Iowa 4-H accused of systemic racism; Trump admin shuts down civil rights initiatives, source says

An Iowa teen allegedly calling a hotel maid the N-word at a 4-H conference. A man not hired for about 10 jobs allegedly because he is black. A woman accused of discrimination against her blond-haired, blue-eyed colleague. A cardboard cutout inviting Iowa State Fairgoers to take photos with the phrase: “Every Calf Deserves a White Face.”

These are a few of the behind-the-scenes allegations of racism or ethnic insensitivity raised against Iowa 4-H — the largest youth organization in the state — in at least the past five years, a Des Moines Register investigation found.

The accusations come at a particularly sensitive time for 4-H as organizers try to grow membership by diversifying their ranks and weather a controversial directive from the Trump administration that rescinded guidance on how to best include transgender participants.

In Iowa, the turmoil culminated in a lawsuit brought this month by John-Paul Chaisson-Cárdenas, the first statewide Latino leader in 4-H's 115-year history.

Director fired: Iowa 4-H director fired after gay, transgender inclusion policy inflames conservative groups

Chaisson-Cárdenas alleges he was repeatedly harassed and eventually fired last year because of his advocacy for race equality and gender identity protections among group participants and employees. He further claims in the lawsuit that his supervisors — three of whom are named as defendants in the lawsuit — repeatedly failed to address “systemic discriminatory practices” and reprimanded him for “'overreacting' when he attempted to address racist behaviors."

“The most beautiful thing about 4-H is tradition; the most problematic part of 4-H is tradition,” Chaisson-Cárdenas said regarding his lawsuit against Iowa State University, where the extension office oversees the state 4-H organization. "Some of those ‘traditions’ is who belongs in our program and who doesn't.”

John Lawrence, vice president of ISU extension and Chaisson-Cárdenas’ former boss, would not comment on the lawsuit directly, but said he does not make decisions based on “race, ethnicity or other characteristics that would be considered discriminatory.”

Lawrence, along with Bob Dodds, assistant vice president for ISU extension's county services, and Chad Higgins, senior director for extension, are all individually named in the lawsuit. Lawrence spoke with the Register for all three defendants.

“It's a large organization,” Lawrence said when presented with the Register's findings. “We have a lot of great staff and volunteers doing wonderful things for all Iowans. But I would agree that there are some challenges that come up from time to time. You've found many of those, and we continue to work on those.”

Iowa 4-H: How Trump administration pressure to dump 4-H's LGBT policy led to Iowa leader's firing

Dozens of 4-H members and leaders told the Register of racial tensions within the organization, including a former leader at 4-H headquarters who claims the Trump administration essentially shut down civil rights discussions within the federally mandated group. Meanwhile, pressure mounted internally as the national organization publicly stressed diversity as vital to expanding its reach.

Locally, some accused Chaisson-Cárdenas of an overzealous bent for civil rights advocacy, which they say sometimes included false assumptions or accusations. The result was increased racial discord, they say.

“I don’t know what the specific grounds for his termination were, but I know when it happened I actually praised God,” said Stephanie Bowden, a parent from Mills County who contends the “N-word” incident at the 4-H conference was based on spurious information promulgated by Chaisson-Cárdenas.

Loading...

Iowa 4-H — which has seen participation fall 11 percent to 94,132 since 2012, records show — has adopted the national diversity campaign “4-H Grows: A Promise to America’s Kids,” Lawrence said.

The plan calls for the organization to reflect, "the population demographics, vulnerable populations, diverse needs and social conditions of the country," by 2025 and is critical to its goal to grow membership from around 6 million to 10 million, 4-H national leaders have said.

While Iowa 4-H has not approved more specific diversity and inclusion goals, welcoming kids of diverse backgrounds is needed to keep clubs afloat, some local club organizers said.

During a recent 4-H Club meeting at Storm Lake High School, where the sign outside the building scrolls through “Welcome” and “Bienvenidos” messages on a computerized loop, 15 kids of color giggle as they work through team-building activities. They make plans to meet up later for a community service project.

