Inside the Dark Underbelly of New York’s Most Glam Strip Club

The customers at the club knew her as Heidi. But her real name was Margaret O’Sullivan, she was 19 years old, and she was petrified.

It was December 2021 and O’Sullivan was alone in a room with a man at Sapphire Gentlemen’s Club, a joint that bills itself as New York City’s “finest strip club.” The man, who she’d been instructed was a “loyal customer,” was impatiently waiting for her to give him oral sex, her lawyers later wrote in a legal complaint.

But when she told the customer, who was sitting there “fully exposed,” that she just wanted to dance for him, he yanked his pants up and stormed out.

“I remember being scared,” O’Sullivan told The Daily Beast. “I was like, ‘Gino’s going to get mad at me.’”

She was right, the suit alleges. But first, Gino, one of the male employees at Sapphire known as a club “host,” apologized to the customer. Only then did he round on her, “visibly irate,” as the complaint puts it, and start yelling.

“I was in pieces,” O’Sullivan recalled, adding that the encounter left her in tears. She lasted less than a year at Sapphire before she quit in the throes of what she described to The Daily Beast as a “full mental breakdown” that, according to her lawsuit, ultimately left her hospitalized.

In June 2022, she was one of two former dancers named as plaintiffs in a $25 million class action suit filed against the club and its owners by the labor attorneys Jon Norinsberg and Bennitta Joseph.

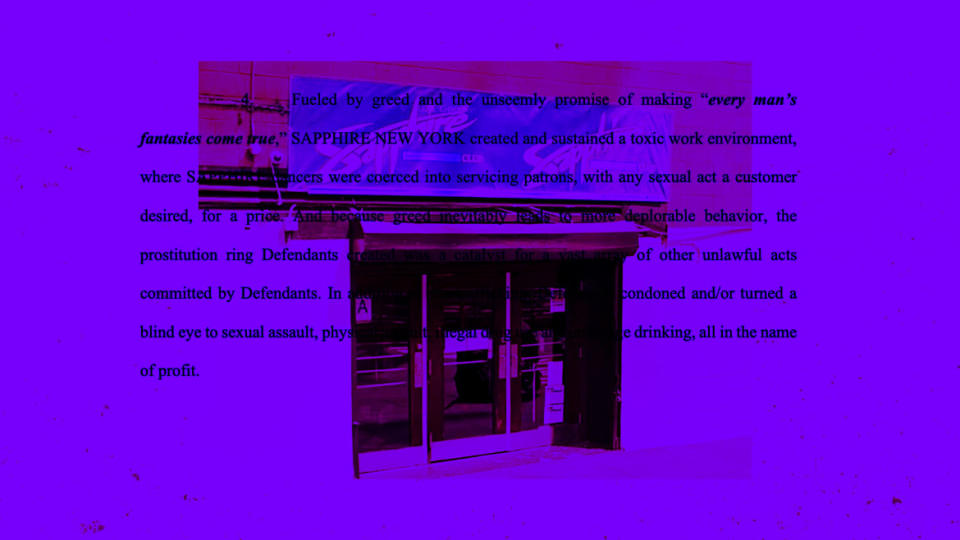

Their complaint claims that, fueled “by greed and the unseemly promise of making ‘every man’s fantasies come true,’” Sapphire Gentlemen’s Club created a toxic work environment in which dancers were coerced into performing “any sexual act a customer desired, for a price.”

Meanwhile, it alleges, club management turned a blind eye as its hosts “behaved like Gods”—manipulating dancers with impunity, allegedly pushing them to take drugs, drink to excess, and prostitute themselves. If a performer resisted, she risked “retaliation, through threats, intimidation and physical assault”—if she wasn’t fired or frozen out first. Some, like O’Sullivan, crumbled under the pressure, with her mental health deteriorating to the point of collapse.

“It was the most evil place I could imagine being in,” O’Sullivan said.

