How international efforts in facing past wrongs help NBA fight racism

The city of Brunswick in Germany, Braunschweig as the locals call it, harkens to a medieval past as well as a modern future. It is a city that helped aid the rise of Adolf Hitler, and one that was nearly destroyed by the time World War II ended.

Today, Braunschweig is a modern, diverse city that attracts young people. It’s where Oklahoma City Thunder guard Dennis Schröder grew up.

His childhood there wasn’t perfect. As a Black kid growing up in the predominantly white nation, whose father grew up in Germany and mother emigrated from Gambia, he experienced racism. When he moved to the United States, he wasn’t surprised to see racism here. But it felt different.

“It was kind of like a culture shock,” Schröder said.

He wasn’t accustomed to the care that Black men had to take around police officers, or even walking down the street. The concept of gun violence was foreign to him, as was the idea that he was safe because he played in the NBA, but others with his skin color weren’t.

When he thinks about his future and that of his young children, Schröder would rather they grew up in Braunschweig.

“It’s just safe, I know everybody,” Schröder said. “I can say nothing is gonna happen to me there. I don’t have to worry about anything.”

In Schröder’s personal history, several concepts about American race relations meld together. Braunschweig, like other parts of Germany, has confronted its ugly past — Schröder started learning about it as a preteen.

Scholars, activists and politicians lately have considered the differences in the ways that Germany confronted its actions during the Holocaust with the way America confronted its past of slavery, the Jim Crow era and racist policies that followed. Many people see the difference as obvious: America doesn’t honestly talk enough about its past.

“You go to Germany and there’s markers everywhere where Holocaust victims were,” former Clippers coach Doc Rivers said. “They’ve come to grips with what they did. They’ve paid reparations in Germany. They still are. We’ve yet to come to grips.”

For the last several months the NBA has tried to be part of a move toward change. With the death of George Floyd, a Black man in Minneapolis who died after a white police officer kneeled on his neck for several minutes, came nationwide protests and reckonings. Before the season resumed in the bubble, the NBA considered how it could help steer the conversation.

In Germany, whenever you get pulled over [by police] you ain’t gotta be worried about anything.

Dennis Schröder, NBA player from Germany

In the bubble on the Disney World campus near Orlando, Fla., players and coaches speak about examples of racism, sometimes from their own experiences.

“The more talented and affluent and elite you are, the more tempting it is to simply do the comfortable and convenient,” said Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit organization committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States. “Which is why I am impressed by what the league has done and what the players and coaches have done.

“They know that some fans are not going to be happy, may never forgive them for speaking about these issues, and they’ve done it anyway.”

::

Stevenson often talks about the differences in how Germany and America reflect on their pasts. He sees South Africa’s post-apartheid actions, forming a truth and reconciliation commission, as a model. In Rwanda, tourists can visit a stark, unvarnished museum about the country’s 1994 genocide.

Once World War II ended in Germany, the country didn’t immediately look inward. Rather, in many ways it avoided the subject. Not until the late 20th century did Germany truly start to educate its citizens about the Holocaust, a process that intensified after the Berlin Wall fell in 1989.

By contrast, about 30 years after the American Civil War ended, Southern states began erecting monuments honoring Confederate leaders as a way to intimidate Black people.

German cities include memorials to Holocaust victims and survivors, to families who were abducted during the war. German children learn about their own towns’ histories, as Schröder did.

“There was a sense of responsibility,” said Washington Wizards center Moe Wagner, who was born in Berlin in 1997. “We learned a lot about it and heard about it. I hated history because we had it all the time. I wasn’t a fan, but you kind of develop a sense of responsibility for your country.”

No kid is born with hate or racism — it’s taught.

Daniel Theis, Celtics center from Germany

The country’s education on the Holocaust has its critics who feel that it doesn't go far enough. And despite its efforts, Germany has not been immune to the neofascism that has spread to some parts of Europe and America. But the movements are illegal in Germany, as is honoring Nazis in any way.

“No kid is born with hate or racism — it’s taught,” said Daniel Theis, a Boston Celtics center who grew up near Braunschweig. He remembers learning about the Holocaust in elementary school. “In Germany, in school you learn about the history early. You learn what happened and you can look forward so it’s something that’s never going to happen again.”

