Ira Einhorn, Sixties hippie and murderer who mingled with the great and good – obituary

Ira Einhorn, who has died aged 79, was a former American counter-culture figure who in 2002 was sentenced to life imprisonment for murdering Holly Maddux, a former girlfriend, in 1977.

Her partly mummified body was found by police in 1979 stuffed into a trunk in Einhorn’s Philadelphia apartment; it should have been an open-and-shut case and his story would not have bothered the obituary pages.

Yet the fact that he managed to elude justice for a quarter of a century shed a toxic light on human gullibility, the benefits of having friends in high places, the moral confusions of the hippie era – and the French legal system, which frustrated attempts to have him extradited to the US for several years.

Ira Samuel Einhorn was born in Philadelphia on May 15 1940 and took a degree in English at the University of Pennsylvania where he became active in environmental and anti-war groups.

During the 1960s and 1970s, when he was known as “The Unicorn” (a literal translation of his surname), Einhorn became prominent in the hippie movement. Describing himself as a “planetary enzyme, far-watcher and advance-man for the counter-cultural revolution”, he became the most famous person in Philadelphia.

He led the city’s anti-Vietnam war protests, later switching to ecology and then to parapsychology. He had experimented with LSD in the 1950s, and in the 1960s and 70s he organised “be-ins” and Earth Days.

In 1971 he ran for mayor on a ticket of free love and expanded consciousness, and in 1972 he published a book, a sort of psychedelic poem-rant mixed with apocalyptic photographs and wild graphics. Its original title was meant to be The Marriage of Faust and Shiva, but he eventually called it 78-187880, its Library of Congress catalogue number.

Einhorn got to know most of the key counter-culture figures of the era – Jerry Rubin, Allen Ginsberg, who hailed him as a kindred spirit, Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Garcia, among others.

But many who should have known better also took him seriously. He commanded huge lecture fees, addressing conferences around the world on environmental issues. He taught at Pennsylvania University and Harvard, where he was appointed fellow at the Kennedy School of Government. He won consulting contracts and was paid for his thoughts as a “far-watcher” by leading companies.

His mailing list included multimillionaires and pop stars. The British rock star Peter Gabriel recalled meeting Einhorn in the mid-1970s when he was “involved in some interesting research on Tesla Technology and the paranormal... for which he was seeking funding.”

Despite being hugely overweight, with long hair, a straggly beard, and a marked aversion to soap (he considered himself “too mythic” to wash), Einhorn appeared to have a magnetic effect on women.

In 1972 he began a relationship with Holly Maddux, a blonde Texan hippie. The Maddux family maintained that by September 1977, fed up with his infidelities and controlling ways, she had told Einhorn that their relationship was over.

She had gone to collect her belongings from his apartment in Philadelphia but had disappeared. Einhorn claimed that Holly had gone shopping for tofu while he was taking a shower and had never returned. He then went off on business abroad.

His celebrity status at the time meant that police never considered him a suspect. It was only 18 months later, in March 1979, after Holly’s parents had hired two former FBI agents to investigate, that police finally obtained a search warrant and knocked on the door of Einhorn’s apartment.

Neighbours had told them they had heard sounds of a couple fighting around the time Holly disappeared. They had also complained repeatedly about a nauseating stench emanating from the apartment.

Einhorn, who answered the door in the nude, seemed unperturbed. It was not long before detectives turned their attention to a locked cupboard. There, they found a large trunk containing human remains. “You found what you found,” Einhorn said.

The murder weapon was never discovered, but police concluded that Holly had died from repeated blows to the head. Einhorn was charged with first degree murder.

He would later claim that the CIA or KGB had been responsible for Holly’s murder and had pinned it on him because he knew too much about secret weapons systems, psychic research and global conspiracies.

At his bail hearing a parade of Philadelphia’s great and good – priests, university professors and company directors – testified on his behalf and he was released pending trial, on payment of just $40,000.

But investigations began to reveal another picture. Former girlfriends testified that Einhorn had turned violent when they ended their relationships with him.

Police also read his diaries which contained entries such as: “to kill what you love when you can’t have it seems so natural”, “To beat a woman – what joy,” and “violence always marks the end of a relationship”.

When, a month before the trial in 1981, Einhorn jumped bail and fled the country the sense of shock was huge: “You start to question your whole analysis of everything, ” Stuart Samuels, a former history professor and friend of Einhorn, was quoted as saying. “It depressed me a lot about myself, to be so blinded.”

Einhorn fled to London then Dublin, where he rented a flat from a lecturer at Trinity College and called himself Ben Moore. He frequented the city’s literary gatherings, including the poetry circle surrounding Seamus Heaney who reportedly told police he had found Einhorn “very cultivated, though a bit odd”. He also met Eugene Mallon, a bookshop owner with whom he formed a philosophy study group.

Einhorn narrowly escaped arrest after his landlord became suspicious and contacted the FBI during a trip to the US. Before the Irish authorities could move, however, he had slipped away again.