Margaret O’Sullivan

An attorney representing Sapphire, Jeff Kimmel, called the suit “a litany of false allegations solely designed to garner publicity” in a statement to The Daily Beast. He asserted that the club has “strictly enforced” policies in place against drugs and prostitution, and that any allegations that ownership or management knew about, much less condoned, any illegal activity “is completely fabricated.”

“Sapphire will vigorously defend against these false, frivolous and defamatory allegations,” Kimmel added.

Joseph and Norinsberg have disputed Kimmel’s response, saying their investigation had revealed the club’s “grave indifference to the safety and well-being” of its dancers. “We are confident the truth will come to light through litigation, and that Sapphire will be held fully accountable for their unlawful and abhorrent conduct,” they added.

Since the lawsuit’s filing, Kimmel and his team have filed multiple motions attempting to compel the case into arbitration, a path that would keep the suit out of court and the public eye. Joseph and Norinsberg have repeatedly opposed this, arguing that a federal law enacted last year protects their suit from forced arbitration. It is unclear when a definitive ruling on the issue will be handed down.

In that time, at least a dozen other former dancers have reached out to Joseph and Norinsberg, they said. Given Sapphire claims on its website that it employs “8,000 lovely ladies,” the firm believes that there could be more than 1,000 other people out there who could qualify as victims of the club’s alleged misconduct.

“There are many measures in place to ensure the safety of everyone at the Club, including a clear and conspicuous complaint and/or reporting procedure allowing for anonymous complaints,” Kimmel’s statement read. “The safety, well-being and happiness of dancers is of foremost importance to the club.”

The Crown Jewel

“Without these women, there is no club,” said Elena, a woman who spent eight years working security at Sapphire. Not a party to the ongoing legal case, she spoke to The Daily Beast on the condition of anonymity since she still works in the industry. (“Elena” is a pseudonym.) “There’s no lights, there is no liquor, there is no party.”

Between its three locations, the club purports to swallow up more than 10,000 square feet of city real estate. Its East 60th Street location, which occupies the spot once held by Scores, the legendary club of Hustlers infamy, was the first of the three Sapphire sites to open in 2009. The younger sister to Sapphire’s original Las Vegas location, the New York joint was marketed upon opening as a “high-end… R-rated night club” by franchise managing partner Peter Feinstein.

Feinstein, who is named as a defendant in the suit, once described Sapphire as a place for a man “to escape and get away for a few hours, and then go back home and be a dad and a good husband.” Through Kimmel, who noted that his client is not involved in the management of Sapphire’s clubs, Feinstein declined to comment on the case.

With velveted walls, bottle service, pounding music, and the chance to ogle celebrity clientele—which, prior to the pandemic, reportedly included the likes of Busta Rhymes, Travis Scott, Ice-T, and Rob Kardashian—Sapphire New York proved exceedingly popular with tourists and locals alike, some of whom were willing to spend a small fortune in a single night.

“Sapphire is the most upscale of all the clubs in the city,” Elena explained. “Every girl wants to work there. When you go in there, it’s beautiful. It looks amazing. It looks like they really do take care of the girls.”

Sapphire on 60th Street in Manhattan.

Since its founding in 2002, Sapphire’s Las Vegas branch has been sued several times by its dancers, most of whom alleged the club had violated labor law by misidentifying them as “independent contractors.” In 2014, reversing a lower court’s opinion, the Nevada Supreme Court agreed that there’d been a misclassification. The club’s performers were employees, a justice wrote, but in being treated like contractors, they were, “for all practical purposes, ‘not on a pedestal, but in a cage.’” According to a suit filed by a dancer the next year, Sapphire ignored the high court’s decision. That claim was settled out of court in 2021.

In a more recent Nevada case, three women alleged they had been sex trafficked through Sapphire, as well as several other clubs and businesses. Their abuse, they claimed, had not only been facilitated by the clubs’ managers, but by state and local governments. Though a judge dismissed the part of the suit targeting the government in July, he refused to throw out the claims made against the clubs.

