Inside ‘the hot zone.’ How a western NC field hospital launched in a week.

Laura Easton knew her staff was weary.

It’s nearly a year into the COVID-19 pandemic and hospitalizations at Caldwell UNC Health Care never had been higher. The Lenoir hospital’s chief executive saw fatigue in the sliver of their eyes, everything else hidden behind protective equipment.

They’d already modified plans to accommodate more patients, who just kept coming. Her counterparts across the region were facing the same.

With their facilities at capacity and infections on the rise, leaders of five western North Carolina community hospitals had come together to ask for help. They sought out Boone-based evangelical humanitarian organization Samaritan’s Purse to open a 30-bed field hospital in Lenoir.

“When the tents arrived, even in packaging in the parking lot, I could see a spark returning to the eyes of my staff,” Easton said.

On Thursday the small compound of white tents in Caldwell’s parking lot, just steps away from the helipad and the emergency room, treated its first patients.

It opened the same day North Carolina health officials announced for the first time since the pandemic began that 10,000 new cases had been identified in a single day.

Inside ‘the hot zone’

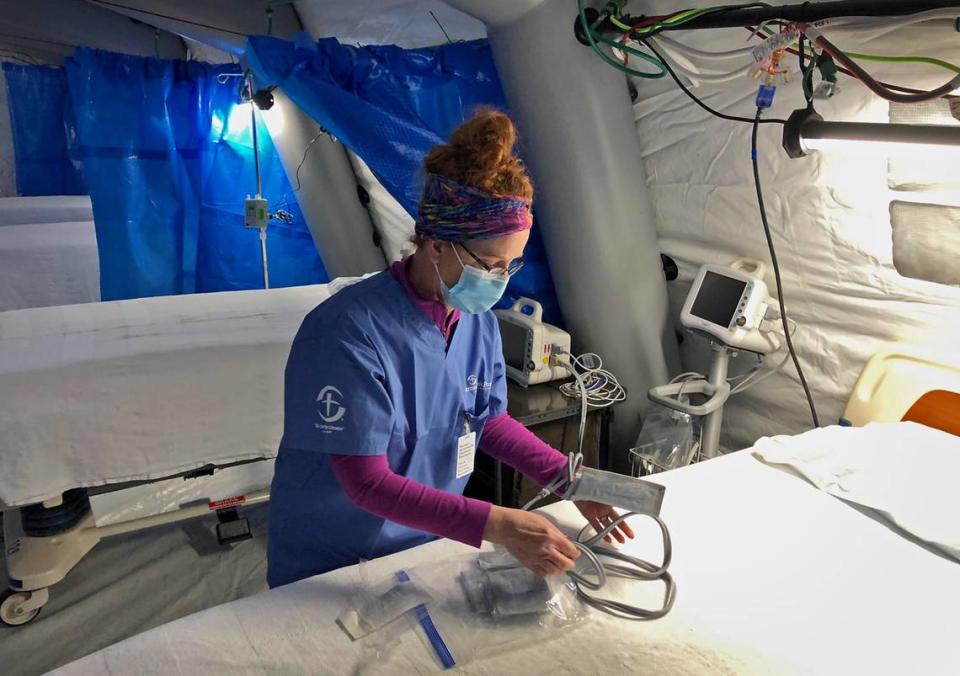

The field hospital has four tents with six to eight beds apiece, pharmacy and designated areas for staff to don protective equipment. Only then can they cross the pink tape on the floor marking the “hot zone.” This is where sick patients — but not those needing a ventilator to breathe — will stay, typically for a few days.

Patients transferred to the field hospital are COVID-19 positive and may need oxygen and other medications. When staff disrobe for the day, they undergo a rigorous decontamination process developed out of the organization’s Ebola response.

Shortly after 1 p.m. Thursday, a Caldwell County ambulance backed up to the fenced entrance and medical workers unloaded an older male patient on a stretcher.

