This Iowan almost died in Auschwitz. More than 80 years later, he’s telling his story.

Editor's note: David Wolnerman died Monday, Sept. 4, 2023. The Des Moines Register interviewed him last year before a tribute concert. Here's his story:

Children and the elderly were being sent to the left. Same for those who looked sickly or disabled.

The healthy — strong and vital — were pointed right.

Waiting his turn, David Wolnerman watched the German soldier give the queue a once over, maybe ask a quick question, before his stick and his full-throated shout indicated which way each prisoner should go.

Wolnerman was 13, in the no-man land’s between youth and adult; that moment where he was not the boy he’d been and not yet the man he would become. But recent fear and loss had demanded he grow up quickly, and what was ahead would only hasten the journey.

Just six months before Germany brought war to his small town in Poland, his father died unexpectedly, leaving his mother to support four children. And a few months after hate became law in Modrzejo, after prominent Jewish business owners were flogged in the town square and the local synagogue burned, soldiers forced their way into Wolnerman’s house with an ultimatum.

More: Family of boy who died at Adventureland seeks $98 million from the state of Iowa

Report to a work camp up the road, they said, or we’ll kill your mother.

That was no choice at all, Wolnerman says. So to the camp — a place called Auschwitz — he went.

How old are you? The soldier asked when Wolnerman reached the front of the line.

18, he replied without thinking, a deception he considers divine intervention. I am 18.

Right, the soldier yelled.

Wolnerman later learned those directed left were killed immediately. He and the rest pointed right were sentenced to hard labor for being Jewish or Polish or some other group their jailers considered less than human.

Death would come to them, too, if the guards had their way. But they’d be slaves first, the life starved and tortured out of them slowly. For five years, Wolnerman moved between locations so notorious their names alone have become the embodiment of evil: Auschwitz, Birkenau, Dachau.

“If I would tell him I’m 13, I wouldn’t be here. I would go left,” Wolnerman says, his meaning clear but his English broken. “Had to be God. I was too small to be smart.”

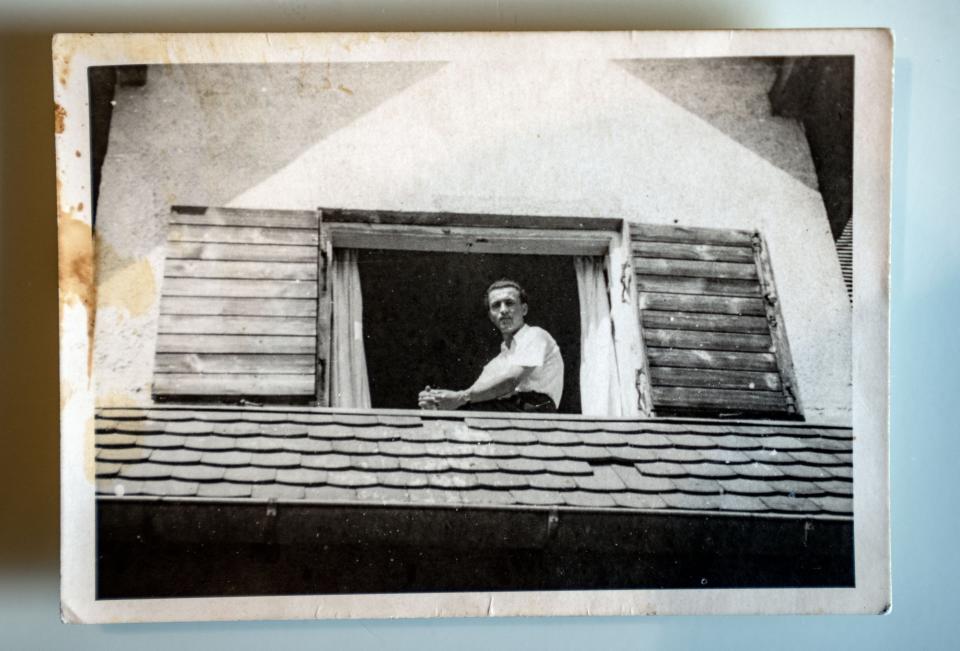

More than eight decades removed from the lie that saved his life, Wolnerman is Des Moines’ last known Holocaust survivor and one of the few left in Iowa. In his 95 turns around the sun, he's weathered ups and downs across two centuries and balanced more than his fair share on the razor's edge between life and death.

More: Acknowledging 'strong feelings on both sides,' Iowa corn association backs carbon capture pipelines

Prayer and his deep belief that celestial forces are listening, are gently guiding his way, were the keys to his survival; the shelter he took when the storm of life came in so strong he wasn’t sure he’d make it through the torrent. That he’s on this side of that final veil telling his story of perseverance — one which will be honored at a special quartet concert and film presentation on Wednesday — is still due to prayer, he says.

God was there then, as He is now, as He will forever be, Wolnerman says. He prays. He survives.

Wolnerman wasn’t always comfortable with his role as survivor, joking with those who asked about it that the blurry tattoo on his arm was just an old girlfriend’s phone number. But there’s an urgency now, an urgency both he and his loved ones understand even as they eschew its morbidity.

