Inside South Africa's Illegal Street Racing Scene

It is a late afternoon in Sea Point, a suburb of Cape Town, South Africa, and one by one the cars roll into the Queen’s Beach parking lot. Toyota Corollas, Honda Civics, BMW 318s and M3s, Audi Quattros and Volkswagen Golf Mk 6, 7, and 7.5s. Models range from the mid-Eighties to the modern-day showroom in colors of Midnight black, Porcelain white, Platinum silver and Vermillion red. There are lowered suspensions, hidden turbochargers, modified engine control units, gleaming exhausts, hood scoops, rear spoilers, tinted windows, and engines with baritone growls or mezzo-soprano screams. As the asphalt lot fills, it becomes readily clear that the cars are all built for one purpose: speed.

But nobody drives faster than a crawl. On this speck of Cape Town’s coastline, the car owners have come for their Sunday “cool-down.” It’s a weekly tradition where locals smoke hookahs, puff joints, and sip beers. Who could blame them? Here—the virtual bottom of the world—the view is breathtaking. Waves crash onto the rocks, water stretches out endlessly, and a pink-orange sunset spreads over the horizon like neon cake frosting.

Yet as the last light fades, the mood takes a turn. The energy amps up. Because for many of these car owners, weekends in Cape Town are about racing. Illegal racing. “There is a massive car culture here,” says Junaid Hamid, a former street racer turned private driving instructor. From blazing through traffic on the N1 motorway to drag racing (a.k.a. “robot racing”) along Strandfontein Road, Cape Town has more than thirty hotspots that fire up on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday nights.

By midnight, the denizens of the Queen’s Beach parking lot have reconvened at a Shell station on Sable Road. With forty cars parked bumper-to-bumper, the theatrics begin. Posturing. Boasting. Trash talking. Finally, a challenge is thrown down between two drivers—a run on the N1, a national highway that originates in downtown Cape Town and stretches clear to the border of Zimbabwe—heavily traveled in Cape Town by day, relatively empty by night. Everyone jumps into their cars to watch the action.

For others, mired in poverty, crime, and hopelessness, racing means freedom and a small way to give their lives meaning.

As the Shell station empties out, it’s clear that despite their differences of race, religion, and economics, these competitors all have at least one common strand in their DNA. They all know the risks. Crashes. Hospital visits. Body bags. Not to mention the infamous Ghost Squad, Cape Town’s task force designated to lock up the turbocharged outlaws.

But the young men disregard the danger and consequences. The reasons they race are as diverse and complex as South Africa itself. For those with jobs and expendable cash, they do it for street cred or for the rush. For others, mired in poverty, crime, and hopelessness, racing means freedom and a small way to give their lives meaning.

The suburb of Maitland lies to the east of central Cape Town. There is nothing picturesque here. Factories, machine shops, and warehouses line the streets of this industrial neighborhood. A garage called Performance Solutions sits near the end of a narrow block. It doesn’t look like much: a simple blue-and-white sign above a concrete space that fits little more than a single car. But street racers across the Western Cape, those with enough money and connections, know that the nondescript shop is the place.

One afternoon, a 38-year-old named Naseem (who goes only by first name) stands on the sidewalk out front. Sinewy, with close-cropped hair, he wears jeans, a black T-shirt, and sneakers. Naseem is of mixed race. When he speaks it’s with a thick accent, a mix of English and Afrikaans.

“That’s my car,” says Naseem, pointing to the black 2001 soft-top M3 in the Performance Solutions garage. He bought the car in January 2019, and he street races when the BMW hasn’t been in the shop for body work (he flipped it) or rear suspension issues. “It’s a hobby,” he says. A hobby that’s gotten him locked up twice by the Ghost Squad.