The judge wrote that one of the women, a Jane Doe, had “plausibly” alleged the club was “facilitating sexual abuse,” acknowledging her assertion that management could “‘see and hear all that occurred’” within its walls. (A lawyer for Doe told The Daily Beast that her claims had been put “on hold” pending an appeal to get the government defendants back into the suit. He added, “Then we’ll be going after Sapphire with all of our resources.”)

‘You Just Kind of Kept Your Mouth Shut’

Stephanie Krauel, the other plaintiff in the New York class action suit, started working at Sapphire regularly in 2015, adopting the stage name “Toni.” By that point, she had been flying up from Florida to dance in New York for the better part of a decade.

“The first year was great,” she told The Daily Beast. “Second year, things started to shift. And then, just gradually, it just kept getting worse and worse.”

One night, Krauel alleges in the suit, the host named Gino sent her into a room where a fully naked man was waiting for her. Krauel, shocked, assumed he was drunk. She asked him why his clothes were missing. “Then Gino comes in and says, ‘The waitress is going to be right with you guys,’” Krauel told The Daily Beast in an interview. “And [he] just walks out of the room.”

She bolted after him, more annoyed that he had wasted her time than anything else. Gino ended up sending another dancer into the room with the nude customer, she alleges in the complaint.

After that, the lawsuit claims, it became much harder to do her job. “Many, many, many times I would have a customer and he’d want to go in the back room,” Krauel explained. “Gino would talk to the customer”—hosts had to approve it if a dancer and a client wanted to use a private room—“and he would come back to me and say the guy was no longer interested. And then I would see the customer walking out of a room about an hour later with one of Gino’s girls.”

“If you wanted to continue working there, you just kind of kept your mouth shut,” Krauel said.

Though he is referred to only by his first name in the lawsuit, Gino’s identity is known to The Daily Beast. Reached by text this month, he provided an extended statement calling the lawsuit’s allegations “false, untrue, and completely without merit.” The statement claimed Gino had not been named as a defendant in the case, but noted that he would be “vigorously defended in court” nonetheless.

The author of the statement identified themselves only as “counsel for our client” but declined to provide their name and eventually stopped responding.

Once, Krauel said, she asked Gino what he was doing. “And he made a joke, saying, ‘Listen, we have good girls, and we have the other girls,’” she claimed.

Margaret O’Sullivan was one of the good girls.

A first-year student at the Fashion Institute of Technology, she had come to New York City on a scholarship that covered her tuition. To cover her other expenses, she thought about starting an account on OnlyFans, but worried about leaving a digital footprint that could come back to haunt her.

O’Sullivan’s roommate suggested she look into getting a job at Sapphire. Despite being, in her own estimation, a terrible dancer, she auditioned and was hired. “At first I thought it was really cool,” she said. “I was like, ‘Wow, I got hired at one of the biggest clubs in the city.’”

She was in awe of the celebrities she recognized at the club on the weekends, and intimidated by her fellow dancers, who seemed fearless and untouchable and aloof. Embarrassed by her own lackluster skills, she watched them closely, trying to imitate how they moved and talked to customers. When she got overwhelmed or self-conscious, she’d talk to Gino about it.

“He was how I felt safe there,” she said. “He’s where I went when I had any problem.”

Almost as soon as she started at Sapphire, O’Sullivan says Gino took her under his wing. He texted her throughout the week, encouraging her to put in as many hours as she could. He was good-looking and friendly—flirty, even—and O’Sullivan found herself developing a small crush.

But the texts became more frequent, with Gino encouraging her to pick up as many shifts as possible. He started taking her to “promo” events at other venues, the lawsuit alleges, where she would be pressured to drink to the point of blacking out and losing consciousness. “Over time, Gino grew confident that Ms. O’Sullivan was sufficiently compliant and began introducing her to his clients,” the suit states.

Hours after the December 2021 incident with the “loyal customer,” O’Sullivan recounted what had happened to two friends in text messages viewed by the Beast. “[M]y manager was like mad af at me being like this keeps happening to you,” she wrote to one, “...so I texted him saying I’m sorry they assume we’re gonna give them head because yal charge so much for a room for dances and when we don’t they freak out and leave and he then came up to me and yelled at me to never text him anything like that again and at the end of the night I had to apologize to him.”

