Inside the Conservative Movement's Long Con to Capture the Courts

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

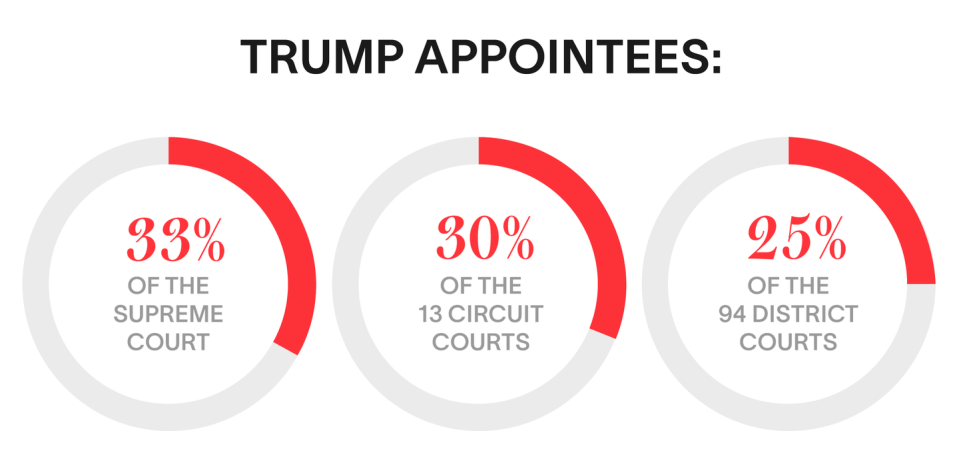

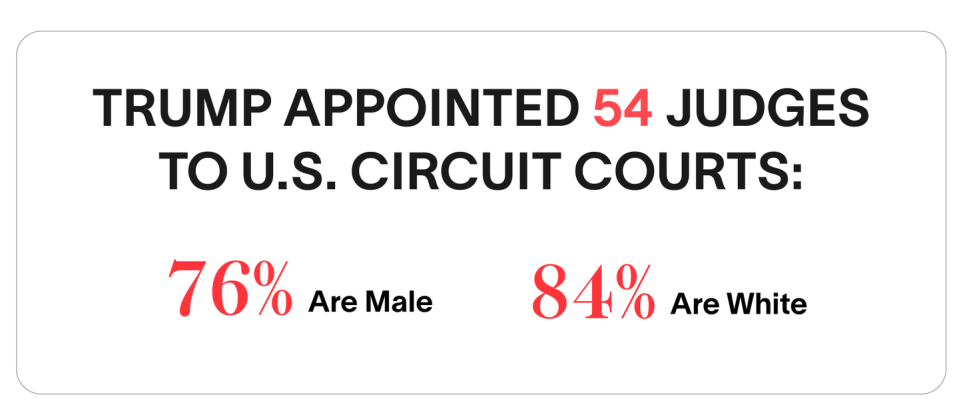

Trump’s 226 appointments to the trial, appellate, and Supreme courts will stand as one of his foremost legacies, and all but certainly his most enduring: some appointees, mostly young and with life tenure, will be on the bench late into the twenty-first century. Were Barrett to serve until her late eighties as Ginsburg did, she would be on the court until about 2060; Kavanaugh and Gorsuch could be there past 2050. Trump’s three justices in a single term are one more than Obama, George W. Bush, and Bill Clinton each named over two terms. He appointed fifty-four judges to the circuit courts—which are the final word on the overwhelming share of appeals, since the high court accepts few—just one less than Obama over eight years. When Trump left office, his picks comprised one-third of the Supreme Court, 30 percent of the thirteen circuit courts, and more than one-quarter of the judges at the nation’s ninety-four district courts. Like Trump’s administration and the Republican Party, his appointees are not a diverse group. Seventy-six percent are male (compared to 58 percent for Obama) and 84 percent white (64 percent for Obama).