Naseem's construction gig pays well enough that he’s swapped out his BMW engine for a Toyota Supra 2JZ-GTE twin-turbocharged 3.0 liter inline-six. The swap cost him 30,000 South African Rand (about $1700), but he happily paid up, as the 2JZ is akin to a Holy Grail. (“Two-jay-zee engine, no shit,” said Jesse, the character played by Chad Lindberg in the original The Fast and the Furious. “This will decimate all.”) The 2JZ is renowned for its strength. But what makes the engine legendary is that in the hands of the right tuner it will transform a car from something special to something spectacular.

That’s why Naseem has come to Maitland. “I’m not a mechanic,” he admits. “So when I do something I take it to the right people.” By “right people,” Naseem means Seraaj Rylands, owner of Performance Solutions. The 45-year-old is the Michelangelo of Cape Town tuners, the Jedi master, a man known to create art and magic under the hood. “He’s the most hated guy because he’s the right guy,” laughs Naseem. “They all want to kick his ass.”

Born and raised in Cape Town, Rylands started racing in high school. Every night he’d go out in his modified little Toyota Corolla looking to test the car’s limits. To test his own. Rylands tells a story from the early 2000s when he came across a E46 BMW M3. “It was a new car on the road,” he says. “I just wanted to race with that.” The two drivers went to Pinelands, another eastern Cape Town suburb. Rylands edged the Bimmer in their first run on the N2, and it was such a thrill that the two men wound up racing over and over until they had no fuel left. “That was raw fun,” he recalls.

Rylands stopped “real” racing a decade ago and focuses on the 20 or so clients he calls his “family.” They range from guys like Naseem, trying to squeeze some more power out of an engine for a reasonable cost, to a Toyota Supra owner who “wanted the best of everything no matter the cost,” Rylands explains, which included a 50,000 Rand (about $2900) intake manifold, a high-performance exhaust, custom carbon-fiber parts, and a turbocharger. “I built it four years ago,” Rylands says of this Toyota. “It was the second fastest car in Cape Town.”

Naseem and Rylands discuss the M3. According to the dynamometer (impressively, Rylands has one crammed into his tiny shop), the engine is currently putting out about 450 hp. But Naseem craves more. The tuner isn’t precisely sure how much more he can crank out of the 2JZ, but he knows he will get something. The M3 will be faster. Naseem is pleased yet still, he explains, anxious. Not about Rylands’ abilities, but about how fast he can get it done. “I hope he can have it by Saturday,” says Naseem. “It’s my favorite night to race.”

January 26, 2019. On this warm, cloudless Saturday night, the scene at the Sable Road Shell station got going early, wall to wall with the usual Golfs and Quattros and BMWs, not to mention a few big dogs: a Porsche GT3, a Benz V-12, a McLaren. The Botha brothers—Tyran, 22, and Dean, 21—and their pal Merlin Peterson, 21, were particularly amped because Tyran’s 318i had just gotten tuned. “Everyone pulled up that night expected good races,” says Dean, looking back on it. “No one expected that accident.”

They expected good races because Taufiq Carr was there in his BMW M3. The 26-year-old was fast and fearless. The King of Sable Road, as he called himself, had come that night with his wife, Ameerah, and two children. “She wanted to race with him,” recalls Dean. “He said, ‘hell no.’”

The first time that Taufiq ran the N1 that night, the King of Sable Road strengthened his street cred. “Taufiq didn’t just beat the guy,” explains Tyran. “He destroyed him.” Customarily, drivers meet their friends on the bridge after the race. But Taufiq didn’t show, which only meant one thing: the drivers were going to run it again.

The second time, Taufiq was smoking his competition again. Yet as the two racers neared the Sable Road overpass, Taufiq’s M3 suddenly wobbled, then slid across three northbound N1 lanes, hit a barricade, went airborne, slammed into the underside of the bridge, and wound up in the far lane of the southbound N1. “It felt like an earthquake,” says Tyran. “The whole bridge vibrated and there was dust, debris, and then you saw the car on the other side of the highway.”

