‘If you’re innocent, he’ll walk you out the front gate.’ Kansas attorney was one of the good guys | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

More than a few of my heroes happen to be lawyers. Of course, those who protect our First Amendment rights wear capes and tights in my eyes. So do the kind of counselors who stand up for the hated and who, against ridiculous odds, manage on occasion to save the innocent from spending a lifetime behind bars. Some concentrate on correcting terrible wrongs, while others hold monsters to account.

Wichita defense attorney Richard Ney did a few of those things: He spent nearly 20 years as a public defender, was a national trainer on how to defend death penalty cases, and won the freedom of two wrongfully convicted clients I spoke to on Sunday. When he died last week, of pancreatic and kidney cancer, at age 69, Kansas lost one of the good guys.

“If it wasn’t for Richard, I have the distinct feeling I’d still be in prison right now,” said Chris Lyman, a former Army sergeant and Bronze Star recipient who spent nearly a decade in Ellsworth for killing his 8-month-old nephew, Johnathan Swann, who’d actually died of pneumonia.

It was an Ellsworth official, Lyman said, who first told him about Ney. “He said, ‘Richard Ney has walked 10 or 12 people out of this prison in the 20 years I’ve been here. If you’re innocent, he’ll walk you out the front gate.’”

Which is what happened earlier this year. After Lyman’s murder conviction was overturned in February, Ney and his wife Judy took him out for a ribeye and a double smoked bourbon and put him up in their guest room that first night.

In July, the case was dismissed altogether. Now, if all goes according to plan, Lyman will himself be starting law school next fall, “and if I can be half the lawyer Richard was, I’ll be really good. Maybe someday, I’ll come across someone like me, who really needs a lawyer who’s not afraid.”

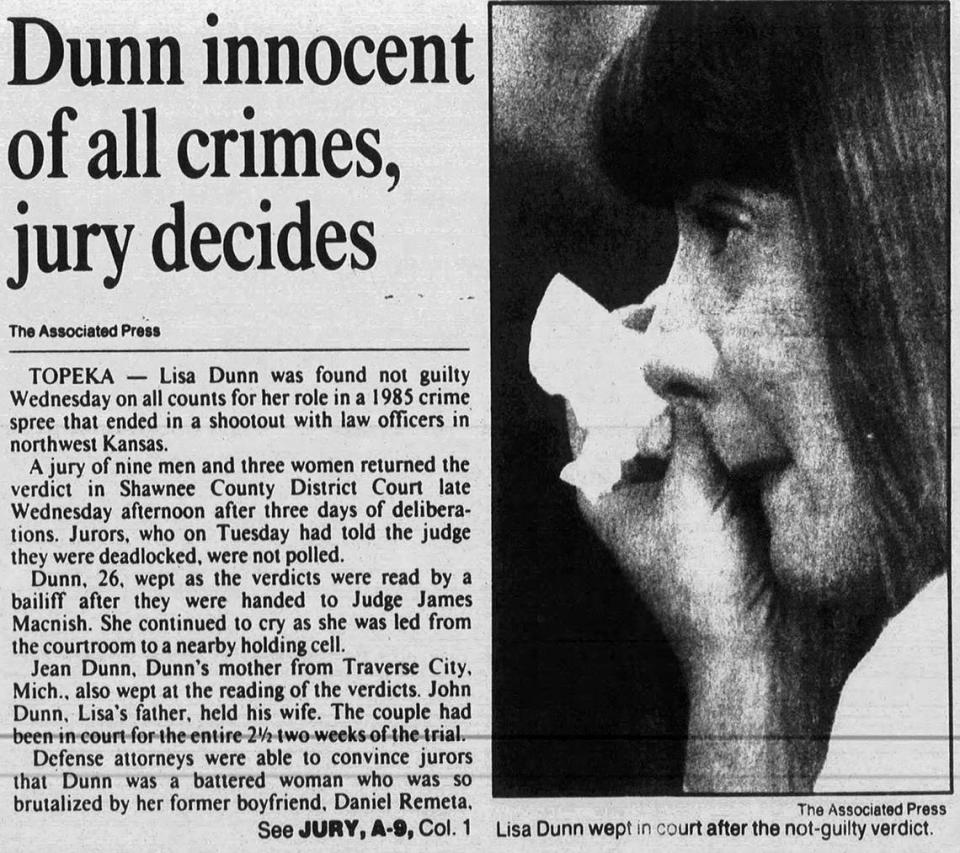

‘Battered woman syndrome’ defense won acquittal

The former Lisa Dunn, now Lisa Dant, whose bad boyfriend, Daniel Remeta, saw himself as some kind of “second coming of Charles Manson,” dragged her 18-year-old self along on a trip that turned into a multistate killing spree in 1985.

Originally, she was not only found guilty of murder, too, but was given so many consecutive life sentences that she would first have been eligible for parole at 103. But after Ney used the “battered woman syndrome” defense at her 1992 retrial in Topeka, she was acquitted of all charges.

