An Inside Look at Chicago’s Seedy Car-Impound Netherworld

"It's a Fleetwood Brougham," says Spencer Byrd, now 51, about his 1996 Cadillac. "It's got the LT1 engine in it. Positraction, everything. The last full-size Cadillac, and it had only 120,000 miles on it. They get confused, saying, 'Blue Book value says it's only worth $1600.' But if you wanted to go buy one, you'd be paying $4500 to $5000."

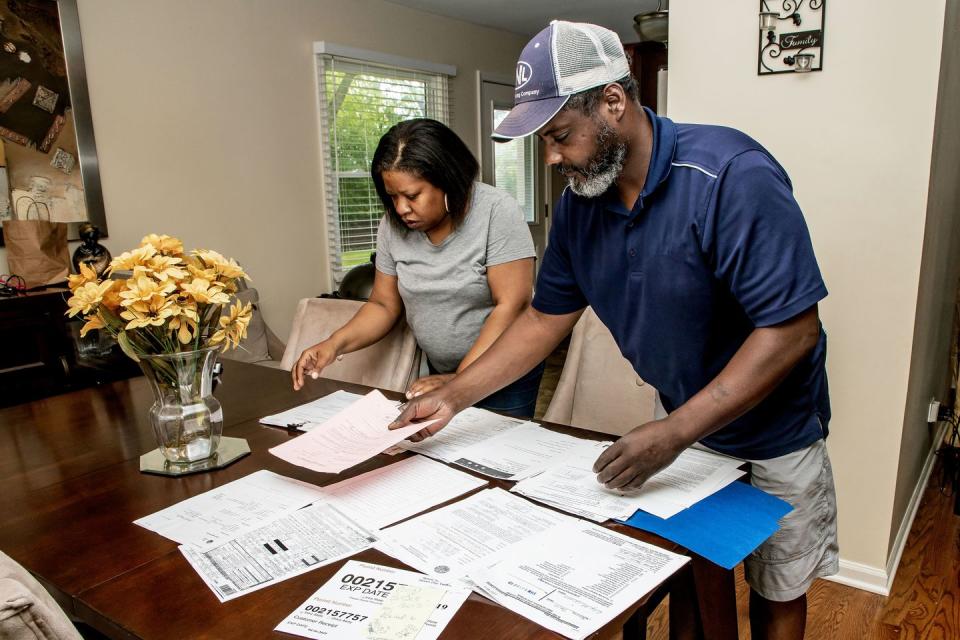

Byrd's Caddy was impounded in 2016 when he was stopped in Chicago for a malfunctioning turn signal and his passenger, a man who had hired Byrd to fix his car, was found to be carrying heroin. Byrd himself wasn't charged with a crime. Even though a judge ruled his Cadillac should be returned to him, there's a $17,000-plus lien against it to cover towing and storage charges. The impound yard hasn't let him pull his tools out of the trunk—tools he uses to make much of his living as a part-time freelance mechanic. And Byrd doesn't believe his turn signal was broken anyhow.

Impound in Chicago is the automotive netherworld, an opaque labyrinth where bureaucratic inertia separates cars from their owners. It's a system so densely packed with obscure rules that it can take vehicles from even the innocent, never to be seen again—at least not by their rightful owners. Chicago's system is radical, but impound is a problematic thing around the country. Issues range from strict time limitations for retrieving your car in Los Angeles to allegedly corrupt towing companies in Detroit.

"Everybody, at one point or another, has dealt with this," explains Elliott Ramos, a reporter with WBEZ radio, Chicago's NPR affiliate. "People will joke that you're not a true Chicagoan until you've been towed. It's so aggressive, it's sort of baked into the city lore."

For those with means, when their car falls to the impound hook, the remedy is obvious. Go pay the towing charge, the storage fees, and any fines and get the car back as quickly as possible. But not everyone has the means. And for those without, a vehicle is often an even more vital element in managing their livings and lives.

How Impounding Works in Chicago

In Chicago, bureaucracy is a no-pads, full-contact sport, and the relationship between the police and much of the citizenry has long been fraught with tension. And the impound policy can feed that tension. Cars may be seized by police if they are used to commit an offense, including serious crimes like drug dealing and robbery as well as transgressions such as DUIs, street racing, solicitation, and possession. And if a car is blocking a fire hydrant or double-parked, it's considered a hazard and moved. But cars have also been towed for much smaller infractions, like littering and playing loud music. Or they're taken off the street for violating the winter parking ban, whether or not there is snow to be cleared.