By some miracle, there weren’t any southbound cars in the vicinity on the N1 at that moment. But the King of Sable Road was still in trouble. He used the voice command feature of his BMW to call for help. He later described the moment from his hospital bed: “I looked down into a pool of blood. There was just blood gushing out of my legs, like a tap that was turned open.” While Taufiq survived, his legs did not. They were amputated. The entire incident might have wound up as no more than a story in the local newspapers if not for two videos of the horrific crash. One was shot from the Sable Road overpass, the other from the inside of Taufiq’s car, courtesy of Imraan Ebrahim, who was in the car and somehow walked away unscathed. The videos surfaced almost immediately and went viral. Illegal street racing became the talk of Cape Town. Editorials were penned. Television news stories were produced.

City officials vowed to crack down harshly. One would think the violent crash and the aftermath would put a damper on the racing scene. Did it? “It doesn’t appear so,” admits Alderman JP Smith, who serves on the Cape Town mayoral committee on Safety and Security. “It is still alive and well.”

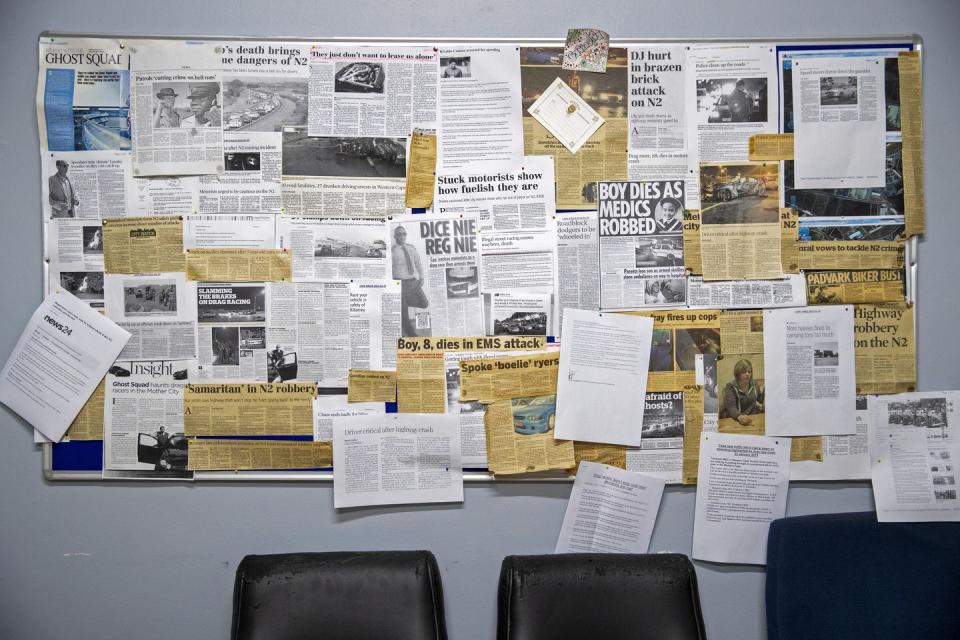

In a small, windowless conference room on the ground floor of the Gallows Hill Traffic Department in the Green Point suburb of Cape Town, a bulletin board hangs from a wall. Every inch of the board is covered in Cape Town newspaper clippings, and the headlines reveal a consistent theme: “Slamming the Brakes on Drag Racing.” “Driver Critical after Highway Crash.” “Ghost Squad Haunts Drag Racers in the Mother City.”

The Ghost Squad. It’s a name that strikes fear in the heart of any illegal Cape Town street racer. As well it should. Tonight, a little before 8 p.m., the squad of police officers gathers in a parking lot at the back of the Traffic Department building for their pre-shift briefing. Here at their de-facto Hall of Justice, they dress in light and dark blue pants, vests, jackets, and shirts with purple shoulder patches. They talk amongst themselves, occasionally smile, but the mood is serious, as every night they’re on the job is another night they might not come home.

