An IRA bomber almost killed Margaret Thatcher. A new book asks how — and why

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

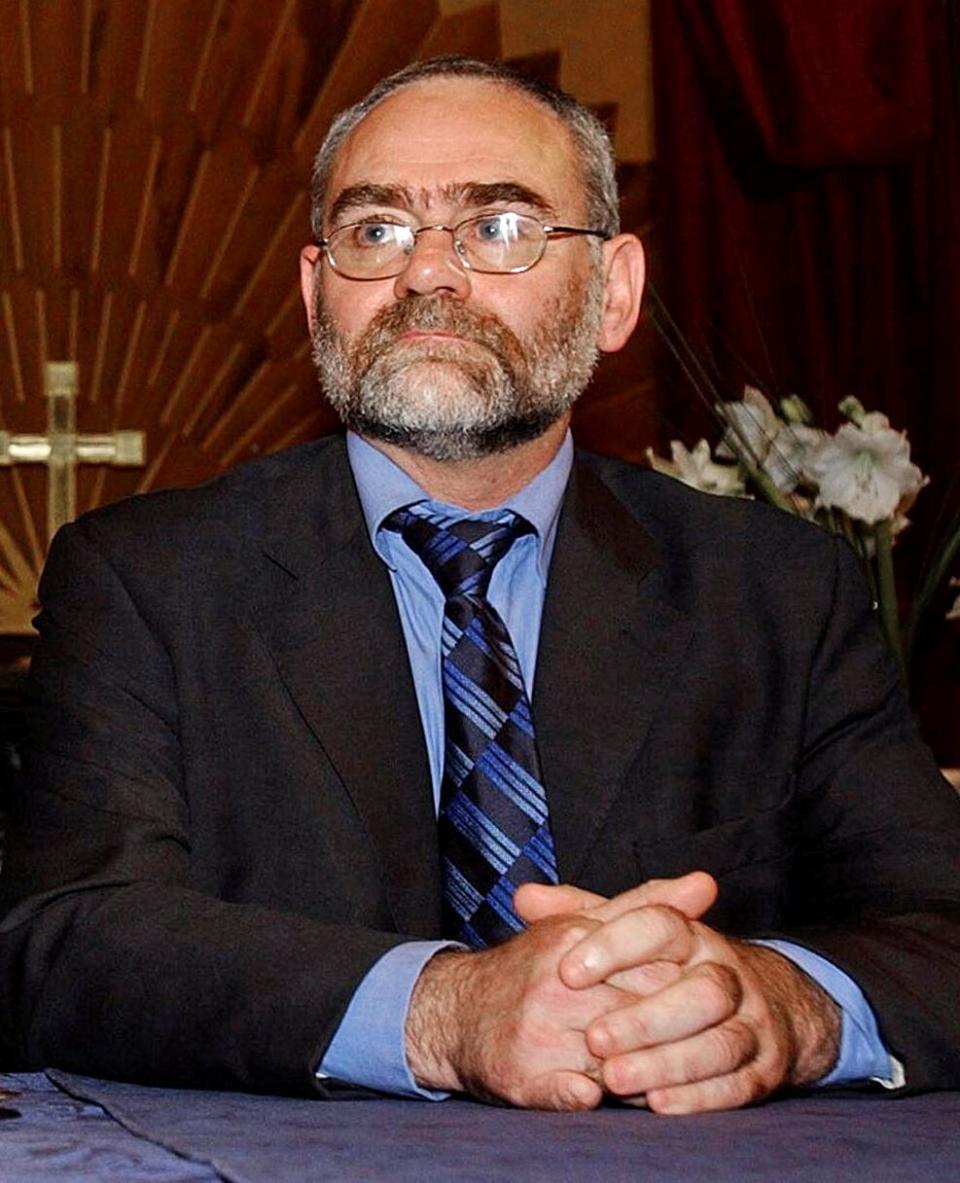

Patrick Magee used bombs to kill people. That much is simple. The more complicated question is whether he was just a murderer or whether the loyal member of the Irish Republican Army was a soldier fighting by the rules of war. One of his bombings — in a Brighton hotel in 1984 — targeted (and narrowly missed) British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. (Five people were killed.) That largely forgotten incident is the heart of Rory Carroll’s new book, “There Will Be Fire: Margaret Thatcher, the IRA and Two Minutes that Changed History.”