He became the first hospital-admitted patient in North Carolina with coronavirus to be treated outside the walls of an established hospital.

By Friday, 13 patients were in the field hospital and officials had plans to transfer more.

Lenoir became the fourth city in the world to house a Samaritan’s Purse field hospital since the beginning of the pandemic, but the organization has a long history of medical responses for natural disasters, conflict zones or other humanitarian crises around the world.

Samaritan’s Purse treated more than 300 patients at its field hospital in New York’s Central Park this spring, according to local news reports. The organization also operated COVID-19 hospitals in Italy and the Bahamas. Now, it would turn its focus toward home.

Lenoir is currently the only active COVID-19 field hospital in the country operated by Samaritan’s Purse, though preparations for one in Los Angeles County are underway.

Kaitlyn Lahm, a spokeswoman for Samaritan’s Purse, said working all day in Lenoir can start to feel like any other disaster response, though they are usually at least one plane ride away and not less than an hour’s drive from her home base in Boone. But driving home on familiar roads is a sobering reminder.

“Wow, this is really close to home,” she said. “Now the disaster and the need is right in our backyard.”

‘It’s just bad’: Charlotte hospitals are filling up with COVID patients — and surge isn’t over

Once Samaritan’s Purse agreed to launch the hospital, officials worked to get waivers from state health officials for extra beds and OK out-of-state doctors and nurses to practice. They set up heat, oxygen and water lines to the tents and procured patient beds from a recently remodeled hospital in Eastern North Carolina.

“We built a hospital in seven days,” Easton said.

They’ve prepared for the winter weather, which descended on the region Friday.

“These tents have lived through tropical storms,” said Erin Holzhauer, medical director for the Lenoir field hospital. “The snow (will be) a new challenge for us but we’re prepared. The tents are heated for the patients so it will be nice and warm inside even though it’s real cold outside.”

The other four hospitals that will transfer patients to the Lenoir site, located in Hickory, Boone and Morganton, stretch across four western North Carolina counties that have seen a spike in cases along with much of the state.

COVID-19 cases began spiking after Thanksgiving, Easton said, many traced back to family gatherings and other holiday celebrations.

Her hospital typically has 55 to 60 patients per day. On Thursday, it had 107.

It’s an experience shared by her counterparts across the region, Easton said. In the last week, the five hospitals saw a 20% increase in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. At Caldwell, officials have converted the intensive care unit to care for COVID-19 exclusively. The operation recovery room became an ICU for non-COVID patients.

Precious few beds are left for people needing care for heart attacks, strokes or other serious conditions.

Her staff is committed but weary, Easton said.

She recalled two recent conversations: one with an employee who had returned to working in a hospital after years away, who told Easton, “I have cried more in the last two days than I have my entire life.”

The other was with an intensive care nurse who Easton stopped to talk with in a hallway.

“I’m really tired,” he told her. Then she asked about the bag he was carrying she recalled, a slight hitch in her voice.

He told her he was on his way to return belongings to his patient’s family and deliver the news their loved one wouldn’t survive.

The arrival of the field hospital has been a boon, she said.

“I think there was a underlying fear of, ‘Oh my gosh, where do we go next?’ Because we feel like we’re at our capacity,” she said. “When they saw those tents come and they heard that there were 30 nurses coming, (it felt like) the troops are arriving.”

New strain of COVID-19 isn’t in NC yet, but we should act like it is, Gov. Cooper says

Rural COVID-19 cases

While COVID-19 hit large population centers like New York early the pandemic, rural communities have their own vulnerabilities, said George Pink, deputy director of the NC Rural Health Research Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Even before the pandemic many rural health systems around the country faced financial struggles and staffing shortages, he said.

Demographics and higher uninsured rates in rural communities can put them at a disadvantage.

“Rural residents are older, sicker and poorer,” he said. “Going into COVID, those three factors alone make them more likely to get COVID, more likely to die from COVID, and it makes them more likely to require ventilation compared to more urban populations.”