The people who experienced one of history’s darkest chapters — whether as prisoners or soldiers on the front lines — were dying exponentially before the COVID-19 pandemic ravaged the elderly. With the youngest victims now in their late 70s, the losses will only accelerate.

And with social media offering Holocaust denial a loudspeaker, flattening the distance between fact and conspiracy, the time to establish inalienable truths is now.

So Wolnerman takes a breath, and he tells his story.

‘Nobody thought we could be free again’

Wolnerman’s family was poor, but so were many families in tiny Modrzejo.

The town had one policeman, one doctor and one radio, always kept in a windowsill facing outward, so everyone could hear, Wolnerman says. The community subscribed to a kind of rural collectivism that crossed normally bright religious and ethnic lines. You offered food to a hungry neighbor so when your stomach was empty someone would return the favor.

More: Tour the renovated Polk County Historic Courthouse in Des Moines

When the Germans came to town, that collectivism was ripped apart by force, and tribalism became the order of the day. Wolnerman's older siblings lost their jobs at a local printing press, instead doing hard labor for pennies — or having no work at all.

A gentile friend of David’s started sneaking him a loaf of bread every day, risking death for his entire family if he was found to be helping a Jew. The Wolnermans would eat half and the rest David sold, scraping together not nearly enough to live.

He prayed. He survived.

Then the soldiers came to his house with the ultimatum.

At Auschwitz, he and another boy were forced to work in the crematoriums. They’d stand on either side of the oven’s opening and push bodies in, Wolnerman says. Babies, he adds.

“The boy I worked with, his mother and his father, he had to push,” he says. “I never talked about this. Terrible, terrible. The worst thing in my life.”

New prisoners were swarmed for information, sometimes about the war, mostly about a brother or a mother or a town. “Everybody was looking for somebody,” Wolnerman says.

But behind the bars and the gates that demarcated his entire world, Wolnerman's mind couldn't focus on much but food.

“We didn’t talk nothing, just 'piece of bread,'” he says. “That’s the whole talking, bread. Because nobody thought we could be free again. Nobody.”

Wolnerman ran with a group of about 10 boys his age and an older boy who watched over them. The older boy taught the kids the ways of the camp; how to huddle for warmth, how to save at least part of their nightly bread ration for the morning so they’d have something in their stomachs as they worked.

For the starving, saving seems fruitless, but Wolnerman tried. He prayed. He survived.

Once, as they tried to pass the endless hours, the older boy asked the kids a hypothetical question: You could keep getting one piece of bread a day and live, or you could have all the bread you want but the Germans would shoot you afterwards. What do you choose?

To a one, they all said they’d take the bread.

At least then they’d be full when they died.

Nothing besides organs and bones

Wolnerman spent five years being shuttled from camp to camp, horror to horror. Theresienstadt. Dachau.

He caught typhus and waited for death to take him. It took the boy next to him. Wolnerman thought he’d been sleeping, but a guard came into the barracks and threw the stiff body out a window.

He prayed. He survived.

He didn’t notice the German soldiers disappearing in spring 1945, but in hindsight there were fewer and fewer guards at morning count. Then one day, they were basically gone. The nightmare was over, but the struggle just beginning.

In their place came Americans with jeeps full of food. Wolnerman and his fellow prisoners took anything and everything they could grab, unaware that the soldiers speaking in English were telling them their stomachs couldn’t handle that much food.

Wolnerman was 60 pounds, nothing besides organs and bones. And for the starving, saving seems fruitless.

Previously: Holocaust survivor educated in Iowa returns to recount her days at Auschwitz

As he gorged, a soldier approached, asking in Yiddish what this place was, what they were all doing there.

We’re Jews, Wolnerman tried to explain, but really, how do you describe the unfathomable, how do you put words to organized death and suffering on such a monstrous scale.

The soldier took off a gold necklace, the Hebrew word chai hanging from the chain, the Jewish symbol for life.

For you, he said. For life.

Wolnerman put the necklace on, the pendant hanging low on his emaciated frame.

The gift had a double meaning. The chai symbol means life, yes, but it also is used to illustrate the number 18, and Wolnerman would celebrate his 18th birthday a few weeks later. Divine intervention.

“If it wouldn't be for God, I wouldn't be alive,” Wolnerman says. He repeats that sentiment when people ask how he can still be a believer after what he saw, after they killed mothers and babies.

They killed so many, so why does he live? he asks back. There is no reason he should have survived.

No reason, he says, but God.

Life written on his arm

A group of local nuns began feeding the camp’s victims soon after liberation. Every morning, they’d give Wolnerman one more spoonful of oatmeal than the day before. He begged for extra food. Your eyes want more, the nuns said, but your body isn’t ready.

Living in a displaced persons camp in Munich, he met Jennie, the woman who would become his wife. She’d survived by being a female guard’s “favorite,” Wolnerman says, sneaking the extra soup the guard gave her to the bathroom, where she doled it out, spoonful by spoonful, to the other girls her age.