Carroll, a Dublin-based journalist, uses the buildup, the event and the aftermath — all of which reads like a classic thriller — to explore the broader canvas of the Troubles, the 30 years of violence that killed 3,700 people and held Northern Ireland, and to some extent England and Ireland, hostage until the Good Friday agreement of 1998.

Though there are cameo appearances by Moammar Kadafi and Whitey Bulger, both IRA supporters, Carroll’s focus is on Thatcher’s government, the bombers and Gerry Adams, the longtime leader of Sinn Fein, the political arm of the movement to unite Ireland. (Adams denies ever being part of the IRA, but Carroll and most journalists and historians insist he was.)

The opening section essentially paints Magee as the protagonist, while later chapters shift to law enforcement and to Thatcher. It’s an attempt by Carroll to grapple with past political violence from every angle at a moment when more of the democratic world seems to be dealing with unrest — peaceful and otherwise — than ever before.

“I’m really trying to be fair to the people I’m writing about,” he explained on video from Dublin. But he has no illusions, expecting the book will anger people on both sides. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Did you shift perspectives because the narrative demanded it or to compel us to see the different sides?

I wanted the readers to enter these different worlds — even within the IRA there were these different subcultures, and likewise with the police and the Tories and the people around Thatcher — to see how they all experienced the Troubles.

It's not about shifting perspectives but about shifting sympathies or empathies. It’s human nature to start siding with the protagonist. I hoped the reader would empathize with almost all the characters, and in some cases root for them. With Magee, you might then find yourself horrified by your own reaction. I’d hope the reader will interrogate themselves to see how their own sympathies shift as the book progresses. Life can be messy.

Does Gerry Adams deserve credit he doesn’t get from the Brits for rethinking the use of violence when others would not?

He really led his people out of a cul-de-sac. History is littered with Republicans and nationalists collapsing into division. It was an astonishing political feat. He was so effective that some people think that he, not John Hume and David Trimble, deserved the Nobel Peace Prize. The rather huge caveat is that he was a key driver of the violence for many years and was implicated in many morally horrendous, unjustifiable decisions. Maybe it took someone like him to deliver the peace.

On the other hand, Thatcher’s mettle right after the bombing is undeniably impressive.

It was, but even more so was her restraint afterward. The IRA was thinking that there might be a hurricane of security forces hunting them down and another round of internment. Thatcher responded to an attack in a very measured way even as the tabloids were calling for her to string them up. She was not brushed off course, and we saw post-9/11 that’s nothing to be taken for granted.

She did a lot of creditable things, but to this day she’s seen as a bit of an ogre in Irish history, so this book might give her a fairer hearing.

The Irish rebellion was always steeped in violence. Was it necessary a century ago to gain freedom from England?

At the time of the Easter Rising in 1916 the rebels were seen as reckless fringe lunatics and they had negligible popular support. But the British overreacted by executing the leaders and then the Irish were so good in romanticizing things with ballads and poetry, and that fuels the founding myths of the modern Irish state. The British would not have left the south of Ireland without the violence. So even if it wasn’t all justified, it was necessary and effective.

But reading about the violence of the ’70s and ’80s in your book, I kept thinking of Stephen Stills’ line, “Nobody’s right if everybody’s wrong.”

I felt the conflict was such a waste. You can ask, “After nearly 30 years of the Troubles, what did everyone get with the Good Friday agreements?” After all the horrendous violence it was something similar to what was offered by the British government in the Sunningdale agreement from 1973. But that was rejected by pretty much everyone in Northern Ireland on both sides.

Everyone was locked into this cycle. There was so much cruelty and grief and the blood continued to flow. For what? I asked Patrick Magee and other IRA men, “What did all that killing do?”

It’s difficult for them to give an answer. The Brits are still there. So it’s questionable as to whether it even advanced the cause of a united Ireland — I think it just alienated the Protestants even more. The Republicans always had a blind spot. They thought, “We just need to get the Brits out of the way and the Protestants will realize that we’re one big happy family.” That was so naive.

Outside of Northern Ireland, how present are these events for the English and Irish today?

The new generations have very little knowledge of or interest in the Troubles. I recently interviewed a dozen undergraduates at Trinity College in Dublin about it. To them it feels dusty and sepia-tinged, like ancient history.

That’s good and bad. It shows the peace process was very successful. There’s political dysfunction, but people are not tormented with headlines of bombs and funerals and can just live their lives. But I do wish people were more aware of what happened and why, so they would not take for granted this imperfect peace.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.