Inside the Fight to Fly Over National Parks

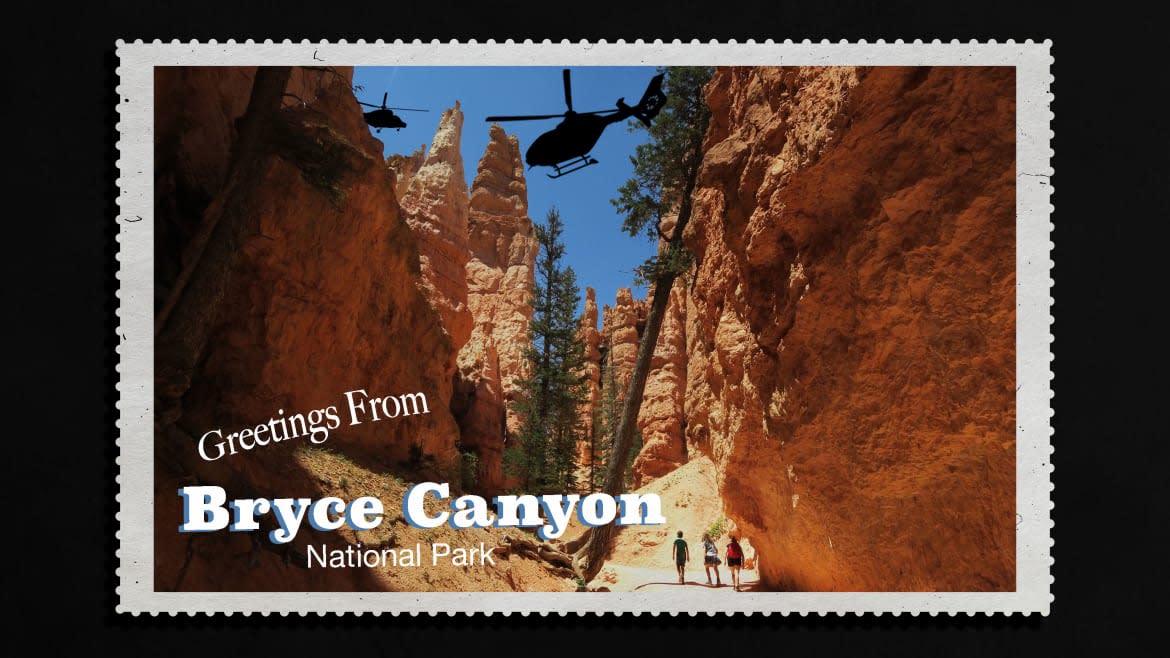

Bryce Canyon National Park in southwestern Utah is renowned for its hoodoos, thin spire-like rock formations that etch their way out of the amphitheaters and into the sky. During sunrise and sunset, the colors can range from dark violet to bubblegum pink and thousands of tourists come to witness them each year, some by car, some by foot, and some even by helicopter.

Helicopter tours are a popular way to see plenty of national parks. However, these air tours had pretty large latitude until recently, with no restrictions on how many flights could occur per year, on what times flights could occur, or even how low aircraft could go.

This might seem like it should be a priority for the National Park Service (NPS) and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), but their plans to manage these airspaces are more than 20 years overdue. Even though they released a long-awaited plan for Bryce Canyon in October, environmentalists argue that it’s poorly considered.

Following several helicopter crashes in the Grand Canyon (one of the worst happened in 1989, when a tourist plane crashed just outside Grand Canyon National Park, killing 10 tourists and injuring 11 more), Congress signed into law an Air Tour Management Act in 2000. This act required the NPS and the FAA to prepare an air tour management plan, demarcating how many flights could occur, where the flights could take place, and cruising ranges for any national park with more than 50 flights per year, none of which had previously been established.

The Grand Canyon would be dealt with separately, and promptly. However, the act included 23 other national parks for which the NPS and FAA were to jointly create management plans. Over 20 years later, the NPS and the FAA are just getting around to doing so.

