Inflation, mental health, jobs. Why are U.S parents so stressed?

Editor’s note: This story is based on data from the 2023 American Family Survey.

American adults believe the cost associated with raising a family is the biggest challenge facing American families overall, with concerns about technology, including social media and video games, tied with “high work demands and parental stress” for second place.

Having money to meet inflation’s demands and affording family life is a real concern for many U.S. households, according to the ninth annual American Family Survey, released Tuesday at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C. The report says the economy has largely recovered from COVID-19’s challenges — in part due to government support. But it adds, “The public also remains deeply worried about inflation, particularly if they have suffered recent crises or lack of income.”

The survey, which included a nationally representative sample of 3,000 adults, presented a curated list of 15 challenges and asked half to consider their own families, the other half to consider families in general. Each person could choose three challenges.

Related

Children growing up without two parents at home and mental and physical health struggles round out the top five in the curated list. Those choices far surpassed violence and abuse in families, lack of education opportunities, sexual permissiveness, drugs and alcohol, and crime and other threats to safety. Those were each chosen by no more than 1 in 8 respondents.

In the middle for U.S. families were declining religious faith and church attendance, lack of good jobs or wages, difficulty finding quality family time, parents’ lack of commitment to each other and tension or disagreements in families.

The survey examines the actions, attitudes and opinions of U.S. adults on topics from what families do together and the strength of marriage to how families struggle, what policies might help and thoughts on issues like abortion and declining fertility. Conducted by YouGov for Brigham Young University’s Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy, the Wheatley Institute at BYU and the Deseret News, it has an error margin of +/- 2.1 percentage points and was fielded Aug. 3-15.

The report separates what people think about their own families from “The Family” as an institution. And the news is pretty good when Americans ponder their own: More than three-fourths of adults express satisfaction with their families, compared to 11% who express dissatisfaction.

Across political lines, top concerns about their own families are mental or physical health and finding enough family time. “Physical and mental health are probably more of a problem for people than our data had previously shown,” said study co-investigator and report co-author Jeremy C. Pope, who shares both titles with Christopher F. Karpowitz. Both are BYU political science professors.

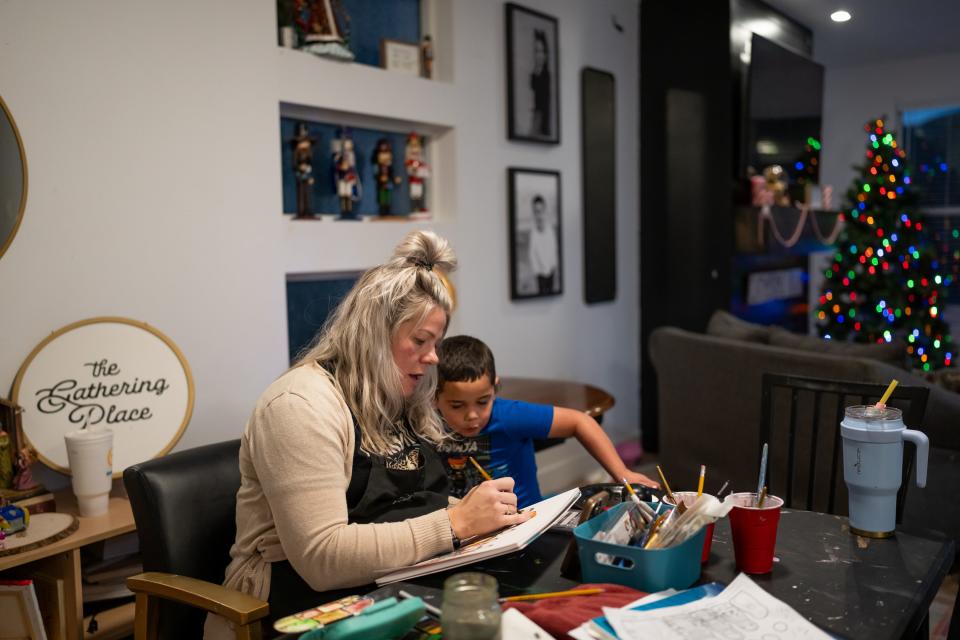

Jessica and Makafana Palu met in his native Tonga, where he worked at the school where she was teaching art. The Eagle Mountain couple married eight years ago. They are deeply religious and each served missions for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. She said they want to pass that faith to their kids, along with a heart for serving others.

They are not surprised that money is a huge challenge for families. They have four very young children — daughters Fine, 7, and Melolini, 5, as well as sons Akilisi, 4, and Joseph, 3. They are expecting a tie-breaker that will give the boys an edge in about a week. They plan to call baby Makafana “Rocky.”

Jessica Palu said the past year has been among the hardest her family has faced financially. Her husband had a long, terrible bout with COVID-19 and recovered slowly after being hospitalized. He nearly died. He couldn’t work for months, nor was he able to return to the rigorous job he’d had.

