity—resides in respectful kinship relationships with the world in which we live. Naturally, our Indigenous histories begin with our fundamental relationship to the land, water, and, in my Tsoyaha traditions, the sun.

Vine Deloria, Jr. famously observed in his 1973 book, God Is Red, “American Indians hold their lands—their places, as having the highest possible meaning and all their statements are made with that reference point in mind.” Deloria identified one of the distinguishing features separating Western and Indigenous thinkers as the Western idea of history unfolding in a temporal linear sense, while American Indians think of history spatially: as a particular place and their relationship with the power residing in that place. Deloria understood that Western Peoples have seen themselves at the front of the line, leading the way, in an overwhelmingly positive progressive historical unfolding of their activities. American Indians understand their identities, as Peoples, as emergent from the symbiotic relationship between themselves and the place they consider their homeland.

At a fundamental level, Indigenuity is about imagination and creativity rooted in a People’s deep spatial and experiential relationship to the land, air, and water, and the life found therein.

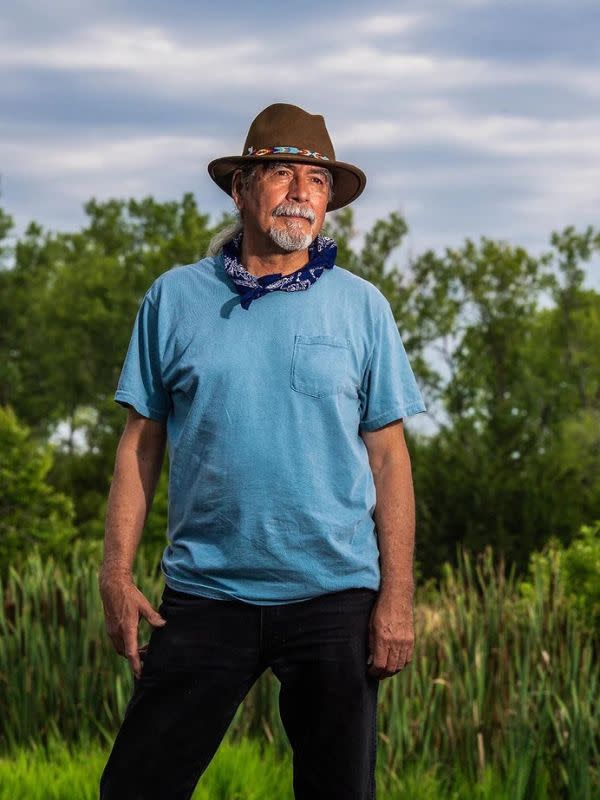

Daniel Wildcat’s forthcoming book On Indigenuity: Learning the Lessons of Mother Earth will be available from Fulcrum Publishing on November 14th. In the book, Wildcat explores the ways in which humankind must utilize the traditions, thought processes, and wisdom of Native Peoples if we are to address climate change and quell a continually warming planet. The book is available for preorder here.

About the Author: "Elyse Wild is senior editor for Native News Online and Tribal Business News. "

Contact: ewild@indiancountrymedia.com