In McConnell’s Senate, confirming Trump judges took precedence over everything else. The right-wing RedState.com wrote—approvingly, of course—of “the bloody-mindedness of Mitch McConnell and Chuck Grassley in ramming those nominees through the system.” Six months before the 2020 election, Grassley’s successor as Senate Judiciary Committee chairman, Lindsey Graham, urged federal judges in their sixties to retire so Republicans, rightly fearful of losing the Senate majority and the presidency, could fill the seats. McConnell, breaking yet another norm, had the Senate continue to confirm judges after Trump’s defeat, vowing he’d “leave no vacancy behind.” Since 1897, the Senate had confirmed just one judicial nomination of those pending after the presidents who made them lost election. It confirmed fourteen of Trump’s. Even as Republicans complained that Democrats would pack the courts once Biden took office to offset Trump’s judges, they actually were continuing to do so.

More than any president before him, Trump picked young lawyers for the lifetime jobs. Many lacked the experience expected of federal judges. Democrat Dick Durbin of Illinois, who in 2021 became chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, told me that more than once he’d said to Trump officials at confirmation hearings, “So, let me get this straight: You couldn’t find one conservative Republican attorney in the state . . . who has had any courtroom experience or experience as a state judge?” More often than in past administrations, the American Bar Association rated some nominees “not qualified,” which didn’t deter Republicans from confirming them. However, forty-four-year-old Jonathan Kobes, an aide to Republican senator Mike Rounds of South Dakota, needed Mike Pence to break a tie for his confirmation to the St. Louis–based Eighth Circuit in 2018. Kobes was the first federal judge in history confirmed by a vice president’s vote. Lawrence J. C. VanDyke, nearly forty-seven, was confirmed in late 2019 to the Ninth Circuit, although the ABA found him “not qualified” based on “strong evidence” from sixty lawyers and judges. Its harsh evaluation, which conservatives denounced, said those consulted about him called VanDyke “arrogant, lazy, an ideologue, and lacking in knowledge,” and said he “has an ‘entitlement’ temperament, does not have an open mind, and does not always have a commitment to being candid and truthful.”

Some nominees had troubling records regarding their attitudes toward racial minorities, women, and LGBTQ people. Tim Scott of South Carolina, the only Black Republican in the Senate, took to the Wall Street Journal to object, “We should stop bringing candidates with questionable track records on race before the full Senate for a vote.” Scott was able to block several, given Republicans’ slim Senate margin.

All of Trump’s choices had one thing in common: serious conservative bona fides. As McConnell had half joked to the Federalist Society, ending the filibuster opened the door to “crazy right-wingers” who never would have been confirmed in the past. Three times Trump nominated forty-year-old Matthew Kacsmaryk, who’d opposed legal protections for LGBTQ people and said they had mental disorders, before Republicans finally approved him for a Texas trial court in 2019. Confirmed to another Texas court that year was Michael J. Truncale, sixty-one, who’d called Obama an “un-American imposter”; the only Republican to oppose him was Obama’s 2012 rival, Mitt Romney.

Another example: Neomi Rao, Trump’s forty-five-year-old czar against federal regulations, who replaced Kavanaugh on the D.C. Circuit Court that handles most challenges to such rules. Rao seemed a singularly odd choice, given the allegations Kavanaugh had faced during his confirmation: At Yale, she’d written that women who were sexually assaulted bore blame if they’d been drinking. Facing bipartisan opposition initially, she wrote to Judiciary Committee leaders, “If I were to address these issues now, I would have more empathy and perspective.” That assuaged Republican Joni Ernst of Iowa, an assault survivor who’d called Rao’s writings “abhorrent.” Separately, Rao privately reassured Republican Josh Hawley of Missouri, who’d worried that she was soft on abortion. Once on the D.C. court, Rao reliably took the administration’s side in cases important to Trump. She opposed Congress’s subpoenas of his financial records, for example, and upheld the Justice Department’s dismissal of the conviction of his former national security adviser Michael Flynn—a ruling that the full appeals court overturned decisively.