Dallas Mavericks forward Maxi Kleber, who was born in Wurzburg, Germany, in 1992, remembers visiting the memorial to the concentration camp in Dachau as a teenager.

When NBA players decided to wear social-justice messages on the back of their jersey, Kleber wore “gleichberechtigung” on the back of his — German for equality. The Mavericks chose in unison to wear “equality” on their jerseys with five languages represented — English, German, Spanish, Latvian and Slovenian.

::

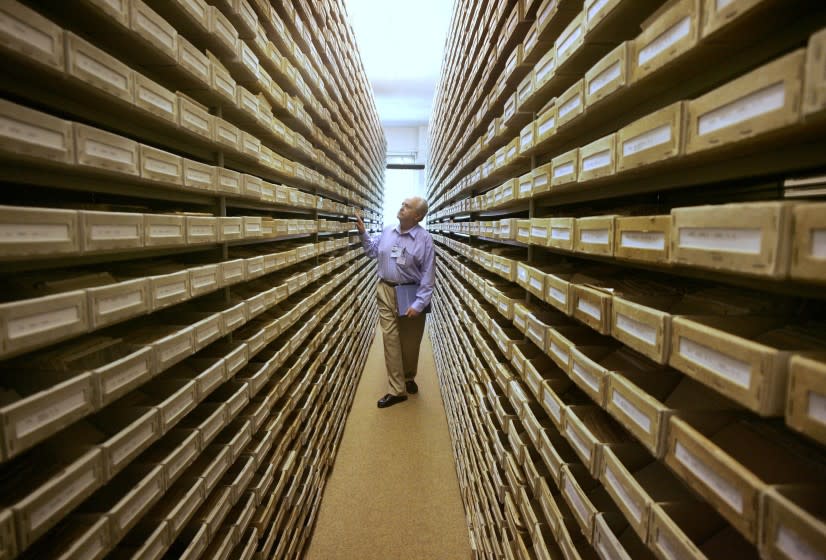

The NBA Coaches Assn. began a partnership with the Equal Justice Initiative this summer. When Stevenson began working with them, he stressed the importance of education. He provided them with calendars that list a different sordid anniversary of racial injustice in America every day of the year.

Dallas coach Rick Carlisle didn’t take questions before he started his pregame news conference before Game 1 of his team's first-round series against the Clippers.

“Aug. 17, 1965, riots in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, sparked by white police beating a young Black man leave 34 dead, 1,032 injured, nearly 4,000 arrested and nearly $40 million in damage,” he said.

San Antonio coach Gregg Popovich, in response to a question about whether or not forward Marco Belinelli would be active, discussed a North Carolina law that was passed 120 years ago designed to prevent Black people from voting.

“The great evil of American slavery wasn’t involuntary slavery and forced labor,” Stevenson said. “It was this terrible idea that Black people are less deserving, less human, less evolved, less worthy, less credible. And that manifests itself every day in the streets of America.”

More than 10 million people were brought from Africa to the Americas in the slave trade, with an additional 2 million dying during the passage. Although only a fraction of those 10 million came directly to North America, by the 1800s there were about 4 million American slaves.

“When the slaves were emancipated the ideology of white supremacy was never addressed,” Denver coach Michael Malone said. “‘OK, I can free you but that’s just on paper. That’s not in our ideology as a country. You are still lesser than us, you are still unequal to us as white people.’ … We as a country have never taken away the ideology of Black people are lesser than white people. How do we go about that? After 400 years how do we go about addressing that and changing that?”

Stevenson sees education as a critical element to addressing that mentality.

“We sang Dixie songs in high school, in grade school, and we almost celebrated slavery like it was a cool thing,” said Rivers, who grew up in Illinois. “You know, think about it, Black kids singing songs about picking cotton and how absurd that is. When I was a kid I didn’t think anything of it. Thought it was a cool song. And then we grow up, you’re like, ‘What the hell was that?’”

::

Kleber, who came to the U.S. in 2017, stressed that racism is a global problem. He has also learned a lot about the experience of Black people in America during the last few months through video and phone calls with teammates.

“For me it was very eye opening,” Kleber said.

Those conversations aren’t exclusive to the Mavericks, and they have changed the way some international players understand America.

