IndyStar sports director Jenny Green retires: 'Nothing hurts like this'

INDIANAPOLIS ‒ Jenny Green is sitting on the back porch of her Indianapolis home in a navy blue IndyStar sports polo shirt and jeans, sitting on a wicker chair where she can see chipmunks and squirrels scurrying past in the yard.

She is sitting at her Delaware Street home and, more often than not, she is staring down at her feet.

Green is humble. Praise makes her blush. She hates attention. She likes nothing better than to be behind the scenes making things happen, making things better.

That, after all, has been her life as editor extraordinaire, doing all the stuff that makes a story great, a story brilliant, and doing it with little credit. Editors don't get bylines and Green has always liked that.

Truth be told, Green doesn't want to be doing this, either. Being interviewed for a story on her retirement after an illustrious 35-year career of intense, high pressure journalism, helping to churn out newspapers in major metropolitan markets across the United States, her last 20 years at the Indianapolis Star.

Green, 58, retired from her role as IndyStar’s sports director Sept. 1 due to health issues.

Five days later, she is reluctantly telling her story, one of a humble upbringing that shaped her into a woman who, by 23, was the news director at her first paper. Who, by 28, was third in charge at the Cincinnati Enquirer. And who, in her early 30s, was leading the Broward County edition of the Miami Herald.

Green never got the chance to not be in charge. Everywhere she went, people saw something in her, something that said this woman needs to be a leader. Green had a gentle, calming spirit across the newsroom, IndyStar executive editor Bro Krift said.

“She earned her peers’ respect because of her dedication to the craft as well as her devotion to those she worked beside," Krift wrote in an email announcing Green's retirement. "She cared about you and me and everyone who came into this newsroom."

Green's departure from journalism leaves behind a portfolio that brought readers some of the biggest stories to make headlines in the U.S.

The first Black president, Barack Obama, in 2008. The tragedy of Sept. 11, 2001, that changed the landscape of America. The contentious "hanging chad" 2000 election between George Bush and Al Gore in Broward County. Elian Gonzalez, the 5-year-old boy found on Thanksgiving Day 1999 off the coast of Florida clinging to an innertube as his mother died trying to bring her family to the U.S. from Cuba.

In Indianapolis, Green was there for Andrew Luck's abrupt retirement in 2019, the Pacers-Pistons brawl in 2004, the Hamilton Avenue murders that left three children and four adults dead in an Indianapolis home. And she was there in 2006 for the accident that killed five Taylor University students and ended in the mistaken identification of two victims.

Green was there, too, for Qudrat Wardak, the baby with a bad heart who came to Indianapolis from a squalid Afghan refugee camp. He received his new heart in February 2005, a beacon of joy and hope, then he died three months later.

Jenny Morlan will never forget that little boy’s death because of the devastation, but also because of Green’s heart and compassion.

Green was IndyStar’s front page editor that night in 2005, when she was called over by another editor in the newsroom and told Qudrat had died. Green walked back to her desk, sat down and cried.

"She could barely get out the words, 'Qudrat died,’” said Morlan, a former IndyStar editor who sat across from Green in the newsroom. “I will never forget that, how much she cared about the people her newspaper wrote about.”

And how much she cared about the people in the newsroom. Green would never ask anyone to do anything she wouldn't do herself.

Morlan says if a newsroom were a restaurant and, to run smoothly, that restaurant needed the dishes washed, Green would wash the dishes.

As big stories broke, Green would not only edit but pitch in to write sidebars and stories, never putting her byline on them. Just writing to make things better.

Green loved journalism. She still loves journalism.

“If I could have stayed,” Green said from her home last week. “I would have.”

'She had this presence'

Green is the daughter of artists, a father and mother who sometimes were starving artists. She was a kid in Kansas who, one winter, lived in a tiny one-room studio no bigger than a sun porch with her parents and two brothers. She was a young girl who, in that brutal winter, trudged into the dark, frigid snow to use the outhouse.

She was a student who qualified for free school lunches until her mom, Donna Barker, realized that the kids who got free lunches had different colored cards than the children whose families paid for lunch.

Donna and Ed Barker sent in the money to make sure Green and her two brothers had the cards that would keep other kids from teasing them.

As a young girl, Green tagged along with her parents as they drove from city to city for art shows, her mom a sculptor and her dad a potter.

Her dad, Ed Barker, always said: "It's no way to make a living, but it's a great life."