The action finally came as a result of a court order. The Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), an environmentalist group of former and current public employees, sued the FAA in 2017 for effectively ignoring the Air Tour Management Plan of 2000 for almost 20 years. PEER won the suit, and the court set a deadline for Aug. 24, 2022, for the FAA and the NPS to release management plans for the 23 parks.

As a result of this pressure, the NPS and FAA recently released a draft air tour management plan for Bryce Canyon National Park, among others, that limits the amount of flights per year, as well as where the helicopters can fly, and at what time they can be airborne.

For Bryce Canyon National Park, the plan stipulates that helicopters can't fly during sunrise or sunset, within half a mile of the ground, and limits the number of flights to 515 per year.

While these restrictions seem to be a win for environmentalists, many instead argue that it’s a matter of perspective, especially since the plan doesn’t assess what these parks might be like without air tours.

Mike Murray, chair of the Coalition to Protect National Parks, an environmental organization composed of retired employees of the NPS, said that their group has been concerned about the planning process throughout and was ultimately disappointed by the agencies’ approach.

Instead of assessing the air tours with an option that doesn’t allow them at all, Murray says, the NPS and FAA instead set a minimum for pre-COVID flight numbers, maintaining the rate of flights in National Parks from 2017 to 2018. This was accomplished by claiming a “categorical exclusion,” a decision that essentially determined that these flights do not have a significant environmental impact, and therefore, isn’t worth assessing.

However, Murray called this “a capricious use of the categorical exclusion.” He argued that these air tour management plans are circumstantial, and suggests not enough science went into them. “How can you know it isn’t worth assessing if you’ve never assessed it?” Murray asked.

Ultimately, Murray views this as a bandage solution, instead of the actual regulation expected after 20 years. “Their plans are essentially making some modifications to the air tours, but not making a determination on whether they should continue,” Murray argued.

In a statement sent via email to The Daily Beast, the NPS summarized this decision, writing, “Each air tour management plan released includes measures that mitigate the impacts of commercial air tours on park resources, including designated routes, minimum altitudes, time-of-day restrictions, and other measures that are not included in the interim operating authority that authorized air tours prior to the completion of the plans.” They added that “[the FAA and the NPS] have evaluated the potential impacts of air tours on park resources and visitor enjoyment of those resources with respect to each air tour management plan and found that they did not result in significant impacts on park resources.”

Kristin Brengel, the senior vice president of government affairs for the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA), an environmental non-profit that works to preserve national parks across the U.S., said she was shocked by the decision and proposal, especially when it came to Bryce Canyon.

“Bryce Canyon is an obvious choice to restrict flights and for the NPS to send a message,” Brengel said. She added that in the draft proposal, air tours would still be permitted at popular overlooks and over popular trails.

“It’s a shame really—if you happen to be hiking and a helicopter tour flies over you, your whole day could be easily ruined,” she said.

But what really stuck out to Brengel was the process itself. All draft proposals require a public comment period by law. And while the law doesn’t say when this public comment period is supposed to take place, in most cases, it happens after the draft proposal is released, so that the public can voice concerns and plans can be adjusted accordingly.

However, this was not the case for these draft proposals, where the NPS held public comment before releasing them, a move environmentalists argue was done intentionally to limit public input.

“It was just wrong,” Brengel said, adding that “it didn’t allow the public to actually voice any concerns about the proposed plans.”

In response, the FAA wrote via email to The Daily Beast, “An important part of the process for each park was a public comment period and public meetings where the agencies presented the draft plan and answered questions. The FAA has sole authority to control U.S. airspace and thoroughly reviews the plans to ensure they comply with all safety protocols.”

Brengel went as far as to say that “the FAA clearly doesn’t like regulating airspace,” calling them the main obstructionist of the law.

Murray agreed, adding that he believes “the whole thing has been disingenuous from the start,” but still remains hopeful the NPS and FAA will adjust their methods for the remaining parks that require air tour management plans.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.