"When I was looking in from outside without ever being in the U.S., watching all the stuff in media, TV, movies, everything, it seems like a perfect place," said Clippers center Ivica Zubac, who grew up in Bosnia and Herzegovina. "It took me to get here and get to know my teammates better to realize what they went through growing up."

It’s also changed how they look at their own societies.

“Germany has racism too,” Wagner said. “I have so many Black friends, they always get asked where are you from, or people start speaking English to them, that’s, like, racist. I never realized it but the last couple months made me realize it and be more aware for sure.”

Many Black Europeans quickly learn what it means to be Black in America when they arrive in the U.S.

“My culture obviously there’s a lot of people that might have felt racism … but I was never scared for my life,” said Milwaukee Bucks star Giannis Antetokounmpo, who was born and raised in Greece, the son of Nigerian immigrants. “[In America] people are scared to walk in the street because of the color of skin. You’re scared for your life. Things have to change. I just became a dad few months ago … I had the conversation with my girlfriend. It’s scary. It’s scary to raise a son here.”

Antetokounmpo recalled a lesson from his rookie year. Teammate Caron Butler told him to remove his hooded sweatshirt at night. Antetokounmpo didn’t understand why, but he does now. It was a safety measure lest someone assume he’s dangerous.

“Here you really gotta be careful what you say because you don’t know how the policemen or whoever you’re in that situation with, how he thinks,” Schröder said. “That’s perfect words what Giannis said. In Germany, whenever you get pulled over you ain’t gotta be worried about anything. Of course they’re going to check you or whatever, but that’s everywhere. Here when you get pulled over you gotta be really smart with your words [so] that nothing happens to you.”

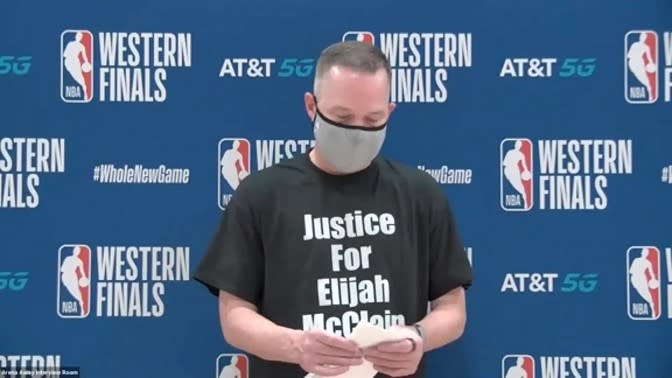

During Denver’s playoff run, Malone often wore a shirt that said “Justice for Elijah McClain,” referencing a mild-mannered 23-year-old who died after being aggressively restrained by police and injected with a sedative. Police were called because someone reported McClain looking “sketchy.”

“Being Black isn’t suspicious,” Malone said.

Said Stevenson: “I’m a middle-aged Black man. I’ve got a law degree from Harvard law school, got a bunch of other degrees … and I still go places where I’m presumed dangerous and guilty, where it is my burden to make sure that I assure a law enforcement officer or a store owner that I’m not a threat.

“… The fact that most people didn’t participate in a mob lynching, didn’t participate in enslavement, didn’t pass the laws that codified racial segregation, doesn’t mean that they don’t have an obligation to address all of the adverse consequences that flow from that history.”

::

Since they arrived in Orlando, the question has persisted — what can the NBA actually do to fight racism and injustice?

One answer was to use their interview sessions to force people to listen. Players would begin news conferences with discussions of racial injustice; some would refuse to discuss anything else. More than once players felt overwhelmed in postgame on-the-court interviews.

Denver guard Jamal Murray fell into a squat on the court, emotionally exhausted, before discussing racism. Lakers star LeBron James spoke passionately about fear of police in the Black community, and has shared his worry for his children. The Bucks staged a walk-out on Aug. 26 that the rest of the league joined, after their emotions boiled over following the release of a video showing police repeatedly shooting an unarmed Black man in the back in a town only 40 miles from their home arena.

The Bucks were led, in part, by Sterling Brown, who was physically attacked by police for parking illegally in an incident that was captured on video.

They’re just conversations, and they won’t change everything by themselves.

Even those conversations, Stevenson says, will begin to help.

“The league is doing an amazing job fighting for it,” Schröder said. “We just gotta keep pushing and maybe one day you can raise a family in the States and don’t have to be worried what happens to my daughter or my son.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.