Perhaps the quintessential Republican judge of the Trump-McConnell era, however, was Justin Walker, a baby-faced political networker to rival Kavanaugh in his time. In less than a year between 2019 and 2020, Walker went from being a thirty-eight-year-old associate law professor in Louisville, Kentucky, to a federal district judge there and then a member of the powerful D.C. appeals court. The ABA had advised that Walker, with no trial experience, was unqualified to preside over a district court. That didn’t matter to Republican senators: he was a protégé of the majority leader. On March 13, 2020, McConnell and Kavanaugh flew to Louisville to participate in Walker’s formal investiture as a federal judge, an event that was remarkable for the openly political banter.

There, McConnell recalled that they’d met when Walker was eighteen; as a favor to Walker’s grandfather, the senator talked to the teenager for a school paper on the 1994 “Republican Revolution.” The party’s takeover of Congress that year was “the most exciting thing that had ever happened in my life,” the boy said, in McConnell’s recounting. “Clearly he had excellent political taste from quite a young age,” McConnell quipped. Walker interned in McConnell’s office, worked on Bush’s 2004 campaign, and clerked first at the D.C. court for Kavanaugh—who was only too happy to hire a protégé of the Senate Republican leader—and then for Justice Anthony M. Kennedy on Kavanaugh’s recommendation. Kavanaugh, in his judicial robe, told the audience that he recalled just where Walker sat when Kavanaugh taught him at Harvard Law School.

Walker, also in a black robe, recognized each mentor. “It has been extremely important to me that Kentucky’s senior senator is Mitch McConnell,” he said, and then led the audience in applause. As for Kennedy, Walker told a weak joke that would become an issue in his next Senate confirmation hearing; in the telling, he said “the worst words” he’d ever heard was Kennedy’s disclosure that Chief Justice Roberts would uphold Obamacare. Of Kavanaugh, Walker joked, “What can I say that I haven’t already said”—he paused for effect—“on Fox News?” That nod to his ubiquitous support for Kavanaugh during the confirmation fight was a bit awkward. But what followed—an ideological call to arms—was simply inappropriate from a judge. Walker compared Kavanaugh to St. Paul: “Hard-pressed on every side but not crushed, perplexed but not in despair, persecuted but not abandoned, struck down but not destroyed. Because in Brett Kavanaugh’s America, we will not surrender while you wage war on our work or our cause or our hope or our dream.” He stopped for applause, then closed by thanking Trump and “the Senate majority,” adding snarkily, “And to the Senate minority—no hard feelings.”

On the district court, Walker soon sparked a controversy that resonated beyond Louisville. With coronavirus infections peaking, the Democratic mayor had issued a directive against drive-in Easter services. Walker blocked it and lashed out: “On Holy Thursday, an American mayor criminalized the communal celebration of Easter.” Twenty pages later he ended with musings on the meaning of Jesus’s resurrection to those eager to attend services: “The reason they will be there for each other and their Lord is the reason they believe He was and is there for us." Even a conservative analyst wrote that Walker’s rhetoric was “over the top,” and that he could have settled the matter with a fifteen-minute phone call among the parties. A liberal commentator, describing Walker’s order as more like “a screed against Democrats” on far-right Breitbart.com, said it exemplified what scornful judges called “auditioning” by Trump appointees—as in, primping for a higher court seat by showing off their conservatism. That’s what some associates had previously said of Gorsuch and Kavanaugh before their promotions. But Walker didn’t need to audition. Eight days earlier Trump had nominated him for the D.C. appeals court. Walker had followed the political path Kavanaugh helped pave for conservative judges years before. Already some on the right had tagged Walker as a future justice. That prospect would have to wait: In 2021, Democrats took over the White House and Senate.

