An Insider’s Look at the Bizarre Corporate Culture That Brought Us Amazon.com

As in so many relationships, Kristi Coulter’s breakup with Amazon, where she worked for 12 years, captured her entire history with the jilted megacorporation. She had expected to get the chance to pass on to someone in-house what she’d learned and experienced, she writes in her new memoir, Exit Interview: The Life and Death of My Ambitious Career. Hadn’t she worked in five different divisions at Amazon, and hired some 700 people? Wasn’t she a “woman in leadership” at a company that had been fiercely criticized for its brutal, predominantly male workplace culture and had vowed to fix its gender imbalance? She had plenty of feedback to offer, and isn’t it one of Amazon’s quasi-scriptural “Leadership Principles,” parroted reverently by employees at every level, that good leaders welcome “diverse perspectives and work to disconfirm their beliefs”?

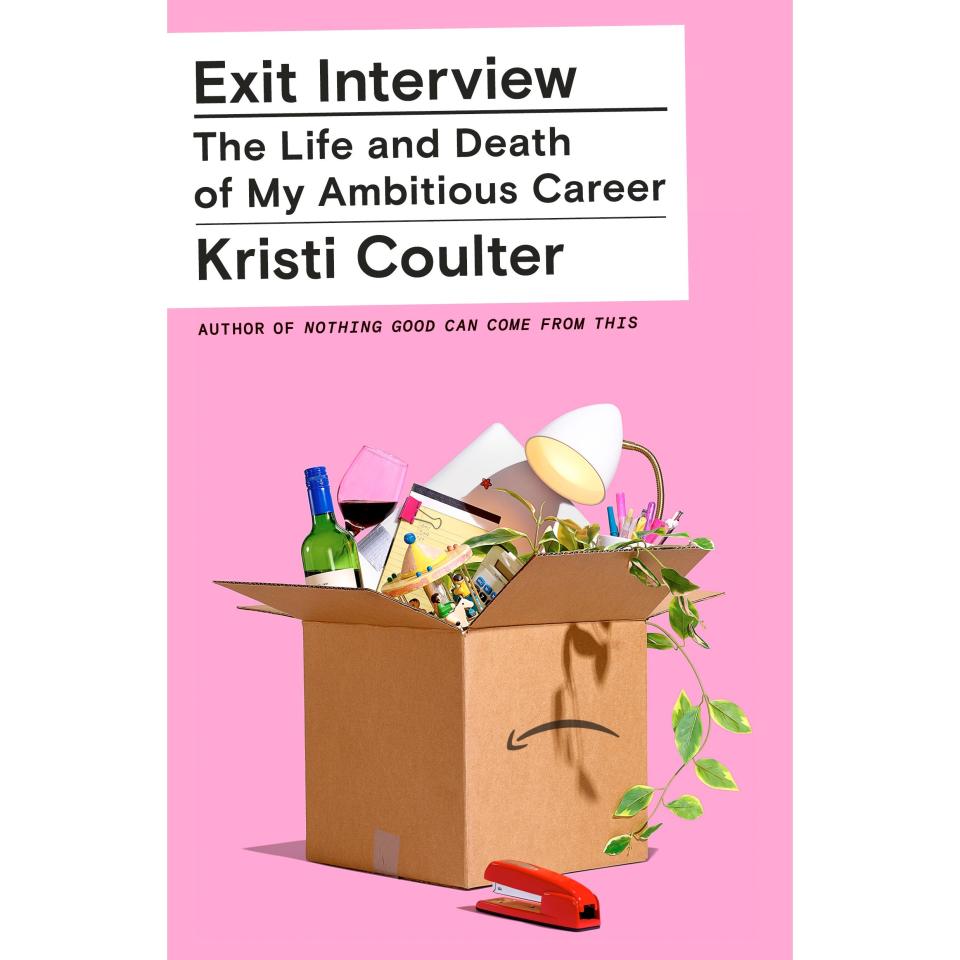

But instead of an in-person meeting when she left the company in 2018, Coulter got a link to fill out a form. She spent two hours distilling her decade-plus of dysfunctional and occasionally exhilarating work into several hundred words, then clicked Submit. The wait cursor spun and spun—which was typical. Throughout Coulter’s tenure at Amazon, she had struggled to get substandard internal software like this debugged. After a few other attempts, “the page hangs for another second and then it’s blank and everything I had to say to Amazon is gone.” The next time she tried, she was locked out of the network, an ex-Amazonian. She never got that exit interview, so she wrote this enlightening and often wincingly funny book instead.

Tempting as it is to view Exit Interview as an indictment of Amazon, its relevance is broader. Coulter’s memoir is a document of the rise-and-grind hustle culture of the 2010s: the early mornings, the green smoothies and Bulletproof coffee, the grandiose mission statements, the 80-hour weeks, the sacrificed relationships. WeWork, indeed. Skepticism about this fever dream had percolated before 2020, but the pandemic seems to have properly killed it off. A couple of years out of the crucible has been enough to remind workers of just how intolerably hot it was in there. Books like Exit Interview provide a chance to look back and ask ourselves, What did we just do to our lives?

