The Inside Story of Formula 1's Coronavirus Collapse

I got this text on Tuesday, March 3rd:

Can you go to Kannapolis, North Carolina, on Thursday and then Melbourne, Australia, the weekend of 3/15 to do a 3500-word feature on Haas F1’s do-or-die season?

I’ve been a fan of Formula 1 for more than a decade. I’ve been a journalist—a career blend of sports and technology—for more than two decades. But I’d never been to a Formula 1 race. I’d never even seen a running F1 car.

There was only one answer to that text: Hell, yes!

Haas is probably the most interesting team in Formula 1. First off, it’s the only U.S.-owned team. And while the European outfits that dominate F1—massive shops like Mercedes, Ferrari, and Red Bull Racing—come to the track with massive budgets approaching $500 million a year, Haas typically spends around $175 million.

This makes sense if you’re familiar with team owner Gene Haas. The archetype of an American businessman, he turned what was a small machine shop in the 1980s into a billion-dollar business, the largest producer of machine tools in the U.S. And he didn’t come to the F1 grid as a racing novice; he’s won two NASCAR Cup championships with the team he founded in 2002.

Haas hired Guenther Steiner, a German-speaking Italian who had worked for several F1 teams in the past, as the team principal for his American outfit. Team principal is the F1 equivalent of the general manager in U.S. sports; Steiner is ultimately responsible for the team’s performance and its budget. So when Steiner approached him, Haas hunkered down with Formula 1’s 150 pages of technical regulations and emerged with a very different way of running a team.

Traditionally, F1 teams build almost everything themselves. They might buy an engine from one of the big brands like Ferrari or Renault, but otherwise they rarely even buy a bolt off the shelf. However, the rules allow them to purchase more parts than that and to work with third-parties for things like the chassis. Steiner decided to buy or commission as many parts as the rules would allow, in order to save on building out a massive manufacturing operation.

The approach was controversial. Especially since it worked. The team finished eighth in the constructor standings in its first two seasons, followed by a stunning fifth place in 2018. The small, penurious squad was beating competitors whose budgets lapped theirs by 50 percent or more. This equates to more than bragging rights; Formula 1 teams get a payout based on their standings in the championship. Finishing fifth in 2018 was worth about $15 million more to the team than its previous eighth place.

So you can understand the strong sense of optimism with which Haas started the 2019 season. And at first, the car seemed quite fast. But the team faced conflicting and confusing data: The car would be great in qualifying and then unable to find that same speed in the race. Drivers reported that it was unpredictable and unstable.

The season fell apart. Haas finished 2019 in ninth place, its worst year ever. They started with the goal of claiming fourth place and ended with profound questions about their future. The trend did not portend a bright outlook.

Those questions only intensified after Gene Haas gave a pessimistic interview at the start of March, 2020, just as the phrase “novel coronavirus” began appearing in every conversation around the planet—especially in Italy. “I’m just kind of waiting to see how this season starts off,” Haas said to motorsport.com.

Haas was weighing the benefits to his broader business with the cost of competing in F1 as a small team. “It’s definitely not financially worth it,” he said. “At least in our condition, you’re only paid about a third of what it actually costs to run a team.” It was a calculation of risk and reward: What did Haas stand to gain from a successful season, and how much would another bad season damage his finances?

Formula 1 is a world built on rigorous decision-making and ruthless efficiency, all in service of speed. Life on an F1 track is quicker than anything else most of us can imagine.

Outside of Formula 1, quick is a cute, non-threatening word. A weekend getaway is quick. A brown fox is quick when you’re practicing typing. In the F1 paddock, quick is something completely different: It’s when everything from your reflexes to your team to the weather to the hand of luck gels to make you fast on the track. In the highest form of racing, quick is something to be desired—and feared.

At the start of March 2020, everyone’s life was about to become quick, moving at a disorienting pace and testing our own reaction times and intellects and ability to balance risk and reward.