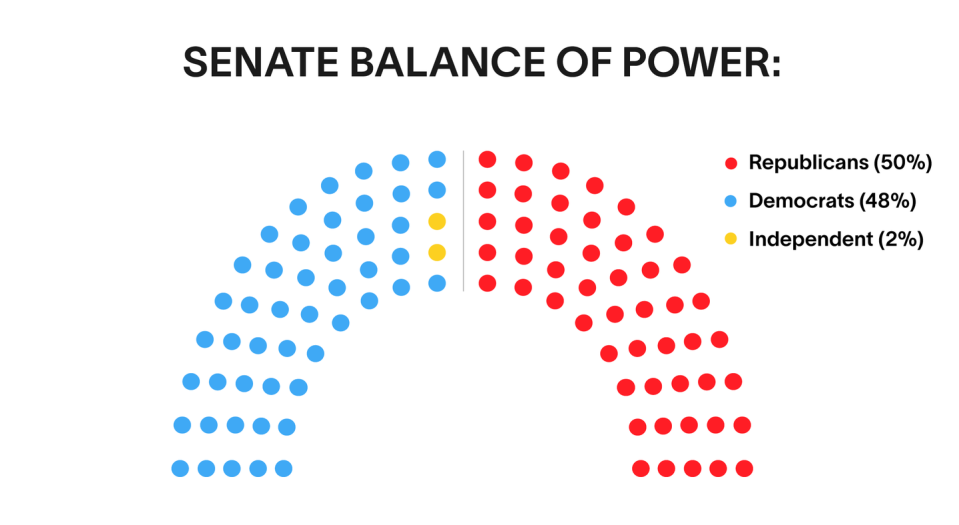

Initially, Democrats’ elation at Biden’s victory was offset by dismay at their apparent failure to capture a Senate majority. Few expected Democrats could win both runoff elections in Georgia, which would give them control of a 50–50 Senate with Kamala Harris’s tiebreaker vote. If McConnell remained in charge, they knew, many Biden judicial nominees would hit a wall. As courts scholar Russell Wheeler at the Brookings Institution had written, “We are reaching the point that confirmations stop unless the same party controls the White House and Senate.” Yet the Democratic candidates in Georgia—a Black man and a Jew—amazingly did win their elections January 5, 2021.

Given Democrats’ precarious margins in the Senate and House, most liberal activists dropped their unrealistic demand that Congress expand the Supreme Court so Biden could add progressive justices. Even so, after years of Republicans thwarting Obama’s nominees and then railroading Trump’s, Democrats were primed to act more aggressively than in the past to shape the judiciary. The pressure to do so was bottom-up, from the party’s base, donors, and progressive groups. In a break from past elections, more Democratic voters than Republicans had said that an important factor in their choice for president was concern about Supreme Court appointments. That reflected in part a backlash to the Kavanaugh and Barrett confirmations. Emboldened progressives forced eighty-seven-year-old Feinstein, disdained as too conciliatory toward Republicans, to relinquish her role as party leader on the Senate Judiciary Committee. Durbin became chairman once Democrats took the majority.

Copying a page from Trump and the right, progressive groups were ready with lists of potential judges for Biden. One group was the American Constitution Society, the left’s weak imitation of the Federalist Society, now led by former senator Russ Feingold. Activists had canvassed lawyers, law professors, and local officials nationwide during the Trump years to vet prospects for judgeships should a Democrat become president. They emphasized diversity of race and gender, for a judiciary that “looks like America,” as Biden put it, but also professional and educational variety: fewer corporate lawyers and prosecutors, more public defenders, labor and legal-aid lawyers, and civil rights advocates. Fewer Ivy Leaguers, more state school alumni. As usual, Democrats didn’t focus on judicial philosophy and ideology like Republicans did, though certainly their criteria would yield generally progressive candidates. Activists also urged Senate Democrats to follow Republicans’ lead and end the blue slip tradition that gave opposition senators a veto over nominees from their states. Chris Kang, the former Obama adviser, said Senate Republicans mostly from southern states had blocked nearly twenty Obama nominees, all of them women or minorities, by withholding their blue slips.