Green didn't dream of being a journalist. That wasn’t something a young girl living in remote Kansas in the 1970s dreamed of. But after graduating from high school, Green went to the University of Kansas, where she enrolled in a copy editing class, and loved it. Then she enrolled in more journalism classes and loved those even more.

She started working for the university’s newspaper and knew this would be her career. When she graduated college, Green didn’t have to search for a job. Her first professor took care of that.

“He fell for Jenny,” said her husband, Ted Green. “He saw something there.”

Green was hired as a copy editor at the Argus Leader in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. But soon, the newspaper saw what her professor had seen. At 23, she was named the paper’s news editor.

Fifteen months later, Green landed a spot at the Cincinnati Enquirer as a copy editor then wire editor, then assistant news editor. And then she became news editor, third in charge at the paper.

That’s when Ted Green met his future wife.

Ted Green was working in Boca Raton and had been out in the sun playing beach volleyball. He was interviewing for the Enquirer’s sports copy desk in the early 1990s. He went to a news meeting surrounded by people, mostly in their 40s and 50s, mostly men.

“And at the far end was this beautiful, 28-year-old news editor, I mean striking,” Ted Green said. When he was introduced at that meeting, Green called him “Tan Ted.” He was hooked.

He watched Green go around the table asking what stories were coming the next day, local, national, what would run on the front page. “Man, she was leading this meeting, a woman in her 20s,” Ted Green said. “She had this presence.”

When he was hired by the Enquirer, Ted Green continued to watch in awe this young woman who, virtually, ran the newsroom. At night, the journalists would go out to the bar after work. Green and Ted ended up at the same bar on more than one occasion. They fell in love and were married in 1994.

Two years later, both got impressive job offers and “Tan Ted” and Green were headed toward the sun.

'You want to make her proud of you'

In the spring of 1996, the Greens made a new home in Florida working for the Miami Herald. They lived in Hollywood, close to where Green headed the copy desk of the Broward County edition of the newspaper. Ted Green worked in the main newsroom as an assistant sports editor.

Green’s passion to give readers her best, her newsroom’s best, went to new levels.

When a hurricane ended in tragedy in Broward County, a family electrocuted as they tried to save one another walking into waters with downed lines, as people drove off into canals thinking they were on the road, Green and colleague Mary Byrne wanted to make sure those deaths weren't buried.

They wanted to be sure they were on the front page of the Broward County edition. Green and Byrne drove down I-95, fighting flooding, and pulled into a parking garage by the Miami Herald's main office. They rolled up their jeans and waded into the newsroom.

And they changed the front page of the Broward edition.

"They were so concerned that the Broward news get that coverage, they risked a lot," said Ted Green. "They did this on their own. That was their commitment to their readers."

Paul Anger was there for all of that. He hired Green at the Miami Herald and watched as Green led a copy desk in a Broward newsroom of 100 people.

"She was one of the most calm, pragmatic, organized editors that I had ever worked with," said Anger. "I remember thinking that she is unusual in this business. There isn't a lot of drama; there isn't a lot of hand wringing."

Green never needed to raise her voice. Though, she said there was one night in Cincinnati that she yelled across the newsroom when a reporter hadn't closed a file and deadlines were looming.

"So I did that once," Green said, laughing. "One time."

But mostly, Green never yelled. She didn't have to. "People wanted to do well not just for themselves but for her," said Anger. "You wanted to make her proud of you."

Green was brilliant and unbelievably competent, said Rick Hirsch, who led the Broward County office during Green's tenure and is now the senior editor for talent development at McClatchy.

"In some ways, she was too nice to be a journalist," he said. "She was really kind and level-headed and had great news judgment. She was really just a consummate pro and a delight and had a sense of humor and didn't take herself too seriously. When you put all that together, how many journalists do you know that check all those boxes?"