Founded in 2009, the Ghost Squad originally consisted of twelve officers with one goal: making the streets safer. Their secret weapon? Unmarked police cars, which until that point had never been used in Cape Town. (That is why they call themselves the Ghost Squad; they lurk on highways, unseen.) Today the Ghost Squad has nearly doubled in size. Their thirty-plus vehicle fleet—some of which have engines modified for speed—features Golfs, Opels, Lexuses and Honda motorcycles. While they now average 8,000 traffic offenses a month (a 400 percent increase from the squad’s inception) their real goal is shutting down guys like Naseem and Taufiq. “Drag racing became the specific target of the squad,” explains JP Smith. “They generate more complaints than most.”

Smith knows of what he speaks because he’s responsible for the Ghost Squad. “That’s my baby,” he says proudly. If the officers are akin to Wild-West deputies chasing outlaws, then the tall and blond-haired Smith is Wyatt Earp. He is confident, fearless, and respected. “He is the boss of Cape Town,” says one street racer. Like Earp, Smith was also once an outlaw himself. “When I was younger and more reckless I was not committed to holding up the law,” he says in his Afrikaans accent. “I used to go with my brother onto the freeways at one o’clock in the morning. I used to grieve for guys when the Traffic Department got them. Now it’s my duty to get them.”

Getting them, according to Smith, remains a constant cat-and-mouse game. Still, the line between the good guys and the bad guys is not always so clear. There are stories of these officers pushing the boundaries of the law. Former street racer Junaid Hamid recalls a night driving home from an event at Killarney International Raceway. Although the sports car Hamid drove had a flashy rear wing and no roof, it was completely street legal, and he wasn’t speeding. “I saw a guy in a Lexus start following me,” recalls Hamid. “Then he pulled up next to me, going forward and backward, forwards and backward, trying to get me to race.” As he looked closer, Hamid noticed a jacket covering a uniform—a Ghost Squad uniform. “He tried to entrap me the whole way!” exclaims Hamid. “About five minutes from my house he pulled me over and gave me a fine. But if I’d raced him, he would have arrested me and impounded the car.”

“If your car breaks down, and you’re alone, they’ll fuck you up. Steal your car. In that moment sometimes you’re glad to see the Ghost Squad.”

The Ghost Squad has even busted some of their own. Three years ago a trio was caught racing along the N7 motorway. The culprits? Two traffic officers and a firefighter. While not a common occurrence, the bust wasn’t an aberration, either. “They are all people and have their own predilections,” says Smith. “They don’t suddenly become automatons because they join law enforcement.”

On some occasions, according to Naseem, the Ghost Squad is actually a welcome sight. Most drivers and spectators in the racing scene embrace outlaw culture only when it comes to speed. But not everyone. “Some guys at races come to sell drugs. Some will rob you. That’s how it goes here,” Naseem says. You have to keep your head up at all times, he notes, especially in the wee hours of the morning. “If your car breaks down, and you’re alone, they’ll fuck you up. Steal your car. In that moment sometimes you’re glad to see the Ghost Squad.”

A group of gearheads loiters in front of a garage in Hanover Park, a township in the Cape Flats region southwest of central Cape Town. Performance Solutions is a NASA lab compared to this place. The cramped, dank space is littered with grease stains, tires, and aging car parts. A sign reads: “Tyre Shop: Contact Nur.” The owner, Nur, who specializes in tire repair, laughs about the Ghost Squad. How they target modified cars even when they’re not racing. How they confiscate drivers’ discs—the South African version of a vehicle registration—for what they claim are infractions like lowered suspensions or windows overly tinted. “What the fuck?” Nur’s bulbous belly jiggles. “It’s how they make money.”

Money. It’s something scarce in Hanover Park. In the 1950s the apartheid government enacted the Group Areas Act, a race-based law that forced non-whites out of central Cape Town. Tens of thousands were relocated to housing projects in Cape Flats. Post-apartheid, the conditions remain bleak. Unemployment hovers well above 50 percent. Instead of condos and Walmarts, the local conglomerates are gangs like the Hustlers, Rude Boys, and Americans. After a July 2019 weekend that saw 73 murders, South Africa’s president, Cyril Ramaphosa, sent the military into parts of Cape Flats to quell the violence that has made Cape Town the 11th most dangerous city in the world, according to USA Today.