This year, he started his own business, doing concrete work and landscaping, which he’d done as a side job. They’re hoping 2024 is a little easier on finances. But she has learned, she said, that neighbors and friends can be awesome in a crisis.

Mental health across ages

Despite similarities in individual families, political divisions loom large in attitudes about families in general.

Asked about challenges facing teens, parents of teens believe mental health, including suicidality, and technology overuse are the biggest issues. On the right, the two are seen as intertwined.

For teens, Democrats were more worried than Republicans about pressure to succeed, mental health, difficult relationships with family members and navigating sexual identity. Republicans worried more than Democrats about teens’ overuse of technology, poor-quality schools, family breakdown and sexual activity decisions. There wasn’t much partisan difference on bullying, friendships and peer relationships, pressure to use drugs or alcohol, abuse, safety in communities, too few good work opportunities and availability of pornography.

The report emphasizes that not ranking as high does not indicate lack of concern. For instance, teen mental health was No. 2 on Republican parents’ concerns, but was chosen by a larger share of Democrats.

Psychotherapist Jonathan Berent, author of “Social Anxiety” and other books, calls social anxiety and related problems “entrenched as the social disorder of our time.” At least 1 in 8 people have it, he said, and “it’s very misunderstood.”

Youths have never struggled with mental health more than they do now, per Berent, who notes substance use disorder is also very high. For most who struggle, he said the solution offered is often medication, without figuring out root causes — “a lot of band-aiding.”

Related

Richard Petts, professor of sociology at Ball State University, sees a “pervasive” mental health problem as a growing number of people deal with challenges amid inadequate resources. He said universities are backed up when it comes to providing mental health appointments for college students, who often turn to professors and others who may not be qualified to help.

Many blame social media for a rise in mental health issues, particularly among the young. Petts said there are also other factors. “We’ve dealt with a lot as a society, one disaster after another: COVID. Economic downturns. Wars. Mass shootings.” Even efforts to forestall bad things could contribute. He wonders what school lockdown drills do to mental health.

“It shouldn’t be a surprise that people are struggling,” said Petts, noting how pressured parents are to get kids in activities to help earn a spot in the best schools, how early college prep starts and worries about paying for things, including education.

Shawn Fremstad, director of Law and Political Economy and senior adviser at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, agrees, citing “a lot of insecurity, a lot of change in a tumultuous period. I think of it almost as more insecurity and uncertainty about things, as opposed to pure struggle,” he said.

Partisan differences

The view of “The Family” is largely partisan, the survey found. For example, support for marriage as a path to stable, committed relationships is falling among those on the left, where Democrats see as top challenges parental stress and the cost of raising a family. On the right, concern is greatest about single parenting and a decline in religious faith.

But there’s also remarkably little difference in how happy people are in their own families — or in how they live. The survey found “far more agreement than disagreement across party, religion and income” when pondering personal family challenges.

Work and money

There were also no partisan differences in concerns about high work demands and parental stress for “your family,” but asked about families overall, Democrats were more concerned than Republicans.

If you’re worrying about the economy, workplace productivity comes to mind, said Michelle Janning, sociology professor and chair of social science at Whitman College. She’s been pondering COVID-19’s impact and remote work. “I think we are seeing an interesting paradox emerging, especially for working mothers,” she said.

Bosses are trying to figure out how to balance the advantages of remote work against the need for face-to-face work, in part to create workplace culture. Parents say they have more control over time and place with remote work and it’s easier to shift the schedule. And some bosses don’t mind, if work gets done on time.

Meanwhile, she said, when there’s fluidity and autonomy, “a workplace can get greedy” and begin to overcompensate and over-monitor. Some bosses wonder if remote workers are committed enough or get too distracted.

Economic inequality may come into play. People who work from home need space and tools to do it well, said Janning.

While inflation and the economy are widespread concerns, those at the lower end of the economic scale are hardest hit. Half of Americans with an income below $40,000 a year are experiencing an economic crisis, the survey found. About 4 in 10 of those making more than $100,000 also worry about inflation. Crises don’t care about party politics, either, impacting people of different ideologies at about the same rate.

“In the everyday lives of families, costs are the issue,” said Karpowitz. “It’s not as much finding a job as being able to afford things even if you have a job.” That’s a worry for middle- and low-income people, while it’s less worrisome at upper-level income distributions, but even some of them are stressed.

Cost of children

According to the report, most economic indicators have recovered from the shock of the pandemic. “Counterintuitively, however, personal economic crises are on the rise — perhaps because of reduced government income support.”

Fewer than a quarter of the adults polled said raising children is “affordable” for most families. Fifty-nine percent directly disagreed that it’s affordable.

Pope said the government helped families a lot during COVID-19. “Some of it may have been misguided, but a lot of it hit its target and made it so families had enough money to weather those crises. That has dried up in the last year and now people are having as many crises as they used to, more or less.”