Dant cried while telling me about how Ney flat-out saved her life. But then, “I start crying whenever I start thinking about Richard, an incredible human being who never stopped being part of our family. He was such a good attorney, he could have made a bazillion dollars anywhere, but he fought for the people who have no power, and the integrity of that. … He was a voice for someone like me, who felt no one would ever listen or believe or understand. But he could see that I really was an innocent person.”

Ney had actually left Kansas by the time of her retrial, and had taken a job as the chief federal public defender for Hawaii. Yet he used his two-week vacation to come back and defend her in court.

“He had to leave before the jury came back,” three days after closing arguments, “and had to hear about the verdict on the phone! My husband and I married 28 years ago, and I look at my two wonderful daughters and grandson and know I wouldn’t have this life” at all if not for Ney. Now a 57-year-old grandma in her hometown of Traverse City, Michigan, she believes that “everything turned out because he never gave up on fixing what had been done wrong to people.”

Had to tell Dennis Rader’s wife she was married to BTK killer

Ney was also the attorney who represented the BTK killer, Dennis Rader, at his first court appearance, and it fell to him to inform Rader’s wife that she was married to a serial killer. “She really did not know,” his widow Judy Ney told me.

He also sometimes spoke to Sarah Gonzales-McLinn, the young woman I’ve written about several times who was originally sentenced to a “Hard 50” after killing her abuser in Lawrence in 2014, when she was 19. Though as Gonzales-McLinn, who has a clemency petition pending, said in a message to me on Sunday, “He wasn’t even my attorney, technically.”

Ney was, however, “a steady voice over the phone who I called in my moments of doubt and fear. … Mr. Ney was someone I knew would give me a perspective I couldn’t see from the closed environment of incarceration. And he never charged me, not once. … He always spoke with wisdom and respect. If I could tell him anything right now, it would be thank you for showing me kindness and compassion when the world around me was cold and terrifying.”

Richard Ney was born in Galesburg, Illinois, where he was the editor of his high school newspaper. He lost his dad, who had diabetes, when he was only 12, so “it was pretty lean” money-wise, Judy Ney said.

He put himself through MU’s Missouri School of Journalism in three years, with a combination of student loans and a job working the quiet third shift at a hotel in Columbia where he could study at the check-in desk.

He really only went on to law school, at Boston University, hoping that it would make him a better journalist. But while there, he worked with the Roxbury Defenders Unit, and “that got him interested in criminal defense,” Judy Ney said.

He did go back to Illinois after BU, and worked at the Peoria Journal Star as an investigative reporter and an editor. But as soon as a job as a public defender came open in Danville, Illinois, he went for it.

It was there, where both he and Judy were active in community theater, that he met his future wife, a teacher. A big fan of musical theater, and later opera, Richard got to know Judy when both were in local productions of “The Pajama Game” and “Cabaret.”

Together, the Neys raised six children — two daughters from Judy’s first marriage, two sons they had together, and another son and daughter they adopted from Ethiopia.

Their son Gideon, who teaches at Johnson County Community College, Judy said, is named after the “petty thief” Clarence Gideon, whose handwritten petition to the Supreme Court about his conviction for breaking into a Florida pool hall led to Gideon v. Wainwright, the 1963 decision that says everyone is entitled to counsel, whether he can afford it or not.

Opened first public defender’s office in Sedgwick County

They moved to Kansas in 1984, when Ney was hired to open the first public defender’s office in Sedgwick County at only 28. He hired other young lawyers, and taught them, among other things, his wife said, “how people should be treated. If somebody called for an attorney and you were in, you took that call,” no matter who was on the line.

He ran the office for eight years before moving to Hawaii in 1991 to become the state’s federal public defender. But he returned five years later, and went into private practice in 1996. In an interview for a publication of the Kansas State Board of Indigents’ Defense Services earlier this year, he said he came back because he missed Wichita and because “I’m more of a street lawyer kind of guy.”

Like both of his parents, he suffered from diabetes, and had a quintuple bypass in 2010. Having spent so much time visiting his father in the hospital as a kid, he did not want to spend his final days in one. Last Wednesday at around 3 a.m. he died at home, where at his insistence, the Christmas tree had already been trimmed.

Judy Ney remembers one Christmas afternoon he spent with a client, because the guy could only see his children that day if an officer of the court were with him. “I always knew his clients came first.”

Nothing made him angrier, she said, than when someone said, “I don’t know how you can defend those people. And you couldn’t say ‘crimes.’ You had to say ‘alleged crimes.’”

Even the Bible, she said, talks about “the least of these,” but Richard Ney saw nobody as least, or as any less valued than anyone else.

He didn’t want a funeral, so there won’t be one. But all kinds of people were lifted by his life, and saddened by the end he’d told almost no one outside his family to expect. “Those of us who had the privilege to try cases against Richard,” the Sedgwick County District Attorney’s office posted on Facebook, “were better for the experience.”