For three years, the group has grown by partnering with the school district and elevating students of color into leadership roles, positioning them to recruit more participants from diverse communities.

“It's a better connection when you have someone of your color or someone of color talking to you about it rather than like — it kind of sounds bad when I say it — but having a white person talk about this and say, like, ‘Oh, it's for every culture,’” said Katiana Jepsen, a 16-year-old junior.

“Especially since, like, we don’t have any animals to show,” junior Beauna Thammathai, 16, added with a laugh. “I mean, we don’t have any of that, so then that also just proves to them that they don't need that, either, and that they can be part of it.”

4-H is a 100-year-old organization caught between well-established generational roots and an evolving multicultural world, said Sonny Ramaswamy, former director of the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the government agency that houses 4-H. As it modernizes, some push and pull could be expected, he said.

Ramaswamy, who worked in the Trump administration for two years, said he didn’t feel pushback to civil rights initiatives from his superiors. But since leaving in 2018, he said he has concerns about the lack of progress in diversifying 4-H.

Simply put, he said, “4-H does not reflect who America is.”

“By the nature of, you know, the 4-H Club situation, just the word ‘club’ to me implies that it's like the old country clubs, you know,” Ramaswamy said. “It's only for white folks, and all of you black folks and colored folks and others, don't you dare come here.”

Allegations of a racial slur by Iowa 4-H participant

Register reporters first learned of allegations of racism and cultural insensitivity within 4-H while investigating the treatment of LGBTQ 4-H participants. The Register began interviewing participants and reviewing hundreds of pages of documents on the subject shortly after Chaisson-Cárdenas was fired in August 2018.

Among the most overt incidents of racism reviewed by the Register was the claim that an Iowa 4-H member had used the N-word during a June 2015 leadership conference at a hotel in Washington, D.C.

Some staff members and guests at the conference center accused a group of six teens from Mills County of listening to loud rap music containing racial slurs, according to 4-H documentation.

When a black housekeeper approached to clean one of the two rooms where the teens were staying, she reported that a boy opened the door, and another boy from inside said, “The n----- is here to clean the room.”

More: Trump agency pressure to dump LGBT policy led to 4-H leader's firing

The incident was chronicled by Maria McNeely, a national 4-H director at the conference, who interviewed the housekeeper and other guests on the boys’ floor to confirm the account, according to documents obtained by the Register.

Reports of the incident made their way up the national 4-H chain and eventually to Chaisson-Cárdenas, who requested that instead of sending the boys home — as was being considered — they “turn this into a learning opportunity,” according to emails.

The boys were removed from the conference and asked to do community service, watch a video about race relations and attend the African American history exhibit at the National Museum of American History, records show.

Bowden — the parent who worked for Mills County extension at the time — required the boys to apologize to the housekeeper and made sure they completed their assignments.

As head chaperone, a 4-H employee and mother to one of the six boys in the two rooms, Bowden said she was put in an awkward position.

Bowden was not present during the alleged encounter with the housekeeper but, in retrospect, said she doesn’t believe the boys used the slur and wishes she had understood the situation fully before making them apologize.

Mills County Extension Director Alan Ladd confirmed there were disagreements about what happened among accounts from the hotel staff, the boys and their parents.

“I wasn’t there, but we tried to listen to both sides of the story,” Ladd said.

Lawrence said he was “vaguely aware” of the incident — which he called “unacceptable” — but was not directly involved in any discussions at the time. Lawrence, who has held various positions at Iowa State and extension since 1991, was appointed director in March 2018.

Bowden said Chaisson-Cárdenas inflated the incident and threatened to fire her if she pushed back.

Chaisson-Cárdenas denied any bullying. He said he made “recommendations” but “had no authority over her as a county employee.”

Each of the reprimanded boys maintained 4-H membership until graduation, said Bowden, who continued to work for extension for 18 months after the Washington trip. She said she tried to file complaints about how the situation was handled, but her requests fell on deaf ears.