I really wanted to go to Australia. F1 is the most popular motorsport series in the world, but it’s never broken through in the U.S. I’ve been a fan for a decade, watching broadcasts at odd hours of the night from the other side of the world and then hopping on Twitter to read the latest.

This was my chance.

To: Editors

From: Mark

Sunday March 8, 1:32 PM EDT

Can we hop on the phone at some point tomorrow to discuss the latest?

I’m sure you’ve been following the news, and right now the race is scheduled to go on. But with the new travel restrictions in Italy, I still think there’s gonna be a lot of pressure on the organizers to perhaps cancel the race.

And, speaking candidly, I have some concerned folks on the homefront about my travel. The situation seems to change all the time, and is very fluid.

Let me know if there’s a good time to talk.

M

My fear was, of course, the spread of COVID-19. I wasn’t worried so much about things in Australia—at the start of March the country had fewer than 50 cases. I was worried about Italy, where the virus was raging. Two Formula 1 teams, including mighty Ferrari, are based there, as is the series’ tire provider, Pirelli. Would those outfits make it? Would they bring disease with them?

On March 8, the day I wrote that concerned email to my editors, the Italian government restricted all travel in the northern part of the country, which included the Ferrari headquarters in Maranello and Pirelli’s in Milan. Exceptions were being made for F1 personnel to get to Australia—there are few forces more powerful in Italy than racing—but there was mounting worldwide discussion about the wisdom of holding the race.

That’s what prompted my email. My editors and I talked through the situation on Monday morning. We tried to brainstorm various ways to be safe, and they told me it was my call.

I didn’t have any idea how to evaluate the risks of the trip, or how to balance them against my desire to go. I went to the CDC website and didn’t find any clear guidance, other than the fact that Australia wasn’t on the list of most dangerous destinations. So I reached out to some smarter-than-me friends, including a former ER doctor and a science journalist:

The doctor:

The only consideration I think you need to make is how well could you tolerate getting stuck outside the U.S. for 14 additional days...? Australia has excellent healthcare.

The science journalist:

I’d probably still go. Family can manage if you get quarantined there, and if any of you get sick it’s probably not serious. (None of that is great of course.)

I headed to Costco and built a pantry of emergency supplies in case things got really bad—enough pasta, flour, sugar, ground beef, frozen chicken, and frozen vegetables for two weeks. I grabbed a case each of toilet paper and paper towels.

The next day, I got on a plane to Australia and wiped down every surface I could reach from my seat, using homemade disinfectant wipes. The ready-made ones were sold out everywhere I had tried to buy them.

One of the first text messages I got Thursday morning when I landed was from my wife: news that three F1 team members had been quarantined and were being tested for COVID-19. One was from McLaren, and the other two were from... Haas, where I was slated to spend the day.

Events around the world were evolving at a whiplash pace. Italy announced that it was suspending all commercial activity. In the U.S., President Trump announced that he was banning travel from Europe into the United States (without mentioning that U.S. citizens were exempt from this prohibition). Rudy Gobert of the Utah Jazz tested positive for COVID-19, and the NBA immediately suspended its season.

Even as the world accelerated, F1 didn’t. There was a studied nonchalance in the paddock that day. I saw people greet one another with an elbow tap to avoid shaking hands, but I witnessed others give exaggerated hugs as if in defiance.

The F1 caravan includes more than 1000 people who work for the race teams, as well as hundreds more who work for F1 and the media outlets who cover it. This group travels the world for nine months a year, clocking more than 60,000 miles as they criss-cross the globe to races on six continents.

The logistics of shuttling all those people around doesn’t even compare to moving their gear. Haas had flown 34 tons of equipment to Australia; some of the larger teams brought more. On an empty sports field near the Albert Park Circuit, hundreds of air-freight containers, each marked with its owner’s logo, stood ready to be packed back up at the end of the race weekend.

