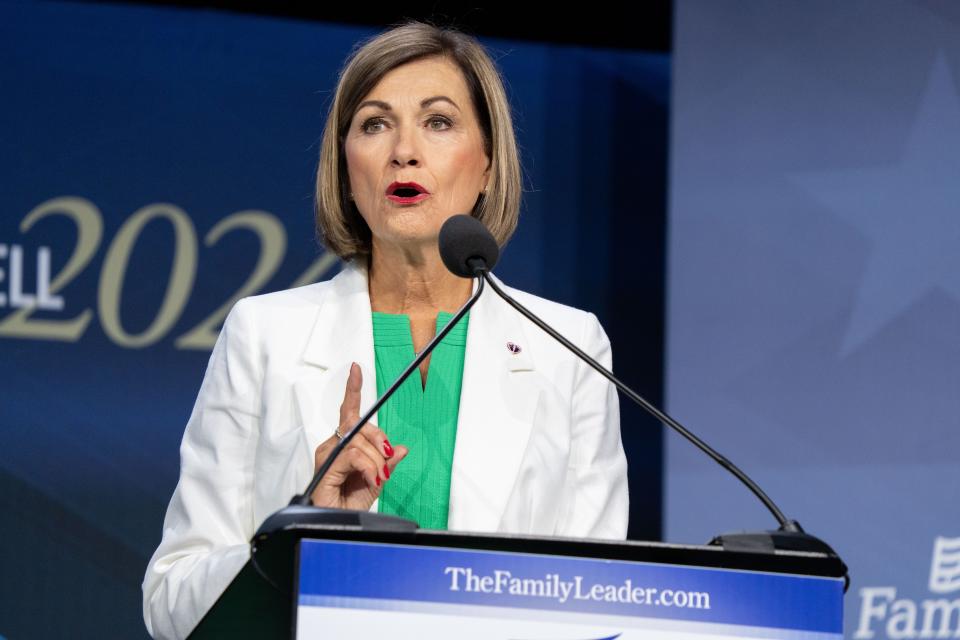

Iowa agribusiness magnate's access to Gov. Kim Reynolds paves way for pipeline, lawyer says

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

An attorney for Iowa landowners fighting a controversial $5.5 billion carbon capture pipeline has filed hundreds of pages of public documents detailing lunches and dinners between Gov. Kim Reynolds and Bruce Rastetter, the agribusiness magnate behind the pipeline.

Brian Jorde, managing attorney at Domina Law Group in Omaha, says the records showing Bruce Rastetter's efforts to arrange meetings with Reynolds demonstrate the Republican donor is using his political influence to stack the deck in the project developer's favor.

“Let’s not pretend that this has been a fair and transparent process for the people,” Jorde said. “It hasn’t been and it’s not going to be."

Kollin Crompton, Reynolds' spokesman, said the governor regularly meets with leaders in agriculture, insurance, technology and other industries "to help inform policy priorities."

"Concerns of ‘undue influence’ are completely unfounded and untrue," Crompton said in an email to the Des Moines Register.

Summit Carbon Solutions, a spinoff of Rastetter’s Summit Agricultural Group, seeks to build a 700-mile pipeline in Iowa that would be used to capture carbon dioxide emissions from ethanol plants, liquefy it under pressure, and transport it to North Dakota, where it would be sequestered deep underground.

If successful in winning a permit to build the hazardous liquid pipeline, Ames-based Summit Carbon Solutions would have access to eminent domain powers, with the ability to force unwilling landowners to sell access to their property for the project.

The issue is highly controversial. Nearly 80% of Iowans oppose the use of eminent domain for carbon capture pipelines, a Des Moines Register/Mediacom Iowa Poll in March showed.

Reynolds appointed the three-member Iowa Utilities Board, which on Aug. 22 launched a potentially weekslong hearing in Fort Dodge to consider Summit Carbon Solutions’ permit request for the pipeline. The board appointments required Iowa Senate confirmation.

“There's a clear directive that's been laid down from the governor. And I think we all know what that is,” said Jorde, who filed 888 pages of documents in the pipeline case detailing efforts between the offices of Rastetter and Reynolds to set times for lunches, dinners and other activities.

“This is a completely inside deal,” Jorde said.

Sabrina Zenor, a Summit Carbon Solutions spokesperson, declined to comment.

Pipeline opponents say they don't get the same access that emails show Bruce Rastetter got to Gov. Kim Reynolds

Reynolds and former Gov. Terry Branstad, with whom she served as lieutenant governor for six years, have received $423,200 in contributions from Rastetter over 13 years, according to OpenSecrets.org, a nonprofit research group that tracks money in U.S. elections.

Branstad, now president of the World Food Prize Foundation, also is a senior adviser to Summit Carbon Solutions.

The documents show Rastetter, whom Branstad appointed to the Iowa Board of Regents in 2011, invited Reynolds to speak at his annual summer party, attend political and university fundraisers, and join him in a suite at Iowa State University's Jack Trice Stadium to watch a football game.

Rastetter also had access to a top Reynolds administration executive, quickly receiving a call when he asked the governor's chief of staff to reach out to him in 2020, according to the emails, many of which were duplicate strings of email conversations.

Over the past two years, pipeline opponents — a diverse mix of conservative Iowa farmers, landowners and county officials along with climate and environmental activists — have repeatedly requested meetings with Reynolds to discuss their concerns, but they said they have failed to win an audience.

Jorde said Rastetter has been "schmoozing up politicians" on his "path to making billions" from the pipeline.

Summit has the potential to receive about $18.4 billion in federal tax credits over 12 years for the pipeline. The company anticipates the 2,000-mile pipeline will make it possible to capture and store 18 million tons of carbon dioxide annually from 34 ethanol plants in Iowa, North Dakota, Nebraska, Minnesota and South Dakota.

The company and its supporters contend that lowering ethanol's carbon footprint will keep the alternative fuel ― which uses half of Iowa's nation-leading annual corn crop ― viable as the nation moves toward a carbon-neutral future.

Iowa also leads states in ethanol production.

Iowa Utility Board changes preceded pipeline hearing

Rastetter, who started with 300 acres in the 1990s, has grown his business into Summit Agricultural Group, a massive hog, cattle, corn, soybean and farmland investment business with interests in Iowa and other Midwestern states.

Summit Ag also grows crops in Brazil as well as partnering with other firms to produce 560 million gallons of ethanol annually.

Rastetter is often referred to as a Republican kingmaker because of his large donations, fundraising efforts and political activism. Since 2009, he’s donated $2.5 million to local, state and national campaigns and political action groups, mostly Republican.

He gave $248,298 to Branstad’s gubernatorial bids in 2010 and 2014, according to OpenSecrets.org. And he has contributed $174,902 to Reynolds, who has won two gubernatorial elections since taking over the state's top elected spot in 2017, when Branstad resigned to become the U.S. ambassador to China.

In May, Reynolds named two new Iowa Utilities Board members: Erik Helland, a former Republican state lawmaker and Public Employment Relations Board member, and Sarah Martz, a mechanical engineer who worked for Alliant Energy for 11 years.

They replaced Richard Lozier Jr., whose term ended May 1, and Geri Huser, whose board term wasn't scheduled to end for four years, although her board leadership ended this year.

Joshua Byrnes, a former state lawmaker and Osage Municipal Utilities general manager, is the third board member. Appointed by Reynolds, Byrnes' term expires in 2025.

Crompton said Huser "announced her resignation at the expiration of her term as chair" after eight years of service.

"Gov. Reynolds greatly appreciated her leadership," he said. "Across state government, the governor has a longstanding policy of rotating board leadership and refreshing board membership to allow for new voices to be heard.”

Huser as board chair in 2016 voted to give a permit to the Dakota Access crude oil pipeline in Iowa, but she cast the losing vote against authorizing its construction in the state before all the other necessary permits had been obtained.

She did not respond to a request for comment on her departure from the board.

More: Iowa ag heavyweight Bruce Rastetter sets sights on $4.5 billion carbon capture pipeline

Jorde questioned why Reynolds replaced Lozier and Huser.

“What was wrong with them? The answer is nothing,” he said. “They at least had an open mind about this” case.

Pipeline opponents have complained about the new board's decision to move the hearing’s start to Aug. 22, saying the three-member panel is fast-tracking the hearing to meet Summit’s desire to have the permit decided by year’s end. The accelerated schedule, which enables Summit to present its case last instead of first, has failed to give opponents a fair hearing, critics say.

The old board had planned to start the hearing in October, which also was unpopular because it conflicted with the state's corn and soybean harvest.

The August start was set in an effort to avoid the peak harvest, Helland has said.

Several connections between Gov. Kim Reynolds, Bruce Rastetter associates

The emails show Rastetter expected to have a meal with Reynolds quarterly, although the dialogue was interrupted in 2020 as the state and nation struggled with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Legislative sessions, bill signings and Rastetter's and Reynolds' busy schedules resulted in them doing only a handful of meals over the four years, according to the emails, obtained by Jorde through Iowa’s open records law.

Jorde said the dinner and lunch meetings likely are just snippets of the communication between the governor and Rastetter.

Iowans have raised concerns about conflicts of interest since Summit began holding public meetings on the project two years ago, as required by state law. Some critics said Branstad's utilities board appointees — Lozier and Huser, whom Reynolds reappointed in 2021 — should recuse themselves from the case, since the former governor worked for Summit.

Critics also have pointed to Reynolds' and Branstad's ties to Jake Ketzner, Summit Carbon's vice president of government affairs. Ketzner served in Branstad-Reynolds campaigns and their administration from 2009 to 2017. Ketzner was Reynolds' chief of staff for about a year, beginning in May 2017. He joined Summit in June 2021.

In addition to Ketzner, Rastetter has hired attorney Jess Vilsack, the son of Tom Vilsack, the U.S. agriculture secretary and a former Democratic Iowa governor.

Branstad is still listed online as a Summit adviser, though he now leads the World Food Prize Foundation.

In April, a six-member Senate Ethics Committee tabled a complaint against state Sen. Mike Bousselot, an Ankeny Republican who worked as Branstad's chief of staff from 2015 to 2017 and then for Summit Agricultural Group as a managing director for eight months, beginning in 2017.

A member of Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement said Bousselot failed to schedule a commerce subcommittee meeting on a bill designed to limit the use of eminent domain, effectively killing it, because he had "deep personal, professional and economic ties" to Summit.

Bousselot called the complaint against him baseless, politically motivated and frivolous.

"Six years ago, I worked for Summit Agricultural Group (not Summit Carbon Solutions, which is a separate company and did not exist at that time). More than six years ago, I worked for Gov. Terry Branstad," he wrote in a response to the Senate Ethics Committee. "None of these facts serve as a basis for an ethics complaint under any Iowa law or rule within consideration of the committee."

There is a three-year statute of limitations during which the committee could take up the complaint again if someone brings forth further evidence of a conflict.

Des Moines Register staff writer Stephen Gruber-Miller contributed to this article.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Meals between ag magnate, Iowa governor aid pipeline, lawyer says