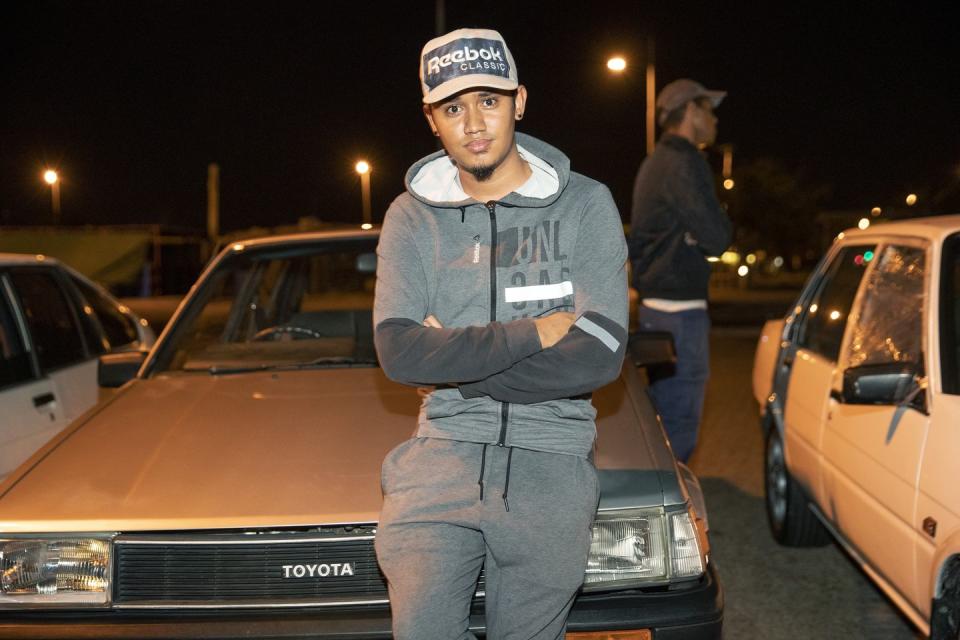

Yet in Cape Flats, a street-racing culture still thrives. It’s not about turbochargers or custom intake manifolds. It’s about passion. Example A? The white 2007 Toyota Corolla in Nur’s garage. It belongs to Ishmaeel, his younger brother, who bought it bare bones. Over the past four years, he’s rebuilt it “sticky-sticky,” as he describes, meaning slowly, piece by piece. Currently out of commission since a taxi rear-ended it, that car is still basically just two front seats, an engine, four wheels, and some wiring. It looks more like something that should be on blocks on a front lawn. But Ishmaeel regards it like a Maybach.

“It’s a 20-valve Toyota engine,” boasts the 28 year-old. “I lowered it in with my own two hands.” Leaner than his brother, he sports a black Kanye West T-shirt, stone washed jean shorts, and Pumas. He dreams of converting the car to a soft-top, making it all-wheel drive, and getting a 2JZ engine, but without a job, reality means working with what he has now.

He fell in love with cars at the age of 12 when his grandfather Muhammad had Ishmaeel drive him to the airport in his Toyota Cressida. “He told me ‘Don’t be afraid of the next car. If he comes to you just bump him,’” recalls Ishmaeel. “I just stayed in my lane, dropped him off and came back home. After that I drove my dad’s car everywhere.” He went to drag races at the track, watched drifting, practiced burnouts, and by 16 he was building his own stuff. No instructional books, no Chip Foose videos, no mentor. It was all self-taught, trial and error.

For Ishmaeel cars were more than just a hobby. They were an escape. Under the hood he could forget about the drive-by shootings, the opportunities that didn’t exist. He was no longer a poor kid from Hanover Park; he was a mechanic, a racer, he had a skill and talent that he could show on the streets of Cape Town. If he could create a car from nothing, a fast car, then maybe anything was possible.