Even more complicated than the air freight is the equipment that each team ships by boat. They use sea freight to handle less critical kit that the teams need for each event: office furniture, catering gear, tire racks. It’s actually cheaper to make multiple sets of this stuff and ship it by sea. Haas, for instance, has six different sets of equipment that hopscotch around the world in two 40-foot shipping containers.

What’s the payoff for this massive effort? A huge business. Formula 1 had an overall income of $2 billion in 2019, and the teams split a pot of over $1 billion based on their performance on the track. Top drivers earn more than $30 million a year, plus endorsements. There are contracts on top of contracts on top of contracts—F1 ownership with teams and local race organizers and governments and broadcasters. Teams with drivers and staff and sponsors. Promoters with governments and sport governing bodies.

This huge machine of commerce and infrastructure underpins everything in Formula 1, and once the machine got moving, it was proving impossible to course-correct. It was like a car with horrible understeer. Even if anyone was trying to turn the wheel—and it wasn’t clear that anyone was—the damn thing wouldn’t take the corner.

So we continued with the regular schedule of events, including the traditional Thursday afternoon driver’s press conference. One of the drivers speaking was Mercedes’ Lewis Hamilton, a six-time world champion and the biggest star in the sport. Sitting on a stylish couch side-by-side with three other drivers, Hamilton blasted the decision-making that had led to him being in that room, packed with people from around the world.

“I am really very, very surprised that we’re here,” Hamilton said. “It’s shocking that we’re all sitting in this room. So many fans are already here today and it seems like the rest of the world is reacting...with Trump shutting down the borders from Europe to the States, you’re seeing the NBA’s been suspended, yet Formula 1 continues to go on.”

Hamilton’s comments—which in hindsight were spot-on, and the first meaningful voice of reason in the entire sport—rattled me. I went from feeling okay to wondering what I could have possibly been thinking. On my way back to my Airbnb, I stopped at a pharmacy and bought a thermometer. After it beeped, it read 36.4. I had to Google “normal body temperature in Celsius” to confirm that I didn’t have a fever.

By Friday morning, it was no longer the 2020 Rolex Australian Grand Prix. It had become the 2020 COVID-19 Schrödinger’s Grand Prix, a race that may or may not be happening, with fans in the stands or with no spectators, with all teams or with a limited number participating. Or not.

Word came down that the McLaren team member had tested positive for COVID-19 and that several members of the team would have to be quarantined. McLaren withdrew from the race. The remaining tests had come back negative, including the Haas staffers.

That left the big question: what next?

The team principals had gathered with F1 leadership overnight to discuss. Of the ten teams in Formula 1, four of them voted to cancel the race: Ferrari, Alfa Romeo, Renault, and McLaren, which had already withdrawn.

Other teams thought the risk was manageable and that since they had come all the way to Australia, they should go ahead and race. Four teams voted to continue: Red Bull, AlphaTauri, Racing Point, and Mercedes. The final two teams—Haas and Williams—abstained from the vote. It was a tie, 4-4. One team suggested that practice continue as normal on Friday, and then they could evaluate the situation at the end of the day. Ross Brawn, the director of motorsport for F1’s owners, endorsed that plan.

But after the meeting broke up, Toto Wolff, the team principal for Mercedes, got a call from headquarters in Stuttgart, Germany. I don’t know exactly what was said on the call, but Wolff changed his vote. A majority of teams now favored cancelling the race. News agencies across the globe reported that the race was doomed.