Hustle culture has been viewed as a millennial phenomenon, but its effects spread wide; Coulter is a youngish Gen Xer, in her mid-30s when she left a comfortable but dull job at a Michigan company producing metadata for entertainment media to do something vaguely similar at Amazon. In Exit Interview, she portrays herself as both ambitious and insecure, a high achiever adept at talking her way into jobs she only partially understands and then learning on her feet. In each interview she aced during her life, she writes, she sat “across a desk from a man old enough to be my father and I enveloped us both in a force field of earnest competence, the kind I’d been practicing since kindergarten with my hand permanently raised in class.” Accustomed to—in fact, dependent on—seeking and pleasing authority figures, she was ripe fruit for a company like Amazon, and they snapped her up. She and her husband, who was starting up a tech business of his own, moved to Seattle.

Coulter worked a whiplash-inducing variety of jobs within the company, rapidly assimilating into its corporate culture and adopting as her dearest goal the attainment of a series of promotions into its executive ranks. She describes Amazon as “a level-obsessed environment,” where employees begin at Level 4 (L4) in a hierarchy that tops out at L13, the CEO position occupied by Jeff Bezos. If she’s noticed the creepy similarity between Amazon’s Ls and the levels assigned to members of the Church of Scientology, she doesn’t mention it. At least with Scientology, the key to advancement—forking over piles of cash—is pretty clear. Working your way up at Amazon amounts to something of an occult art. When Coulter asked one of her supervisors what it would take to bump her up to L8, he replied, “It’s easy. Just change the world.”

Given that Coulter was at that point running the books-in-translation imprint for Amazon Publishing, this seems a pretty tall order. It was far from the only instance of management applying the overblown rhetoric of Silicon Valley (the industry and the satirical HBO series about it) to enterprises only tangentially related to computing. Amazon—apart from its hugely lucrative web services division—is only partly a tech company. Mostly it just sells stuff, in unimaginable amounts, through the mail. Yet the company’s corporate culture insistently referred to its origins in the proverbial garage—you know, just like Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak inventing Apple! “It’s always Day 1 at Amazon” is one of Bezos’ favorite mottos. (The company even launched a literary journal called Day One.) You can interpret that according to the official line, as a vow to stay “relevant” and to woo customers as if they’ve never heard of you before. Or you can recognize it as nostalgia for the company’s startup days.

