Intuition in the age of analytics ∣ Vantage Point

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Chances are, you don’t know who Alexander Fleming was or who discovered penicillin. Now you know both.

Fleming’s discovery – one of the most civilization-changing events ever – is a story about more than bacteriology or medicine; it’s about intuition and where that can take us, if we would just let it, especially now, when decision-making is so sternly, tyrannically dictated by analytics and metrics.

Fleming (1881-1955) was a British bacteriologist with a keen intuitive sense, renowned for original observation. In other words, he saw things others did not. He recognized the unusual. He also was a technical mastermind, but that, history affirms, was second to his intuition.

More Vantage Point:Historic workplace change underway

Case in point. On Sept. 3, 1928, Fleming spotted something highly unusual in a petri dish in his lab. In a famous photo, there is on one side of the dish a large amorphous blob; on the other, a highly populated colony of bacteria; and in between, an area of almost nothing, kind of a demilitarized zone of sorts. What struck him – a purely visual observation at first – led to a question: What was it about that large mold that enabled it to prevent the advancement of that colony of bacteria? As it turns out, the mold, Penicillium notatum was inhibiting and repelling growth of a colony of Staphylococcus aureus.

Fleming had just discovered penicillin. Although it was technically not the first antibiotic, it instantly made the field and the product a phenomenon, and it took only three years. By 1931, penicillin was commercially viable globally. Life on this planet had changed thanks to the intuition of one man: Alexander Fleming.

Now, how did this story go from situation to curiosity to creativity to innovation? Simple. There was nobody to get in Fleming’s way. Nobody insisted that work could not be done without data-based permission. Nobody supplanted his hunch with doubt. Nobody told him we’ve never done that before. Granted, Fleming had a reputation for sharp insights and meticulous experimentation practices, so he wasn’t encumbered by skeptics, bureaucrats, micromanagers, regulations and preconceptions. But what if he were?

Over the last quarter century, aside from doing career coaching for which I’m most widely identified, I provided leadership advisory to corporate clients in 25 industries. The industry I served more than any other was pharmaceuticals and biotech, and when I’d get a leadership team together in one room, we’d study the Fleming story. Then I’d ask, “If Alexander Fleming worked for your company today, would he discover penicillin?” Or would there be someone, something, some preconceptions, some rules in the way? That was inevitably a pivotal moment.

Years earlier, when Thomas Edison was asked what rules he established at his labs, he shouted, “Rules? We’re trying to get something done.”