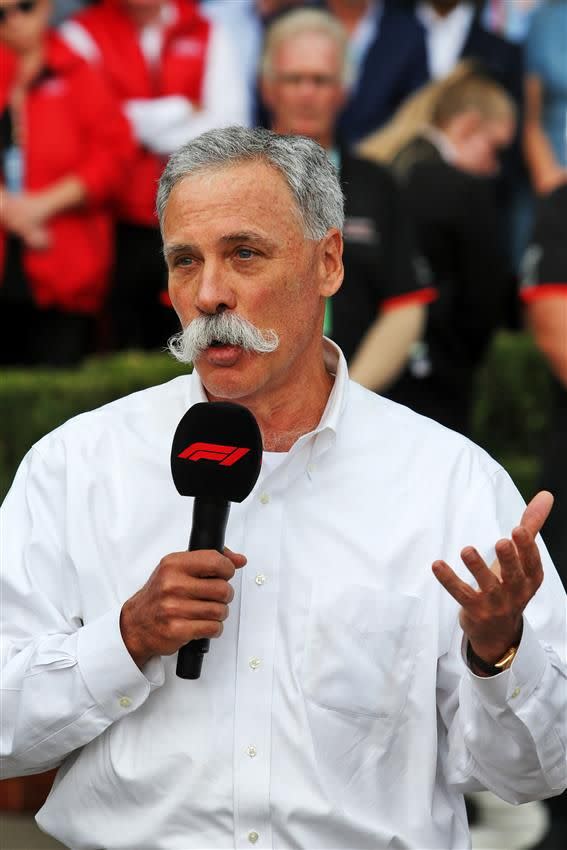

Yet there was no official announcement. Chase Carey, the CEO of F1, was on a plane, which certainly added to the confusion. But there were conflicting messages going out. Paul Little, the chairman of the Australian Grand Prix Corporation, went on TV and said that the track would open for fans as usual at 8:45 AM.

Those fans, clad in shirts and hats proclaiming their loyalty, massed in front of the main entrance to the Albert Park Circuit. There was Ferrari’s iconic red, the proud yellow of Renault, which employs Australian driver and local hero Daniel Ricciardo, and Red Bull’s logo-festooned blue polos with red side panels. On the other side of the gate, workers readied merchandise tents and food trucks, revving up another part of F1’s massive economic engine.

Every few minutes, hundreds more fans would press into the area, their faces a mixture of anticipation of a fun day at the track and uncertainty about what actually was going on. They gathered by the metal detectors, side-by-side, much too close to one another, and wondered when they’d be let in.

At 8:46, a marshal appeared and addressed the crowd by megaphone: “Gate opening is delayed while we work through today’s programming and scheduling.” Everyone grumbled and pulled out their phones to try and figure out what was going on. The hottest information we saw was a report that two F1 drivers, Kimi Räikkönen and Sebastian Vettel, had left Melbourne on a 6 AM flight to Dubai.

I left the gate and walked underneath the track to the paddock. It was just before 9 AM, and mechanics were also clustered by their entrance. Formula 1 rules include a curfew designed to give mechanics time away from the track; they were just about to be let back in, which would give them three hours to get their cars ready for the first practice session of the weekend.

The top of the hour came, and mechanics streamed through the gates. I watched them stride purposefully toward their garages: Williams, Haas, Alfa Romeo, Racing Point. McLaren’s mechanics obviously weren’t there. But neither were Mercedes’s. Or Ferrari’s. Renault’s crew was missing, as well. Four of the ten teams on the grid were absent.

“Who’s in charge?” I asked one team principal.

“Who the fuck knows?” he responded.

Meanwhile, many of the teams were packing up their gear. Mechanics pushed massive racks full of tires that wouldn’t touch tarmac in Australia. Forklifts sped back and forth on the narrow lane between the garage complex and the teams’ hospitality suites. Fifty-five-gallon drums of race fuel were carefully placed on pallets and taken away. Clouds started to blow in, replacing the early morning’s bright sunshine.

Then, an official announcement: the race was canceled. It was 10:11 AM.

There was a hastily organized press conference to explain the decision and why it wasn’t made or communicated sooner. Media stood corralled behind metal barriers, straining forward with our cameras and our audio recorders, trying to capture the explanations for the world. You can see me in some of the pictures from that morning (above). I now can’t imagine being in such close proximity with so many people.