The ethos—the romance—of the startup remains a potent imaginative force in both Silicon Valley and beyond. Arguably, the startup dream is the driving mythos behind all hustle culture. This dream encompasses more than just the possibility of getting rich, even if that’s its main allure. Fabulously wealthy men like Bezos like to hark back to their startup days not just to point out how far they’ve come, but to reminisce about a time when the team was small and unified, the sense of possibility and purpose limitless. Working at a startup can be thrilling (I’ve done it), but that thrill isn’t scalable to a company with 1.5 million employees and tendrils that extend into (and in some cases virtually own) every sector of the retail industry, from cat litter to prescription drugs. You can’t be Steve & Woz and also Procter & Gamble.

Nevertheless, plenty of young white-collar workers, weaned on the hero-worship of entrepreneurs by business media, can be hoodwinked into believing otherwise. The glamorous aura of the entrepreneur can be repurposed to delude a middle manager marketing DVDs into feeling as valiant as a Knight of the Round Table: Doing the impossible! Driving innovation! Changing the world! At Amazon, Coulter worked under conditions of barely controlled chaos she likens to a “goat rodeo staged on a rusty Tilt-a-Whirl.” The office furniture was made out of old doors to comply with one of Amazon’s other core Leadership Principles: frugality. The same principle dictated that Coulter couldn’t replace a laptop until it was exactly three years old, even when said laptop “shut down randomly multiple times a day and took a full ten minutes to reboot each time.” (She dubs this inflexibility “frupidity.”)

Another advantage the entrepreneurial mystique offers a big employer like Amazon is perspective shrinkage. It makes sense that the heightened stakes of a startup will take over your life. But a job at a Fortune 500 company shouldn’t. Any all-consuming workplace will eventually blot out the world beyond it. Coulter got so caught up in the quest to be Amazonian—to thrive during constant and often pointless changes of plan, to stoically suck up disappointment or even outright abuse (one manager called her “stupid” to her face), to pivot on a dime to an entirely different and unfamiliar job—that she never had time to question the worth of any of it. Of course, there was the money, particularly a stock-vesting structure that incentivized sticking it out, but in time she came to believe that she couldn’t work anyplace else, that her skills and experience were too fractured to have any value outside Amazon. Coulter became so blinkered that when she read a shocking New York Times article about the working conditions in Amazon’s warehouses, her first thought was “Oh yeah, we have warehouses.” (Her second was, “I can believe all this happened.”)

Like many workplaces that cling to the fantasy that they are still a scrappy tech startup, Amazon internal culture insisted that it based every decision on “hard data.” “We need to be hiring people with degrees in the hard sciences,” one manager absurdly insists, during a meeting about hiring new merchandisers for the housewares department. “Physics, geology.” Anything to persuade themselves that they were in any business but sales—a field of human endeavor firmly rooted in irrationality and whim. Despite the company’s constant urges to “innovate,” the idea that its bro-ish leadership could benefit from perspectives unlike that of a white, male Stanford comp-sci graduate rarely seemed to occur to them.

The stress of working at Amazon literally drove Coulter to drink, and then to stop drinking when she realized that she couldn’t function in her demented workplace while hungover. She published a viral essay asserting that pretty much any woman would hit the sauce when faced with the sort of gaslighting she’d encountered in her career. (After she acknowledged during a panel presentation for summer interns that a woman needed a “thick skin” to work at Amazon, a male panelist disagreed, insisting that the company wasn’t tough on women at all.) This led to a contract for a book about women and alcohol, but even that encouragement and the success of her husband’s actual startup wasn’t enough to convince Coulter that she could survive outside the Amazon fathership. How would she afford stuff like the Prada wedges she’d bought herself as consolation for how miserable her job made her?

The spell finally broke when yet another male underling was promoted over her, despite the fact that he hadn’t changed the world, either. When she quit, another ex-Amazonian gave her the name of a trauma counselor, saying “He’s worked with a lot of us.” Readers of Exit Interview will have spent the whole book anticipating the moment when Coulter walks out that door and back into the real world, primed to learn what so many of us would be forced to figure out under lockdown two years later: When you live every day like a hustle, you’re really not living at all.