Their love bloomed in the ruins and they built a life amid the remnants of the ones they had before. Wolnerman found friends from his hometown, and they all tried to start over.

He prayed. He survived.

Wolnerman soon discovered the ultimatum given to him years earlier was hollow. His mother, Hanna, and two older siblings, Abraham and Gertrude, all died at camps.

He didn’t know what became of his other sister, Bluma, until years later. By then, he and Jennie were in America, working at a print shop where the German-speaking owner helped the young couple learn English.

Like other survivors, Bluma put notices in Jewish papers or on temple bulletin boards, asking friends to ask friends to ask friends. When she finally found Wolnerman, she told him to move to Indiana, where her husband Josef owned a grocery in Gary.

It was time “to be together,” Wolnerman says.

He joined Josef in the grocer business and they opened an even bigger store in East Chicago, the next town over.

Previously: Iowan who served as U.S. ambassador to Cambodia wins international honor for confronting genocide

Wolnerman worked every day for 42 years, he says, never taking a vacation. His single-pointed goal was to give his two sons, Allen and Michael, the education he never had. He made enough eventually to put both through pharmacy school at Drake University.

For a time in retirement, he and Jennie lived in Miami, where they walked often to nearby cafes for lunch or coffee.

One day, Wolnerman went by himself to try a new spot and a man at the counter greeted him. David?

Wolnerman couldn’t place him, but there was a vague familiarity to his face, his voice. The realization came like a flash — the older boy from the camp.

Show me the number, the man said, and Wolnerman obliged. Ah, yes, 18.

Wolnerman was confused. No. It says 160344.

Add them up, the man said, 18.

Chai. Life. He’d never forgotten the boy with life written on his arm, surely a sign from God in a place where death reigned.

Love amid so many reasons to be bitter

Wolnerman went back to Auschwitz once, in the early 1990s.

His wife came with him, and a friend, too. They took the guided tour for a little bit, but soon dropped off.

They didn't need to learn what happened there. They'd lived those horrors.

Before they left Poland, Wolnerman went back to Modrzejo. He knocked on doors until he found where his gentile friend lived, the one who brought him bread. For years afterward, he’d send a little money to that house, some small way to repay the boy’s kindness.

He prayed. He survived.

His sons had families. His grandchildren grew. He and his wife moved to Des Moines to be near their son, Michael.

His wife started talking about her time in the camps, first to schoolchildren and church groups. People must remember, she said, so that the suffering wasn’t in vain, so it doesn’t happen again.

Wolnerman resisted. He didn’t want to remember.

Jennie was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, and her nurse asked if a few nuns could come over to hear her and her husband's account and pray with them. The one-time meeting became a Friday routine of coffee and cookies, a ritual they continued even when Wolnerman was laid up with a bad flu. On that particular Friday, they traded sweets for oatmeal and took turns feeding him, spoonful by spoonful, he says.

After years of dedicated care, his wife lost her battle with Alzheimer's in 2016. He prayed. He survived. And survived. And survived.

All that survival is what Dr. Chris Haupert, Wolnerman’s ophthalmologist and one of the organizers behind the memorial concert, is hoping to honor. Wolnerman is a “treasure,” he says, and his story should be more widely known.

“When I see David, I see someone who has a lot of reasons to hate people, a lot of reasons to be bitter, a lot of reasons to resent others,” Haupert says, “and, in fact, he's completely the opposite. He's just full of love.

“It would be so easy, I think, to come through something like that and be resentful,” he adds. “Like, 'How could I have been treated like that? If there’s that kind of evil in people, I don't have any trust that there's good.'”

But Wolnerman’s seen what hate can do, to people and communities. He’s felt how it wafts through the air, festering silently and growing like a cancer, unseen and deadly. He didn’t want the hate to rot inside him, so he let go of the bitterness. He forgave — not for them, but for himself.

“My people will be mad at me," Wolnerman says. "How can you? How can you when they kill so many? But I said it’s been so many years. They who killed are not alive anymore.”

He prays. He survives. Prayer, he understands now, is hope in a different form, a way to aspire for a future when your conscious mind can only see endings.

Hints of chai still pop up everywhere, all the time, he says. Like when he took a nasty fall a few weeks ago and was put in hospital room 18. Or when the cold of the necklace the soldier gave him decades ago, one he’s never taken off, touches his chest. A jolt to his system to remind him of life.

Or when he looks at the numbers on his left forearm, as he often does before he takes a breath and tells his story.

He doesn’t see the number they gave him: 160344.

He sees what they’ve always added up to: 18.

He sees life.

The Indianapolis Quartet

Honoring Holocaust Survivor David Wolnerman

7:30 p.m. Sept. 7, Hoyt Sherman Place, 1501 Woodland Ave.

For tickets, visit hoytsherman.org. To learn more about the Indianapolis Quartet, visit theindianapolisquartet.uindy.edu.

Courtney Crowder, the Register's Iowa Columnist, traverses the state's 99 counties telling Iowans' stories. Reach her at ccrowder@dmreg.com or 515-284-8360.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Des Moines' last concentration camp survivor tells Holocaust story