No question, Democrats would be more partisan going forward. The question was whether they could beat Republicans at the game. Brian Fallon, the former Senate and Hillary Clinton adviser who was Kang’s cofounder of the liberal group Demand Justice, was skeptical even as he pressured Democratic leaders. “Mitch McConnell will obliterate norms without batting an eye,” he said. “Democrats constitutionally—no pun intended—don’t have that gene. They like the system to work. They like the government to function by norms.”

That certainly included Biden, long suspect on the left for his record as a moderate institutionalist on the Judiciary Committee, back to the Thomas hearings thirty years before. But the new president was receptive to the partisans’ push for a harder line, despite his promise to work with Republicans. He endorsed the call for diverse judicial candidates outside the corporate and prosecutorial mold. He promised a commission to examine potential changes to the judiciary, including term limits and additional judgeships. To expedite nominations, Biden agreed not to wait for ABA evaluations. “People are approaching this with a different sense of urgency,” said Paige Herwig, a White House counsel. “And they understand: They saw what the Trump administration did for four years.”

Biden didn’t inherit nearly as many vacancies as Trump had, though McConnell didn’t quite fulfill his vow to leave none behind. Circuit courts had five openings and federal trial courts more than sixty. When Garland finally won Senate confirmation—as Biden’s attorney general—his seat on the D.C. appeals court opened. Other vacancies loomed: Some judges had put off retirement rather than let Trump fill their seats, and about sixty were eligible by their age and years of service to take “senior status,” a limited role that allows presidents to name a full-time replacement. Those included more than a third of appellate judges.

Rebalancing the Supreme Court, however, was a lost cause. Breyer, eighty-two when Biden took office, was widely expected to retire before long, now that a Democrat would nominate a successor. Biden had promised to make history by naming the first Black woman to the high court. Ideologically, however, that would be an even swap, leaving the court’s balance unchanged. From the Supreme Court through lower courts, Republican appointees stood as potential roadblocks to the agenda of Biden and congressional Democrats—what liberal writer and lawyer Dahlia Lithwick called the “dead hand of the Trump administration that strikes down every single thing that Biden does in the coming years.”

That specter was evident in the new president’s first week: a Trump trial judge in Texas, in a case brought by the state’s Republican attorney general, blocked Biden’s one-hundred-day moratorium on deportations— his first step in reviewing Trump’s inhumane, xenophobic immigration policies. Days later, a three-judge panel of the D.C. Circuit Court—all Trump appointees—gave a green light to a Trump directive to turn away children seeking asylum as health risks, a policy Biden opposed. The Biden administration would face a quandary in deciding whether to appeal such cases all the way to the Supreme Court. More than a year before the election, Wheeler, the judiciary expert, wrote of the potential that the conservative court would stymie laws and regulations from a Democratic president and Congress. That, he wrote, in turn could trigger progressives’ attacks on the court’s legitimacy, much like in the New Deal era, reviving and intensifying the pressure for court-packing.

It had been judicial appointments more than anything, even more than cutting taxes and regulations, that kept the Republican establishment in thrall to Trump. That was the Faustian bargain party leaders made for five years with the self-dealing charlatan who provoked an existential crisis for their party, and for democracy. Chief among them: McConnell, the man who denied Garland his rightful seat on the high court for Trump to fill with Gorsuch, rammed Kavanaugh through and then engineered Barrett's confirmation just days before elections that would end Trump's presidency and ultimately Senate Republicans' majority.

Reelected in 2020 to a seventh six-year term, at seventy-eight, McConnell will be around for his party’s next chapter. Republicans could well retake control of the Senate and House in 2022, given the close margins and the midterm jinx for the president’s party. Whether he's leader of a minority or majority, McConnell will do what he can to obstruct Biden’s agenda and especially his judicial nominees. But however the elections for Congress and the White House play out, McConnell can be satisfied that he, more than any single person, ensured that the Supreme Court will almost certainly remain in the conservatives’ corner well beyond his lifetime.

Adapted from Dissent: The Radicalization of the Republican Party and Its Capture of the Court ©2021 Jackie Calmes and reprinted by permission from Twelve Books / Hachette Book Group.

You Might Also Like