Inside America's cold case revolution: new super effective DNA-matching technique prompts privacy concerns

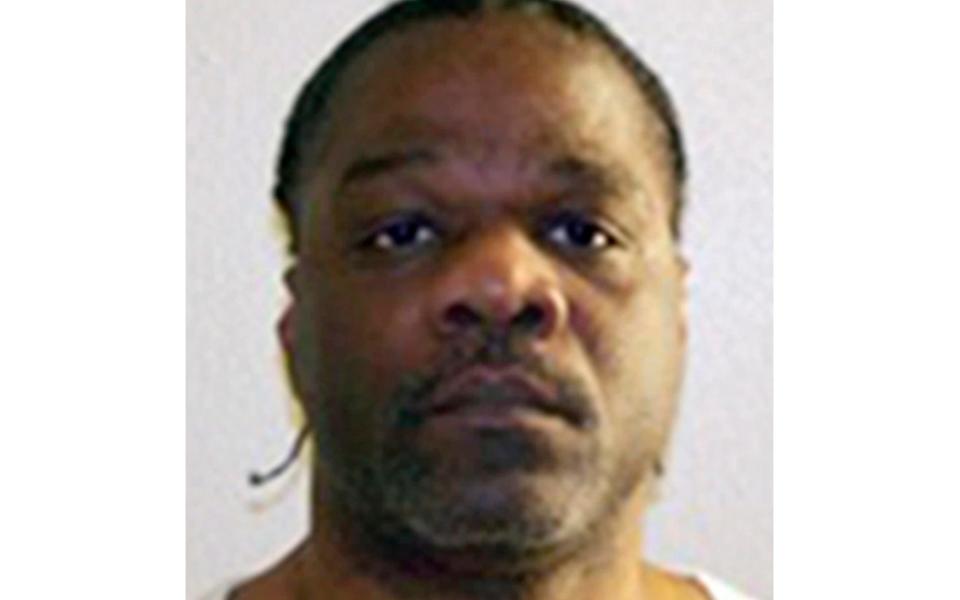

Convicted killer Ledell Lee protested his innocence up until his death in 2017 by lethal injection at an Arkansas county prison.

Lee was accused of strangling and fatally bludgeoning a 26-year-old woman in 1993, but his prints were never found on the murder weapon and testimony putting him at the scene was later discovered to have been flawed.

Four years after his death, the state agreed to allow a new test of the DNA evidence from the crime scene that used sophisticated genome sequencing.

What it showed was conclusive - they had executed the wrong man.

The DNA was not a match for Lee, but another - still unknown - killer.

“The investigation into the case remains open due to the possibility of a future database ‘hit’ to the unknown male DNA or unknown fingerprints from the crime scene,” Nina Morrison, Senior Litigation Counsel at the Innocence Project, said in a statement last week.

There was no match found in the FBI’s national database, but Lee’s family is hoping that a relatively new forensic technique - which identifies suspects through DNA similarities with relatives - will help finally clear his name.

Investigators in the US have had considerable success with it so far. Since identifying in 2018 the so-called Golden State killer, who murdered 13 people and raped dozens in the 1970s and 80s, they have solved more than 50 other cold cases.

While the development has been welcomed by the Innocence Project and those fighting for justice for the accused, others have serious concerns about the implications for privacy.

Some of the more rudimentary DNA testing is being done by generating a subset of key markers from a person’s DNA code, like an abridged version of a book.

But increasingly, investigators are turning to private companies for whole-genome sequencing, which reconstructs a person’s entire DNA code and gives investigators the tools to solve cases much quicker and easier.

They then compare the DNA code with data from ancestry sites such as GEDMatch and FamilyTreeDNA.

Unlike state and federal criminal databases, theirs are enormous, including millions of people who have voluntarily uploaded their own genetic information.

Many, such as Ancestry.com and 23andMe, opted not to make them accessible to law enforcement.

But data from GEDMatch, a popular website for tracking down lost family members, has helped police find a suspect in a case that reached trial just last week in Florida.

Former sailor Thomas Garner, 61, was arrested in March 2019 for the 1984 killing of 25-year-old Pamela Cahanes, his fellow classmate at the Orlando Naval Training Center, after genetic firm Parabon NanoLabs re-tested a semen stain found on Miss Cahanes’ underwear.

Further testing on the DNA sample allowed experts at Parabon to create the unknown suspect's “family tree,” which ultimately led the authorities to Garner.

He has now been linked to a second cold-case killing in Hawaii around the same time, in 1982.

GEDMatch changed its access policy not long after Garner’s arrest, requiring users to explicitly “opt in” to law enforcement searches.

Ethicists said the decision ensured that users would be properly informed about how their profiles would be used.

“People using genetic genealogy databases for their own purposes never anticipated this kind of access to their genetic information or that information being used to identify people they’re related to,” said Amy McGuire, director of the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the Baylor College of Medicine.

There is “a genuine tension between wanting to protect consumers and be respectful of their wishes and recognising that working with law enforcement provides a social benefit,” she said.

A recent Baylor College of Medicine survey last year found 91 per cent of respondents favoured law enforcement using consumer DNA databases to solve violent crimes, and 46 per cent for nonviolent crimes.

The UK Government has conducted studies looking at how such DNA sequencing would work in Britain, but a decision on the controversial technique is yet to be made.

In January of this year, GEDMatch adapted its policy to allow its entire database to be used for forensic searches related to unidentified remains.

This gave scientists from the DNA Doe Project their break in identifying the body of an unknown woman in Indiana, thought to have been the victim of a serial killer who was prolific in the 1980s.

They had a tiny biological sample, which contained only 0.3 nanograms, or 300 trillionths of a gram, of genetic material.

It was first matched with just a handful of distant cousins, but when GEDMatch policy was changed the scientists suddenly found much closer matches which enabled them to identify her as Jenifer Noreen Denton, a 24-year-old mother-of-one from Illinois.

They are now working on trying to find her killer.

In Lee’s case, the Arkansas State Crime Laboratory has not yet searched the state database, despite being pressed to do so by the Innocence Project and Lee’s family.

“We are glad there is new evidence in the national DNA database,” said Patricia Young, Lee’s sister. “We can only remain hopeful that there will be further information uncovered in the future.”