A report from the NC Rural Health Research Program found rural hospitals in much of the country, including the South, have seen higher shares of COVID-19 patients among their hospitalized populations than urban hospitals.

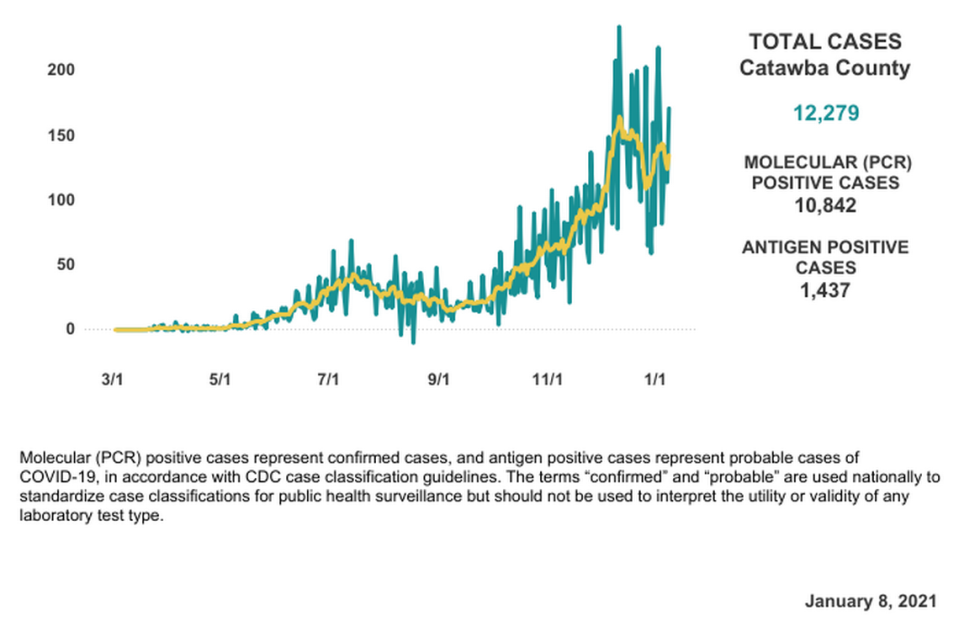

Catawba, with the largest population of the four counties home to the health systems working with the field hospital, has seen some of the highest total number of cases in this part of the state.

Like many places in North Carolina, infections initially peaked in mid-summer then slowed for much of the fall. By early December, a second surge was well underway in Catawba County and the surrounding area, a Charlotte Observer analysis of NC Department of Health and Human Services data shows.

While Catawba County has more cases overall, Caldwell County has been slightly harder hit over the last two weeks, DHHS data show. The case rate in Caldwell (number of positive COVID-19 tests for every 100,000 residents) is one of the worst in the state at 1,320, based on data from the last 14 days reported Friday by DHHS.

In both Catawba and Caldwell counties the percent of positive tests is significantly higher than the statewide average. Data from Friday showed an 18.8% positivity rate in Caldwell and 17.4% in Catawba. The statewide average was 13.9%.

The smaller counties, Burke and Watauga, have at times in recent months seen greater swings in COVID-19 caseloads but generally have recorded lower infection rates per capita in the last two weeks. Looking at Friday’s data, DHHS reported a positivity rate of 9.5% in Watauga and 11.4% in Burke.

Holzhauer, the field hospital medical director, said Samaritan’s Purse will stay as long as needed, and expects to fill all 30 beds at some point. Officials have said they expect the field hospital to be active at least four weeks, given epidemiological projections.

“The projections show cases continuing to rise until mid-February and peaking in mid-February,” Holzhauer said.

“We’re hoping that we got here just in time to relieve enough pressure so that the hospitals won’t tip over and hit that breaking point.”

‘The worst perfect storm.’ How the second COVID surge is ravaging NC nursing homes.