“Nobody questioned his intent,” she said of Chaisson-Cárdenas. “Unfortunately, 4-H protected someone who I think turned around and vilified the state.”

Outreach efforts fail, sources say

As Chaisson-Cárdenas continued to push inclusion in Iowa 4-H, he said leaders in diverse communities complained about their local chapters’ lack of minority outreach.

In 2016, Monica Paulina Vallejo started her own chapter of Juntos — a 4-H program directed toward Latino members — but said earlier efforts were ignored or thwarted by uninformed 4-H staff from the Linn County extension office. She believes they slighted her because of her race and culture.

Ann Torbet, a development specialist for Linn County extension, directed questions about Vallejo’s statements to Lawrence, who said he didn’t know enough about the interactions to comment.

“4-H is, I think, a very good program, but it’s only for people, for white people,” Vallejo said. “And (4-H) has wonderful programs, but they never include diversity, and when they include diversity, it is because they have to.”

Frank Dunn-Young, a former 4-H youth field specialist in Polk County, felt similarly snubbed when he was hired to work on diversity issues in fall 2015.

He was assigned to assist “an advisory council” of Latino youth that would make recommendations to the 4-H State Council about how to diversify Iowa 4-H membership. Instead, the idea itself of the advisory council led to some “ugly conversations” among State Council youth participants about “why there had to be this other delegation,” Dunn-Young said.

Looking back, Dunn-Young said he doesn’t know if it was the youth of color that made the delegation “feel threatened,” or if suggesting that 4-H’s framework be more inclusive set some people off.

“Based upon what I saw, I would not feel comfortable sending my own child to be part of that circle,” Dunn-Young said. “As skilled as those kids were at speaking up for what they wanted, there was not the voice of understanding.”

Dunn-Young had hoped to be part of getting a new generation of kids involved in Iowa 4-H, but he felt like he was “constantly trying to crack the ice just to get started.” After about six months at 4-H, Dunn-Young left to work for the city of Des Moines.

“It felt very, very much like I was fulfilling some sort of a quota for them and that, really, part of me being there helped somebody sleep at night,” he said.

Lawrence, who was not familiar with the Latino advisory council, said he didn’t know enough about the situation to comment on Dunn-Young’s statements.

Tiffany Berkenes was hired by Chaisson-Cárdenas in July 2016 to fill Dunn-Young’s position. She said that she understood her predecessor’s concerns, but that he was employed when the group was just starting to focus on diversity.

Despite some challenges, Polk County’s extension has continued to nurture cultural inclusivity, Berkenes said, pointing to a Juntos 4-H group at North High School and regular outreach activities for LGBTQ 4-H participants and volunteers.

“We’re talking about change, and sometimes people have a tough time and there are growing pains, but we don’t let that stop us,” Berkenes said.

'Every Calf Deserves a White Face'

The lack of follow-through with minority outreach and failure to take racial concerns seriously was systemic, Chaisson-Cárdenas said, and resulted in cursory responses even when Iowa 4-H members were not the instigators of problems.

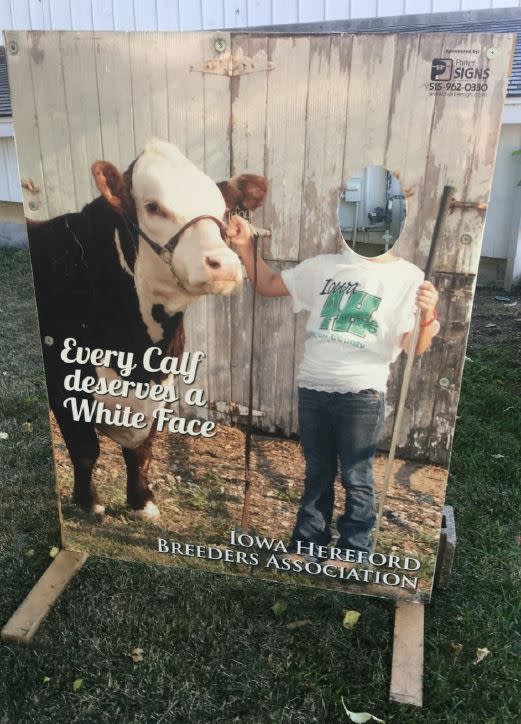

At the 2017 Iowa State Fair, Chaisson-Cárdenas came across the cardboard cutout outside the show arena featuring the phrase, “Every Calf Deserves a White Face.”

Sponsored by the Iowa Hereford Breeders Association, the placard showed a Hereford cow standing next to a white girl wearing a 4-H shirt with a cutout where her face should be. Fair attendees were invited to get behind the cardboard, standing in as the girl holding the cow, and have a picture taken.

The association meant the placard and the “white face” slogan to play off the distinct white pattern on the breed’s face.

Chaisson-Cárdenas said he asked the association to think about “consequences” of this message and requested they remove the placard, which they did.

Afterward, Chaisson-Cárdenas claims in his lawsuit that Lawrence told him “he had overreacted,” and, “he should have just ‘let it go.’”

Lawrence remembers the encounter differently. He said he not only supported Chaisson-Cárdenas’ decision at the time, but spoke with the Hereford association’s executive director twice, “to explain why that wasn’t appropriate at the State Fair.”

Lawrence pointed to the 4-H emblem on the girl’s shirt as a violation of copyright, just as Chaisson-Cárdenas had, but said he also talked about what the meaning the placard's words could have to people of color.

“This was right after the riots in Charlottesville in which a person was killed around race,” Lawrence said, “And I did not want that placard in a place like Polk County, with literally a million people going through that fairgrounds.”

Mike and Becky Simpson, longtime executives of the association, acknowledged they didn’t have permission to use the 4-H emblem, which was the reason they removed the placard. But they continue to question Chaisson-Cárdenas’ reaction.

“4-H has been an integral part of our life, and this left a bad taste in our mouth,” Becky Simpson said, noting her 2011 induction in the organization’s hall of fame. “It was just a bit over the top. It was someone looking for something to be offended by.”

The Hereford association still uses the “white face” slogan in promotional materials.

Volunteers, employees allege discrimination

Several ISU extension employees and Iowa 4-H adult volunteers say they have experienced racism and cultural insensitivity in their 4-H work, documents reveal.

“I feel like I am being treated differently because of the color of my skin, my accent and my culture,” Norma Dorado-Robles, an Iowa 4-H employee in Marshall County, wrote in a March 2018 email to Chaisson-Cárdenas.

In that same email, she noted that her colleagues made “fun of our 4-H State leader’s accent,” and that a co-worker claimed Dorado-Robles was discriminating against her “for being blonde with blue eyes.”

Dorado-Robles declined to speak to the Register about the situation, but noted she was recently promoted to a new role tasked with increasing minority participation in Iowa 4-H. If her outreach is successful, 4-H leaders may replicate the role in other parts of the state, Lawrence said.

Stan Hughes, a former Iowa 4-H county director in Fairfield, said he experienced a “very, very, very hostile, uncomfortable work environment,” when he worked with Jefferson County extension in 2016 and 2017.

“They would make comments like, ‘He doesn't know anything about this,’” Hughes said, noting what he heard from local board members. "‘He's not from Fairfield.’ ‘He's African American.’ ‘He doesn't know anything about farming.’”

After an extended absence related to an injury, Hughes said he received a letter in the mail that his position was terminated. Ashtin Walker, a coordinator at the Jefferson County extension, did not return a request for comment about Hughes' statements.

Chaisson-Cárdenas said he had a goal of diversifying Iowa 4-H's workforce when he started as the state director. But as he brought concerns about the treatment of minority candidates to his supervisors and extension’s human resources department, he was told that, as a minority, “he is biased towards minorities,” and “should completely stay out of the hiring process,” he wrote in a 2017 email to his boss, Chad Higgins, senior director of extension.

“In my role of State Leader of the 4-H program I have seen qualified minority applicants passed over time-after-time because of non-relevant criteria such as ‘not knowing us,’ ‘feelings’ and ‘fit,’” Chaisson-Cárdenas wrote in that email, which also outlined examples of what he called “a pattern of exclusion of racial ethnic minorities.”

The hiring issue was heightened for Chaisson-Cárdenas after Zadok Nampala, then an Iowa 4-H Foundation Board member, was passed over for about 10 jobs within 4-H, he said.

Nampala, who has a master’s degree in social work from the University of Iowa, said he was interviewed for several positions but overlooked for mostly white applicants he believed to be less qualified.

Nampala inquired about why he wasn’t hired, but nobody gave “a straight answer,” he said. He “absolutely” believes his race played a role.

“I had all the experiences, but I think they looked at me as a threat to their base,” he said, “and every time they brought back that, 'I just didn’t fit their culture.’”

“I am not the kind of person who is bringing up the race card, but when it’s there, it’s there,” Nampala said.

Today, 49 of the 55 people with 4-H youth development appointments are white, according to ISU data. Extension leadership is made up of 10 white people and one African American man, who is the group’s diversity officer.

Lawrence declined to comment specifically in response to these allegations, saying that he could not talk about personnel issues or didn't have knowledge of the particulars.

Lawrence said the leadership team was aware of Chaisson-Cárdenas’ concerns about hiring, but noted that ISU is “an equal opportunity employer,” and pointed to an HR process applicants could follow if they wanted to raise concerns about their interview experience.

Gains made, more needed, those involved say

While Iowa 4-H has made some gains in diversifying membership, far more work is needed, people involved with the group said.

Iowa 4-H enrollment in traditional clubs — where members can receive benefits like scholarships and field trips — has changed from 98 percent to 95 percent white since 2010, the group’s data shows.

Iowa’s population during that time has changed from 91.3 percent white to around 90.6 percent white, according to U.S. Census data. Iowa’s white population is expected to decrease further, to around 76 percent, by 2050, according to projections from the State Data Center.

Diversity and inclusion are “a priority” in Iowa 4-H’s strategic plan, Lawrence said, pointing to Dorado-Robles’ position as well as another recently created to work with the refugee community in Polk County.

“These examples you found are the outliers,” Lawrence said. “I think the culture of 4-H is a very caring and inclusive organization. It’s one that is trying to change and is changing with our changing demographics.”

Lawrence said he doesn’t see the classic rural program being in opposition to urban outreach, cautioning that nothing about their diversity efforts should be seen as diminishing “what has worked for nearly a hundred years.”

But the criteria of delivering 4-H programming — including when and where meetings and events are held and rules around club membership — are examples where, “we are going to have to flex to grow this program,” he said.

Minority recruitment — even in school districts like Storm Lake, where more than 80 percent of students are non-white — has been a challenge, said Ben Pullen, a youth program specialist for 4-H in Clay, Dickinson and Buena Vista counties.

Culturally Based Youth Leadership Accelerators, launched in 2015 with Chaisson-Cárdenas’ assistance, were designed to introduce minority populations to 4-H. Essentially statewide retreats, the accelerators feature culturally relevant activities for children whose families generally haven’t had previous interaction with the group.

Members of Storm Lake’s 4-H Club, which grew out of one of the accelerators, don’t describe the organization as having anything to do with farming or agriculture. To them, it’s about leadership, science, community service, self-expression and meeting similarly motivated kids.

Cleaning up the cups and strings from the meeting’s leadership activities, Thammathai said her personal goal for 4-H is to get one of her fellow Storm Lake students to join State Council, a special group of student leaders from across Iowa.

She is the only student of color on the council now, and, after looking at photos of past State Councils, recently realized she is one of the only ethnically diverse students to ever be a council member.

“It feels awkward for me because I am the only person of color,” Thammathai said, “but that still doesn't stop me, because it shows that someone like me can still do something that seems impossible.”

Follow Courtney Crowder and Jason Clayworth on Twitter: @courtneycare and @JasonClayworth

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Iowa 4-H accused of systemic racism; Trump admin shuts down civil rights initiatives, source says