To the other, she texted, “I’m so sad my manager like freaked at me. I think I’m coming back. Everyone here hates me I’m so uncomfy. I need money though.”

She felt trapped. “If I just stopped listening to him, stopped working with him and just did dances on the floor, I would have made—I don’t even know—a quarter or less of the money that I needed. I wouldn’t have been able to survive,” O’Sullivan said.

So she played nice. The next time he offered her a room, and a customer who expected something more than a dance, O’Sullivan didn’t walk out or complain. “Everything worked out. I gave him the money after, so he was like, ‘OK, she’s good. She’s not going to go against me anymore,’” she said. So she was given more rooms.

Elena, the female security guard, said she believed the claims. “Gino is…. a scumbag,” she said. “He’s a creep. Of the hosts, Gino was the bottom of the barrel of them.”

Elena was hired, she said, by Sapphire around 2014 to “clean house” around its New York locations. Her primary duty, as she understood it, was to gather information and give it to her bosses, who “would make the call on what to do… But nothing really ever got done.”

Gradually, her role began to feel “like eye candy,” she explained—window dressing, a distraction from the fact that the alleged illegal and abusive activity was still going on. Meanwhile, the lawsuit alleges, the hosts continued to use intimidation and the threat of retaliation to push dancers into prostitution: “As one former dancer put it: ‘Hosts behaved like Gods.’”

Breaking Free

By January, O’Sullivan was unraveling. At night, the 19-year-old would “snap into” being Heidi, the fake name she used at the club, dissociating from reality. She didn’t want to give up her life in New York City, but she didn’t feel like herself anymore. She was smoking marijuana everyday to cope, relying on it so heavily that it was giving her stomach problems. “I [felt] insane. I felt horrible,” O’Sullivan said. “I was suicidal all the time. I was having just the craziest thoughts all the time.”

O’Sullivan didn’t want to give up and go home, back to “being nothing,” as she put it, but by March she realized she couldn’t do it anymore. “It’s either, I’m going to die, or I have to go away somewhere,” she said.

Once the decision was made, leaving was easy. She texted her managers, ignored their replies, and “voluntarily checked herself into an in-patient mental health facility,” as the lawsuit puts it. “I was in and out of different treatment centers, like three or four times” in the ensuing months, she said. Around May, she started outpatient therapy. There were “ups and downs” that summer, O’Sullivan added, but “overall, I’ve been doing pretty good.”

She moved back home to her mother’s in Westchester, and applied to a nearby college’s nursing program. “It’s going to be a lot of work, but I think it’ll be better,” she said last fall, a few weeks before beginning classes.

Stephanie Krauel also found that it was surprisingly simple to just walk away when she decided to quit in April 2019. She had become increasingly frustrated and upset about the cycle of flying to New York and returning home to Florida “with less and less money” each time. “I felt low. It was a rough time,” she admitted.

Finally, she sat down and had a conversation with her mom, who simply advised her: “‘Don’t go back.’” So Krauel didn’t, deciding to forget about the dresses she’d left hanging in her locker back at the club.

Slowly, Krauel got back into bartending, and started working at a real estate franchise’s St. Petersburg office. But it still took her “a good year” to feel like herself again. “To be happy again, I guess,” she said. “I was just very depressed from the whole thing.”

Elena stopped working at Sapphire when the pandemic forced it to temporarily shutter. Then, “they just didn’t call me back,” she said. “They never fired me. They never told me not to come back. They just never called me to come back.” Her calls and texts received no response.

Eventually, Elena found another job in nightlife. The industry is “a small world,” she said, which made it difficult to say yes when a few of the women who later became involved in O’Sullivan and Krauel’s lawsuit reached out to her, asking if she’d back up their allegations as a witness. She figured it would be relatively simple for Sapphire and the other defendants named in the suit to identify her.

But she thought about it, and agreed to help. “I’m doing it for the girls. I know the truth,” she explained. “And I know what they’re saying is the truth.”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.