He and his buddy Maekaeel race as often as possible. “It depends where the cops chase us,” Ishmaeel laughs as he sucks on a Pall Mall. He’s not alone. There are groups of friends who all drive German or Japanese cars. Crews with names “Midnight Racing” and “Racehorse.” He refers to local legends like Wasef in his matte-black Golf, and Suspect, the former street racer who earned his moniker because he did so well for himself with his bread delivery business that people assumed he had to be selling drugs.

There are no pink slips or cash on the line when Ishmaeel and his friends take to the streets. It’s not about status. It’s a “normal hobby,” as he puts it, but one Ishmaeel cannot live without. “We race every day,” he says. “We don’t know when and where. It just happens.”

On a cool, breezy Sunday, thousands of Capetonians pour into the Killarney International Raceway complex for Bragging Rights CPT (the CPT stands for Cape Town), a daylong auto event presented by the Western Province Motor Club. The tar oval section of the track is dedicated to Pro-Am drifting. “Show & Shine,” an auto show, lets fans get up close with pristine custom, stance, and hot-rod builds. On Killarney's backstretch, 67 dragsters from across the Western Cape and Johannesburg are facing off in the quarter-mile, teams with names like Bogeyman, Killer B, Megatron, and Menace II Society. Suspect is here, and so is Seraaj Rylands. All the racetrack sensory pleasures are to be found: the smell of gasoline and scorched rubber, the thunder of engines throttling. The crowd is overwhelmingly male, guys in shorts, baseball hats, and sunglasses, smoking hookahs and barbecuing.

Ghost Squad cops are here, too, as is Wyatt Earp himself, JP Smith, glad-handing and chatting up familiar faces. The two worlds—the law and the law-breakers—amicably mingle today, but Smith hopes for more than a moment of shared passion. He seeks a long-lasting reconciliation much like the one South Africa itself went through in the Nineties when apartheid collapsed.

All the racetrack sensory pleasures are to be found: the smell of gasoline and scorched rubber, the thunder of engines throttling.

The alderman believes that the seeds have been planted here at Killarney International Raceway. “A few years ago I got in a discussion with some guys in the street scene,” he explains. An alternative was proposed. In March 2016, Killarney began hosting robot racing. Every Sunday night, weather permitting, anyone can pay 70 Rand (about $4) to drag race his or her car on the same asphalt where F1 legend Sir Stirling Moss once competed. “It attracts 300 cars and 5000 people on a good night,” says Smith. “We’re trying to make as many legal opportunities as possible.” There’s been talk of extending the track to build a longer runoff, subsidizing entry fees, and bumping up robot racing to twice a week.

Substituting the track for the street makes total sense. Medical personnel on hand. No unexpected traffic or pedestrians or Ghost Squad to worry about. The crowds packing the blue-and-white grandstands along the backstretch starting line are far more than could ever cram onto the Sable Road overpass.

Still, drivers like the Botha brothers contend that robot racing isn’t the Mecca that lawmakers make it out to be. “It’s pricey,” says Dean. “We don’t want to have to pay.”

“There are a limited amount of races,” adds Tyran.

The two also claim the track is too narrow, that the cars are required to line up too close to each other, that the asphalt has perilous uneven patches. But a more likely reason the Bothas and the still-thriving street racing culture hasn’t converted to robot racing at Killarney is the very essence of what it means to be an outlaw. Freedom, thrills, risk. Defining life on their terms, no matter the cost. “Some people just enjoy being on the street scene,” admits Smith. “Being chased by the traffic department.”

Around 4 p.m., Bragging Rights CPT comes to a close with the final drag race. Because team Suspect suffered engine problems, the bragging rights on this day belong to local Ralph Kumbier, with a time of 8.9 seconds in his Chevy Camaro. Gradually, the sea of spectators and teams clears out of the racetrack grounds, and finally there is silence. But it will not last. In a few hours, with dusk turning to night, the engines will once again fire up across the city as drivers race through the streets. It is, after all, Sunday in Cape Town.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos