Inside Judy Chicago and Donald Woodman's New Mexico Art Mecca

When you set out to give the women who were largely shut out from the history of Western civilization a literal seat at the table, you need a big table. By the time Judy Chicago completed The Dinner Party, her famous installation artwork, in 1979, her triangular banquet table stretched 48 feet in each direction, big enough to accommodate a fantasy league of all-female power players: the Greek poet Sappho; suffragist Susan B. Anthony; and Elizabeth Blackwell, the first female physician in the United States.

In the 27 years since Chicago and her husband, the photographer Donald Woodman, blazed a trail to the town of Belen, New Mexico—pop. 7,152—their own, considerably more modest, dinner table has hosted its share of pilgrims. Among the signatures in their old-fashioned, ledger-style guest book (a housewarming gift from Chicago’s former literary agent) are museum directors and curators who have come to pay homage, plus old friends like Gloria Steinem and passers-through like Arnold Schwarzenegger (he was shooting a movie nearby). “People from Santa Fe view Belen much like New Yorkers see the world beyond the Hudson Valley—i.e., is there life there?” Chicago says. “We used to joke that it was easier to get visitors from China than from Santa Fe.”

Chicago and Woodman landed in Belen—Spanish for “Bethlehem,” it’s pronounced like Berlin, minus the r—a sleepy town 35 miles south of Albuquerque, for reasons familiar to most artists. For starters, Chicago says frankly, “we were broke.” The pair, who are frequent collaborators, had spent the previous eight years pouring their time and money into their sweeping multidisciplinary series the Holocaust Project. When they lost their lease in Santa Fe, Chicago wanted to go back to L.A., but Woodman put his foot down. “There was no way in hell I was going back to a big city,” he says. Like many photographers before him, he loved the wide-open spaces of New Mexico and, more to the point, the freedom of life outside a high-pressure art scene.

Belen was a thriving railroad town in the first part of the 20th century. Near its still active rail yards, they stumbled upon the Belen Hotel, a derelict former rooming house built in 1907, which is still on the National Register of Historic Places. They paid $20,000 for the building. “There wasn't a window that wasn't busted out,” Woodman recalls. “The roof leaked like a sieve.” People had inhabited the space without plumbing or electricity; drug paraphernalia was strewn throughout the building. But Woodman, who had grown up in New England, saw the romance in the building’s hulking Victorian lines.

Woodman, who started out as an architectural photographer, undertook the renovations himself. Working with preservation architects, he hired a carpenter to remove every piece of trim and woodwork that could be salvaged, then a demolition crew to strip all the old plaster. Then Woodman painstakingly put it all back together. He initially gave the project a year. As it stretched to three, and the couple kept running out of money, Chicago began to call it “Donald’s folly.” Meanwhile, she was working out of “the smallest studio I’d worked in since I was 21.”

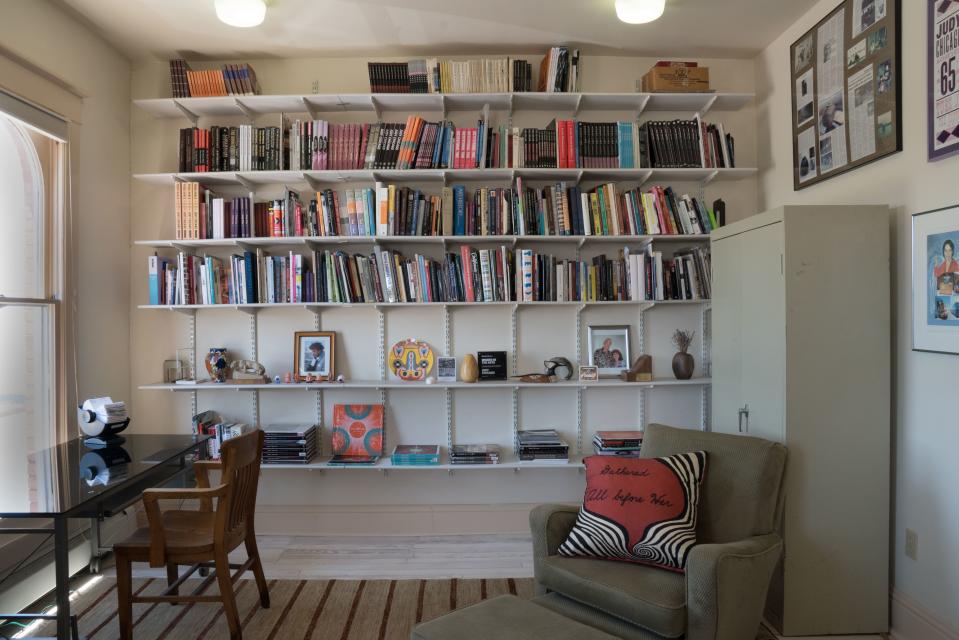

Ultimately, Chicago had to admit that Woodman had constructed the space to perfectly accommodate the way the couple lives and works. Historic preservation rules dictated that the long hallways of the boardinghouse remain; the original central staircase still bifurcates the building. In the two-story space, just 1,000 square feet are dedicated to their living quarters; the rest is divided into an apartment for guests and collaborators and parallel studios with 12-foot ceilings—hers kept rigorously tidy, his not so much.

Technically, since Woodman and Chicago had met seven times before—as Chicago puts it, they finally “ignited” in the fall of 1985—you can’t call them a love-at-first-sight story. But within a few days of their first date, they were living together. “After a week, I freaked out,” Chicago says, “thinking that things like this, falling in love this fast, don’t happen in real life.” She threw him out. But a few days later, she invited him to lunch. “I thought, Judy does not do lunch,” Woodman recalls, “so I knew this was really a special thing.” Chicago’s idea: Maybe they should give this thing a try, see if it could last. Woodman turned her down. “I went, ‘I'm not interested in a casual affair,’” he says. “Either we get married right now or forget about the whole thing.’’ As he recalls it, Chicago “turned white as a ghost, swallowed hard, and said, ‘Well, I think we should meet each other's family first.’”

That was in November; by the new year, they were married. “I can’t recommend such a rapid romance,” Chicago says, “but for us, it works.” It helped that Woodman, she says, is as much a “gender renegade” as she is. Sometimes she jokes that together, they make one perfect person.

If the pair’s decision to live off the beaten track was motivated by Woodman’s need for space, it could be said that Chicago, too, needed room—if not in the same way. For an artist whose work has been alternately revered and maligned for decades, keeping much of the world at a safe remove has its self-protective benefits. “It has been very difficult, hurtful, and isolating to have found myself the object of misunderstanding, ridicule, and suspicion,” says Chicago, whose early sculptural work is currently being shown at Jeffrey Deitch’s gallery in L.A.; come October, New York’s Salon 94 will exhibit her preparatory drawings for “The End.”

Indeed, though at the age of 80 Chicago is both Belen’s most famous resident and a veritable deity in the art world at large, her work—and the fact that it deals with the female body—can still set conservative teeth on edge. Several years ago, when Woodman and Chicago announced their intention to build upon Through the Flower, the educational nonprofit they’ve operated for some 40 years, by opening a gallery of the same name in Belen, local Christian fundamentalists mobilized to put a stop to it, decrying the sexual themes in Chicago’s art.

Today, Chicago refers to it as the “Belen brouhaha.” That was painful, she says, but the negativity has since been “completely overshadowed” by the outpouring of support from other members of the community—including Belen’s young mayor, who pledged to donate his annual part-time salary to the space.

It’s too soon to say whether the small art space they recently debuted will do for Belen what Donald Judd has done for Marfa in West Texas—creating an art destination in the midst of the tumbleweeds—but by late summer, Chicago reported that guests were spending hours at a time in the gallery. “On a Wednesday afternoon to get 20 visitors in a small rural community?” Woodman says. “It’s amazing.”

Originally Appeared on Architectural Digest