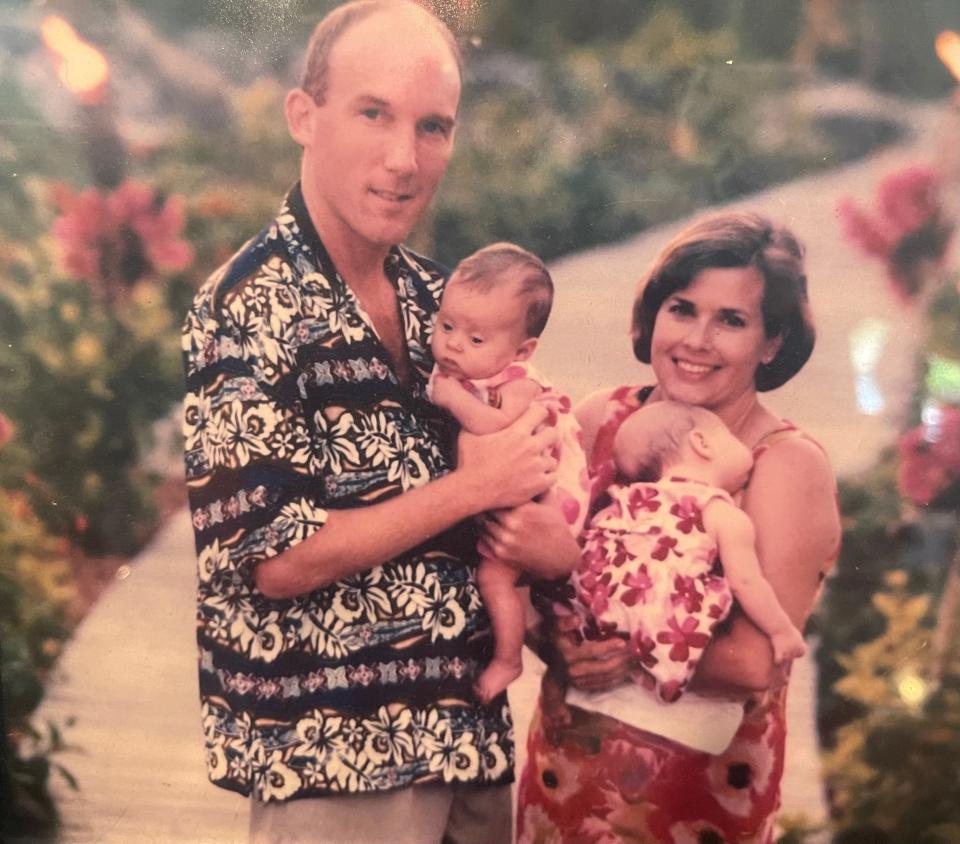

Green shined at the Herald and so did Ted Green. Soon, both got dream job offers ‒ Green to be national editor of USA Today and Ted Green to be assistant sports editor at the Washington Post. It was perfect. It would have been perfect, but Green was pregnant with twin girls. They didn’t want to put undue stress on her pregnancy.

After her daughters were born, Green got another call, this time from the Indianapolis Star. The paper wanted her. She and Ted agreed the Midwest would be a great place to raise their children.

They packed up 6-month-old Anna and Dylan, three cats and their life in a U-Haul and towed a station wagon to Indianapolis. Green went on to rise through the ranks of the IndyStar.

"It's really not surprising to me at all that she has succeeded so well being in Indy," said Anger. "What she's done there, you could really see it coming."

'The heart of the Star for 20 years'

For the past 20 years at the Indianapolis Star, Green has been a part of every aspect of the newsroom. And she has done it modestly, compassionately, earning the respect of all who cross her path.

"I’ve never seen her angry or say an unkind word about anyone," said Kim Mitchell, administrative manager, news operations. "(She is) quick to offer help with the most mundane things. She is humble, soft spoken and will give you the last $20 in her wallet. Then will ask if you need more money."

After Green's retirement was announced, IndyStar sports columnist Gregg Doyel wrote an email to the newsroom.

"If you’ve never worked with Jenny, you’d have no idea how wonderful she is because she won’t tell you or even carry herself in a way that suggests she’s special," he wrote. "She is special. Her manner is just one reason. Her brilliance as a word editor is another. Her gentle form of leadership is another. Jenny is the best sports editor I’ve ever worked for, and there have been many, and she’s the best by a wide margin … nothing hurts like this."

Universally respected, that's how Morlan describes Green, "respected by the highest boss and by the intern in the newsroom."

"She would accomplish more just by staying still," said Ted Green. "And she also inspired incredible confidence in all of the editors and all of the writers. I think she has been the heart of the Star for 20 years."

The heart that no one ever heard beating.

"I’ve never worked with anyone less interested in credit than Jenny," said Nat Newell, deputy sports editor, who is IndyStar's interim sports director. "So it can be hard to understand how big a part of our success she was."

But more than the successes, more than anything, was Green's leadership style.

“Here’s the thing that I remember about Jenny and it's more of a feeling than a series of anecdotes," said Anger. "You know what they say? You don't remember everything about somebody, but you remember how they made you feel. She made you feel special."

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @DanaBenbow. Reach her via email: dbenbow@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: IndyStar sports director Jenny Green retires after 35 years in news