WBEZ's Ramos, using notes and data from several Illinois agencies and departments, says that during 2017, the city impounded 93,857 vehicles and sold about 24,000 of them. These usually aren't high-value Porsches and BMWs, but more ordinary machinery. The longtime contractor running the program, United Road Towing (URT), manages the city-owned impound lots, tows the cars, and ultimately pays the city an average of less than $200 for each vehicle it keeps.

That amount is based on scrap value, and many of the cars are truly close to scrap. But a 2016 Ford Mustang GT went to URT in 2017 for $176, and the occasional late-model Audi or Mercedes meets its assumed doom for similar peanuts. URT keeps the profits as partial payment for administering the program. And given the true value of some of the cars, even with salvage titles, those profits could be huge.

In May 2018, after her husband Jerome was in a minor wreck, Veronica Walker-Davis, 51, a nurse on disability, had her 2006 Lexus ES330 towed to a shop in Chicago to be repaired. It was taking a long time to be fixed. The shop kept claiming they were waiting on parts, she says. She now believes they were lying.

"Apparently, someone in the shop drove my vehicle," she says. "He was pulled over by the police. He had a revoked driver's license, and they impounded my car. My car was impounded on June 3, and I found out it was in the pound on June 23." Fees were already accumulating. "By the time I found it, the fees were $2500," she sighs.

According to WBEZ's data analysis and reporting, driving with a suspended or revoked license is the most common offense cited for Chicago's impounding. And for many drivers without the resources to pay traffic fines, that can arise from accumulated ticket debt. But Walker-Davis didn't have a suspended license. She wasn't in or near the car and had not given the okay for this employee to drive it.

"I haven't been able to acquire another car," rues Walker-Davis. She's been relying on friends and family to shuttle her to doctors' appointments for the last year.

The Fees Accumulate Fast

Photography on the ground can't capture the scale of the Chicago Auto Pound at 701 North Sacramento Boulevard in the West Side's Humboldt Park neighborhood. But it's there on Google Earth, an elongated triangle nestled between the Union Pacific tracks of two marshaling yards for the Metra commuter-rail system. If you're there to retrieve a vehicle, wear comfortable shoes. The lot is more than a half-mile long; you'll be on a hike. And that's just one of five auto pounds around the city.

Chicago's system exists in an alternate universe outside the criminal-justice realm. As soon as a car is impounded, it begins accruing towing, administrative, and storage fees that must be paid before a final judgment is rendered about the legitimacy of the city's action. The city has up to 10 days to send out an impound notice to the car's owner (though nothing was sent to Walker-Davis). And the hoops that an owner must jump through include making a request for an administrative hearing in person at the Department of Administrative Hearings within 15 days of the notice's postmarked date. Between 2001 and 2017, vehicle owners failed to request hearings in more than half the 200,000 cases. If an owner fails to do so, he or she is still responsible, as Walker-Davis was, for an administrative penalty, towing fee, and storage costs. But at that point, the city is free to dispose of the car as it sees fit, be that selling it at auction, scrapping it, or keeping it for police use.

A Civil Matter

Given this is a civil matter, not a criminal one, vehicle owners who cannot afford representation by an attorney will not be granted one for the administrative hearing. So if they make it to that point, many find themselves alone in a small, stark room facing obscure laws and a city attorney acting as an administrative-law judge. And Chicago doesn't accept an "innocent owner defense" in impound cases.

The libertarian Institute for Justice (IJ), a Virginia-based advocacy law firm that argued the landmark 2005 Kelo v. City of New Londoneminent-domain case before the Supreme Court, has taken up the Walker-Davises' cause.

"The Davises went to that hearing on July 12, 2018, and explained what had happened," says Diana Simpson, their IJ attorney. "And the judge basically said, 'Well, too bad. You can't use your defense to get out of this.' So they have to pay the administrative penalty, which is $1000 for operating the vehicle with a suspended license, and then on top of that, they have to pay the towing and storage fee." But with the help of the pro bono attorney, they appealed to the Circuit Court of Cook County. And on January 7, the Walker-Davises entered into an agreement with the city to get the car back for $1170—a compromise, as long as they picked up the car by March 31. That was a Sunday.

"So Veronica went on Monday, the very next day, to pay the money," Simpson continues. "But the city wouldn't take the money because the registration had lapsed while it was in the pound. So she went to the Secretary of State's office to update the registration, but it had already closed. The next day, April 2, she was able to pay the registration and get the city to extend the deadline to April 12. On April 10, she went to pay and everything should have been fine. But she found out the city had disposed of the car on April 3."

Where is the Lexus now?

