The Indy 500 Needs More Cheating

This Sunday, the 103rd Indianapolis 500 will be contested by 33 nearly identical cars. It's a derby of conventional wisdom vs. wise conventionality, combined with restrictive rules and mandated equipment. In many ways, that's for the good; it maximizes the role of both driver talent and pure luck. But I miss the cheating.

Cheating not in the sense of breaking the rules, but in undermining them. Finding a loophole and keeping the nefarious plans quiet until the moment it's sprung upon the unsuspecting competition, after it's too late for them to do anything about it. Something so sneaky and underhanded that, even going in, you know it's going to be banned immediately after the race. And 25 years ago, Roger Penske, Mercedes-Benz, and Ilmor Engineering found and exploited the most gaping loophole in the history of the race.

It was, of course, the infamous purpose-built Mercedes-Ilmor 500I pushrod V-8 engine that dominated the 1994 Indianapolis 500. It was 3.4 liters of pure race engine that took advantage of USAC rules intended to encourage the use of production-based pushrod, overhead valve engines-engines like the Buick V-6s that John Menard's teams campaigned with awesome futility in the mid-1980s.

The rules allowed such engines up to a monstrous 55 inches of turbocharger boost instead of the 45 allowed for DOHC multivalve race motors. But there had been a little-noticed rule change in 1991 that removed any production-based requirement. In utter secrecy, the full drivetrain package was developed during 1993 at Ilmor in England and clandestinely in a Penske Truck Rental facility down the street from the race shop in Reading, Pennsylvania.

It was a small skunkworks-style group that kept secrets well. "We flew parts back and forth," current Penske team manager John Bouslog told Autosport in 2017. "A lot of times, we bought seats on the Concorde to get pistons and other engine parts to the shop from England." It was Penske's competitive drive expressed in audacity, engineering prowess, and logistics. "The development curve was steep. The engine became common knowledge once we had to go into production mode and build those engines for Indianapolis, and that is when everyone got involved."

Kevin Wilson, whose current responsibilities include editing this column for Car and Driver, was at the debut of Penske's PC-23 equipped with the 500I. He recalls the shocked reaction of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway president, who was observing the event in the speedway museum: "I watched Tony George's face fall as he realized what he was seeing."

The PC-23 was already a proven winner in CART IndyCar competition, where it ran Ilmor's formerly Chevrolet-branded 2.7-liter DOHC 32-valve V-8. Before getting to Indy, Emerson Fittipaldi used his to win at Phoenix, and Al Unser, Jr., took the Long Beach Grand Prix. While Fittipaldi would only grab that one win, Unser would win eight times during the 1994 season and Paul Tracy another three. That's 12 of the 16 races that season won by the PC-23 which, even without Indy pushrod success that year, would still be one of the greatest open-wheel race cars ever in American competition.

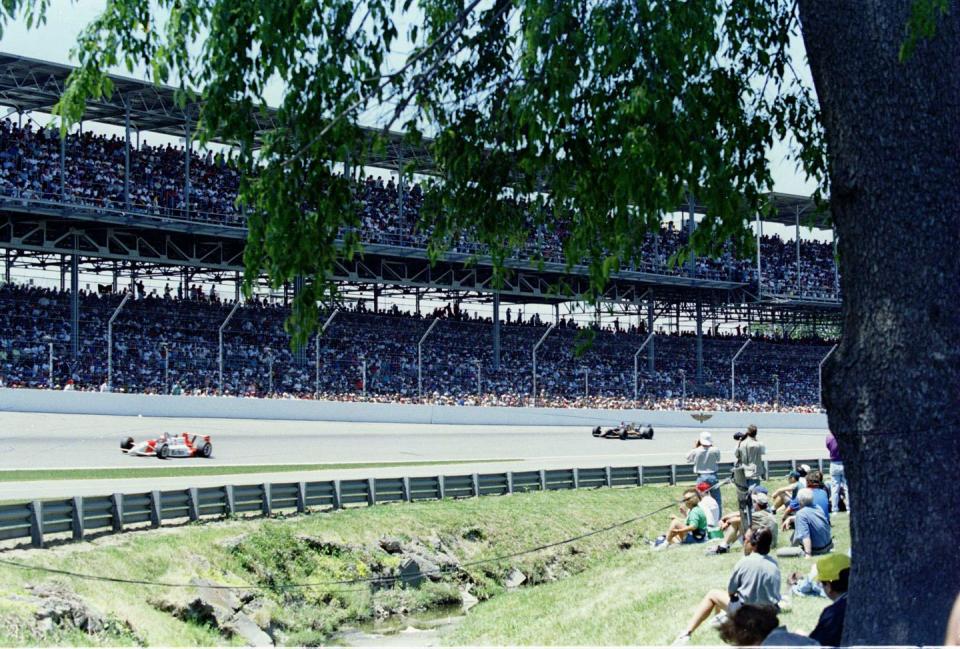

With a 200- to 300-hp advantage over the rest of the field (more than 1000 horsepower in all), the combination of PC-23 and 500I was clearly dominant at the Speedway. Unser, Jr., put his on the pole at 228.011 mph. A quarter-century later, that speed would have had him qualifying 19th for the 2019 race.

But it was Fittipaldi, starting with Unser on the front row, who dominated the race. He led 145 of the 200 laps, and by lap 157 the only two cars on the lead lap were Fittipaldi and Unser. And on lap 180, Fittipaldi had lapped Unser, too. Unser got his lap back on 183 and was just forward of Fittipaldi when the Brazilian driver went too low, nudged into the rumble strips at the bottom of the track, got loose, and slid up into the wall on lap 185. That handed the race to Unser.

Penske and Ilmor spent a lot of Mercedes-Benz's money to build an engine that could compete only under USAC rules in the only USAC-sanctioned IndyCar race, the Indianapolis 500. And they did it knowing full well that the engine would likely be banned after dominating the Memorial Day classic. That's exactly what happened. The 500I has never appeared in competition again.

It's pushing it to call what Penske and Ilmor did in 1994 "cheating." But it's awfully close. It's also the sort of envelope-pushing, rules-stretching, risk-taking arrogant adventure that makes a great story.

A great story that's practically impossible today.

All professional sports are about telling great stories. It's the 1927 Yankees with the "Murderers' Row" lineup headed by Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. It's the Magic vs. Bird rivalry that salvaged the NBA during the 1980s. It's Chrysler's 426 Hemi, so dominant during the 1964 NASCAR season that it was banned for 1965. It's the 1970 Chapparal 2J that used a snowmobile motor-driven fan to suck itself to the ground, so quick in the Can Am that it was banned. It's a million legends about Smokey Yunick.

Cheating-or near cheating or whatever-isn't something you teach your kids as a moral virtue. It's not always successful, either. But it makes for great stories, and that's something that's missing in racing today.

Whatever happens at Indy on Sunday, it would've been more interesting if someone had been cheating.

Okay, it's a push to call the 500I a cheat. But I'm not above cheating to come up with a column title that will make you read it.

('You Might Also Like',)