What if the economy gets worse? he wonders. “We’re in a kind of complicated economy at the moment — pretty decent in many ways, but inflation lingers.”

While other families not disciplining their children is a perennial top concern in the survey, financial and related worries showed up in many forms, not just costs associated with raising a family. Nearly a third said high work demands and parental stress vex families. Lack of government programs to support families was cited by 14%, while 11% listed lack of good jobs.

Belgrade, Montana, mom Melanie Musson is acutely aware of rising prices, she said by email. She has “five wildly wonderful kids at home,” ages 3, 5, 7, 11 and 13. But she and her husband bought their home less than two years ago and they’re still getting used to the higher payment and the higher costs of electricity, taxes and insurance.

“The extra space is worth it,” she said, “But budgeting is a little more stressful.”

Musson said her worries include her kids and their health. She sees stories of accidents and illnesses online every day and “the fear that something could happen to our kids is real and can be heavy,” she said.

She knows they will face a lot of decisions as they grow. “One of my biggest goals for them is to be able to stand up for what’s right and not go with the flow just because it’s popular.”

She also worries about the impact artificial intelligence will have — and wishes it would just go away, despite any possible benefits.

Public policy for families

When it comes to family policy, there is very broad support for some policies, but also many partisan differences. And policy details would likely vary considerably depending on who drafted them and where eligibility lines were drawn.

Passing paid family leave would be helpful or very helpful, according to more than 86% of those polled, with more Democrats than Republicans saying “very helpful,” but clear majorities of both parties finding some benefit.

Child tax credits, Medicaid expansion for mothers, access to affordable housing, expanded access to mental health services for children and families and free or reduced-cost health care for children were all deemed at least helpful by more than 80% of those asked.

Just under 67% said student loan forgiveness would help family well-being, but there was a large partisan divide. Just over a quarter of Republicans said helpful or very helpful, compared to 89% of Democrats.

The report said that while conservatives believe marriage and stability are essential for families to thrive, “with a few exceptions, the right generally does not see a strong need to provide public support to families confronting economic trouble and vulnerability.”

“Maybe there’s a good case to be made that some of these policies would be counterproductive in some way we’re not seeing; policy can be complicated,” Pope said. “But there is a genuine hunger in the public for various policies to support families. I’m not here to argue for any set of policies. I’m just pointing out the public would like to see them implemented in many cases.”

Fremstad believes help given during the pandemic, including stimulus payments that spanned Trump and Biden administrations, has softened many views on providing some aid.

That doesn’t surprise Janning. “I think COVID afforded the world the chance to be better sociologists,” she said, providing “capacity to recognize that our circumstances are not just our own making, but the context in which family life is situated.”

Jennifer Randles is interim associate dean of the College of Social Sciences at California State University, Fresno, and wrote “Proposing Prosperity: Marriage Education Policy and Inequality in America.” She said the pandemic helped stabilize some families for a time, but now research says a lot of families are “worried about wipes and food and diapers and gas in the car to get to work.” Those struggling are not all working-poor families, but “working-class families earning just enough to not qualify for benefits but not enough to cover basic needs.”

“The pandemic demonstrated we all suffer amid big problems. We are all vulnerable to losing a job, to not having child care, to a health crisis. It helped to demonstrate that there is some common suffering all are vulnerable to way up the income spectrum, not just at the lowest levels,” said Cynthia Osborne, professor of early childhood education and policy and founder and executive director of the Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center at Vanderbilt University. “It also showed when we put resources toward problems, public policy can help in some ways.”

Karpowitz said the survey showed increases in the extent to which people didn’t pay a bill or skipped a meal, had to borrow money, moved in with someone or couldn’t see a doctor.

Despite partisan differences, he sees room to collaborate. “If Democrats were a little more vocal in support of the idea of marriage and commitment and Republicans were willing to be more generous, a coalition that would serve the needs of American families could form.”

While Karpowitz acknowledges that the political right and left likely have different ideas about how to implement policies, including means testing and work requirements, “that’s the stuff of politics. We’re just showing those are things that really do make a difference in the lives of families, and are a popular thing to do. There’s potential for Republicans and Democrats to come together. I think that’s going to need movement from both sides.”

Fremstad predicts the 2024 presidential election will come down to “who will address America’s insecurities the most, whatever they are. Some are economic.”

“I would say, by and large, the American family is doing better,” he said. “But it’s hard to talk about one American family because of class divides.”

Kids faced many struggles the past four years, Osborne said. Babies born in the pandemic had a delayed introduction to the world. Now 4-year-olds are trying to figure out how to act in a restaurant and there are kids in high school who never went to middle school.

“Those life transitions were really interrupted,” she said. “It’s going to take some time to settle back into some sense of normal, but kids don’t ever get a do-over. They don’t get to be 14 or 4 again,” she said.