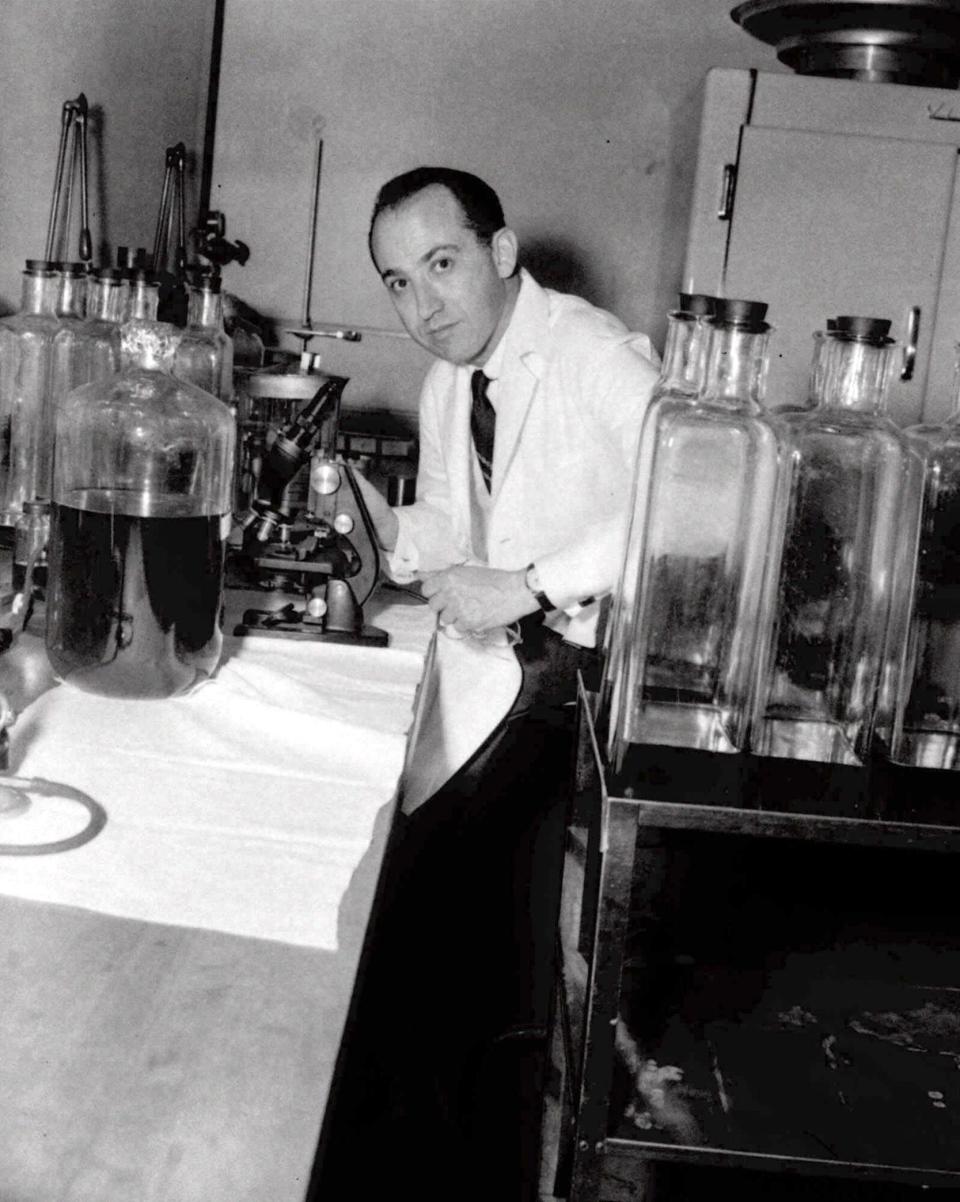

Germane to this story, I refer to another bacteriologist who changed the world: Dr. Jonas Salk (1914-1994), whose intuition led to his development of the polio vaccine, which was released en masse in 1955.

More Vantage Point:What does the historic job market mean for your prospects?

Sadly, just as few people recognize Salk’s name and accomplishment as they do Fleming’s. I know; in 15 years of teaching a leadership course in FDU’s MBA and MAS programs, a discussion of Salk always came up. Most students – from their 20s to 60s – didn’t previously know his name. When you think about it, though, 86% of people alive today never lived in a world with polio, either.

Salk, born and educated in New York, wound up leading the bacteriology lab at the University of Pittsburgh, where he made his breakthrough in the early 1950s. I promise to write on him soon, but as I’m starting to run out of room, I must bring up something Salk said that validates the Fleming story, explains Salk’s success, and should serve as a powerful lesson , for us, whether we’re looking for a job, planning a career, working within a team, or doing any individual pursuit.

Salk said, “Intuition tells the thinking mind where to look next.” In today’s world, where nobody seems brave enough to be intuitive – in business, politics, investments, or sports (Oh, how analytics has taken the beauty out of that magical game of baseball! I’m allowed to say that; I saw Jackie Robinson play). No doubt about it; our glaring deficiency is intuition. Analytics alone won’t inspire our next great advancement.

As Nobel Laureate Niels Bohr once retorted in a fiery debate, “No, no! You’re not thinking. You’re just being logical.”

I’m Eli Amdur and I approved this message.

Eli Amdur has been providing individualized career and executive coaching, as well as corporate leadership advice since 1997. For 15 years he taught graduate leadership courses at FDU. He has been a regular writer for this and other publications since 2003. You can reach him at eli.amdur@amdurcoaching.com or 201-357-5844.

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Alexander Fleming's discovery tells us a lot about modern-day business