So far, no one seems or claims to know. Even if the city does know where the car is, and even with a state order to return the Lexus to the Walker-Davises, the city doesn't have to. A referendum passed by Illinois voters in 1970 amended the state constitution to empower counties and cities with populations of more than 25,000 to impose and enforce their own taxes and penalties, giving Chicago the power to ignore certain state court orders.

Chicago's government is perpetually short of money. It was big news last year when the city's structural deficit came in at only $98 million. "In 2012, our structural budget deficit was $635 million and all four of Chicago's pension funds were on the road to insolvency," then-mayor Rahm Emanuel said in July 2018. "Today, the city's finances are in a much different place." To get to that place, the city raised property taxes and imposed new taxes on everything from water and sewage use to Uber and Lyft rides. The sheer misery of the impound system could be understood in the context of that drive for revenue. Understood, but not excused.

Chicago isn't making much money on these impounds. Again according to WBEZ's Ramos, the city generated $27 million in revenue from fees and scrap sales to URT during 2017. But it cost more than $22 million to administer the program. And determining that figure meant spelunking through reams of data from different agencies that don't necessarily communicate with one another. The total net for the city was about $4.6 million—chump change in light of the city's ongoing and projected fiscal disasters.

It's Chicago's poorer and minority populations that get socked by the impound racket. And the defense of it mounted by the city seems halfhearted at best. URT hasn't responded to an inquiry from C/D and hasn't replied to WBEZ's many requests for comment.

What happened to Byrd and Walker-Davis isn't unique. They are simply the best publicized cases. And that publicity has caught the attention of groups from across the political spectrum. The American Civil Liberties Union, other civil-rights organizations, and anti-taxation groups hate the system. The IJ's representation of the Walker-Davises has morphed into a class-action lawsuit on the constitutional grounds that the government can't punish the innocent or confiscate property without good reason.

Chicago Alderman Gilbert Villegas proposed regulations last year that would modify the city's impound system, cap and reduce some fees, and offer community service as an alternative to fines. "Our intent shouldn't be to bankrupt a family that's trying to live within the city of Chicago," Villegas told ProPublica. Despite support from other aldermen, so far nothing has been enacted. But with new mayor Lori Lightfoot and with Villegas's ascension to the chair of the Committee on Economic, Capital, and Technology Development, the legislation is still alive.

"I was totally exonerated of everything," says Byrd. "Once I got out of court, I should have been able to go to the city of Chicago, get my keys, and get my car. That's how it should have gone. The state courts waived the storage fees. The city of Chicago overruled the state."

The Government Wants Your Stuff

There's no question that on May 22, 2013, Tyson Timbs sold $260 worth of heroin to an undercover police officer. He pleaded guilty to one criminal count for the incident, which took place in Grant County, Indiana. And then the state took his $42,000 2012 Land Rover LR2.

Asset forfeiture is the kissing cousin of impound. It allows law enforcement agencies to seize property from criminals or suspects. But also from people who are completely innocent. Innocent like Jennifer Boatright and Ron Henderson, a Houston couple crossing Texas in 2007 who had $6037 with them to buy a used car. They were stopped in the small town of Tenaha, and the police searched their car. The officers found the money and an unused glass pipe and took the couple to the police station where they were offered a choice: They could be charged and their children taken into protective custody, or they could fork over the cash.

As a law enforcement tool, forfeiture can be an effective way of stopping criminal activity. Seizing Al Qaeda's assets before it can perpetrate another terrorist plot is a good idea. But it also incentivizes the agencies involved to seek out tasty things to take.

The ACLU of New Jersey issued a report last year tracking seizures between January and May 2016. Assets totaling $5.5 million were seized in New Jersey during that period, with every county participating at some level. Newton, a town with a population of 7960 at the last census, took $660,025 worth of stuff alone. Most often, the assets became the property of the municipal, state, or federal law enforcement agencies that did the taking.

Boatright and Henderson fought their case until it became a class-action suit brought by the ACLU against Tenaha and Shelby County. From 2006 to 2008, those governments had seized about $3 million from at least 140 people, according to the ACLU. And none of those people had been arrested or charged, just stopped and shaken down. In 2012, that case was settled and the abuse was shut down.

Timbs's case wound through the judicial system until last year when it reached the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS). There, in a landmark, unanimous decision written by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, SCOTUS overruled the Indiana courts and held that the Eighth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution's prohibition against excessive fines applies to asset-forfeiture cases. After all, Timbs's Land Rover LR2 was worth about four times the maximum $10,000 fine for the crime. Expect at least some changes in light of this decision.

From the August 2019 issue.

You Might Also Like