“It is a pretty difficult situation to predict. Everybody uses the word ‘fluid’ and it is a fluid situation,” Carey said, having finally arrived. “The situation today is different than it was two days ago, and it was different than four days ago. Trying to look out and make those sorts of predictions, when it is changing this quick, it is challenging.”

After the race was finally called off, I caught up with Steiner. He was trying to balance his competitive nature with broader responsibility.

“We came to the other side of the world to race and we didn’t race,” he said. “I’m sure we will be very careful not to do this anymore. Hindsight is a beautiful thing.”

Is there anything anyone could have done to avoid this?

“The teams should have been louder before we came down here about our doubts,” he said. “I’m criticizing myself about it now. Sometimes when you’re too passionate about something, your views get steamed up.”

He looked tired; earlier he had told me that he just wanted to get home to North Carolina and take care of his family before there were any further travel restrictions.

“Normal is relative,” he said. “We’re used to this in Formula 1, this uncertainty. Things sometimes happen in F1 that for a normal person are irrational.”

I asked Steiner if I could go see the Haas garage—I hadn’t actually been in there yet. He chuckled and led me over.

Calling the area where a Formula 1 team works on their cars a “garage” brings the wrong picture to mind. It’s more like a clean room in a microprocessor plant. There’s not a speck of dirt or dust, not a drop of petroleum product on the floor. No tools or parts scattered around. Even in the midst of a global pandemic, I’d have eaten off the floor.

The two Haas cars were on stands, the team already tearing them apart. Mechanics were removing the powertrains to pack separately, and they’d Tetris the rest into the containers and send it all along to the next Grand Prix.

Except nobody knew where the hundreds of tons of gear should go. As of that moment, Steiner and I expected the Bahrain Grand Prix the following weekend to take place, with no fans in attendance. After that, F1 was slated to go to Vietnam. Then the whole caravan was supposed to head back to Europe and the heart of the season.

Within hours, organizers canceled Bahrain and Vietnam. Within days, races in the Netherlands and Spain were postponed. The fabled Monaco Grand Prix was cancelled. The Azerbaijan Grand Prix got postponed as well.

I said my goodbyes to Steiner and the Haas team, wondering if their “do-or-die season” would ever take place. I walked back to the Airbnb and did my own packing—I had changed my flight to head home Saturday morning. Once I was done, I decided to spend my last evening in Melbourne exploring the city.

The streets in the central business district were thronged. I saw people in suits leaving their jobs, tourists like me gazing at their phones to find their way around, babies in strollers. I came across a large band of F1 fans—maybe some of the same ones who were stuck outside the gate with me earlier in the day. It appeared that they had spent the intervening time in a pub.

I had come to Melbourne with a long list of bars and restaurants to try, recommendations from friends and colleagues, all carefully entered into Google Maps for easy access. I called up the map and found myself wandering back and forth through downtown Melbourne, seemingly unable to commit to a spot. A light rain started to fall.

I came to a restaurant called Chin Chin that several people had recommended. Large windows ran along the side of the building, showing a massive arched mirror behind a long bar, well-stocked with hundreds of spirits. It was crammed full of people, a huge line snaking out of the door. Normally, I would have stepped out of the drizzle and found a seat at the bar to have a quiet dinner and drink on my own, enjoying the people-watching, the novelty of a new city.

Instead, I felt a mounting fear. I started to move toward the host stand, and then backed away, and then did it again. I couldn’t make myself get into the line; the rewards didn’t seem worth the risks. I caught a tram back to my Airbnb, standing carefully facing away from the other passengers. I stopped at a grocery store to get something to eat and sat on the couch to watch a rugby match with my supermarket sushi.

When I finished the first draft of this story, the F1 season was set to begin in May. The series restarted in July. But the race schedule is still changing—quick.

As for me, I spent 50 hours and 48 minutes traveling 21,896 miles to and from Australia. I spent 52 hours and 11 minutes on the ground in Melbourne.

I’ve still never seen a running F1 car.

You Might Also Like