In 1988 investigators were granted an interview with Barbara Bronfman, a Canadian millionairess who had married into the Seagram drinks fortune and had helped to bail Einhorn.

She admitted that she had continued to send him money until earlier that year. She did not know his whereabouts, but she did give police a crucial name: Annika Flodin, a wealthy Swedish fashion designer with whom Einhorn had begun a relationship.

Following the tip-off Einhorn was traced to Stockholm, but by the time Swedish police came calling, he had vanished once again.

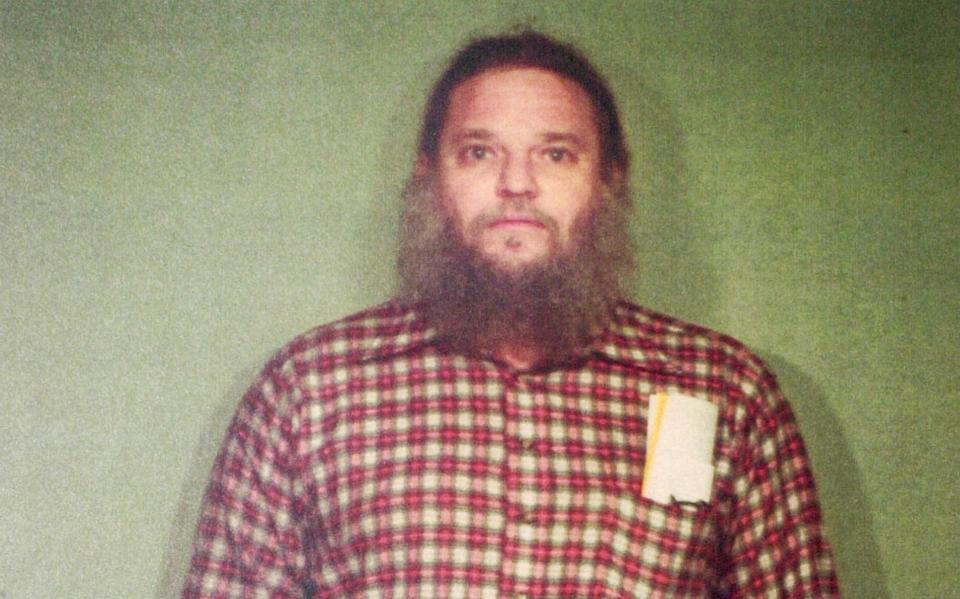

In 1993 the decision was taken to try Einhorn in absentia. It took a Pennsylvania jury less than two hours to find him guilty of first degree murder and he was sentenced to life imprisonment.

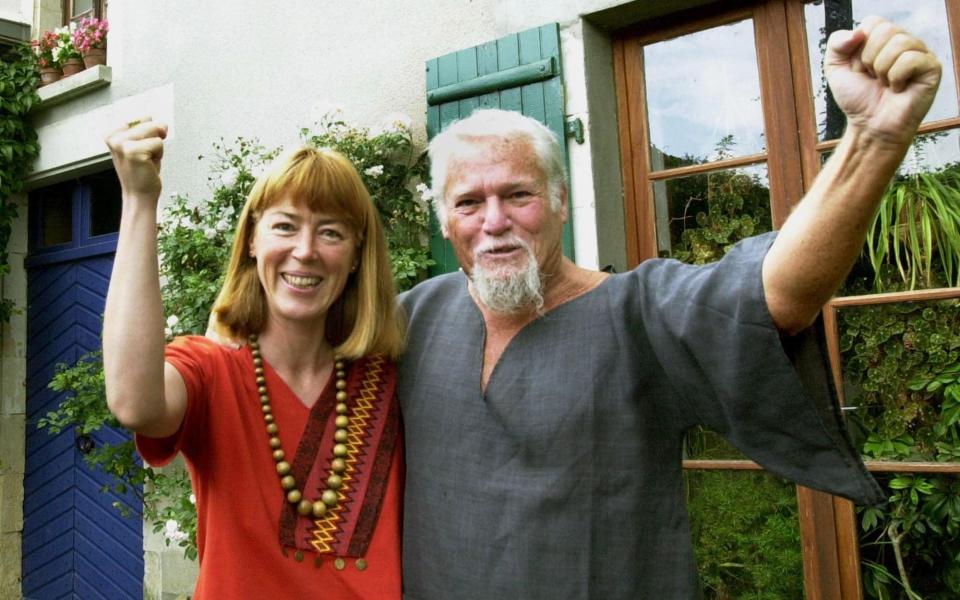

In the meantime Einhorn, now calling himself Eugene Mallon, the name of his old Dublin friend whose birth certificate he had somehow obtained, married Annika Flodin and moved to the Charente region of France where they bought a water mill in Champagne-Mouton.

There, Einhorn passed himself off as a writer of mysteries and an anti-nuclear campaigner, and attracted a following of French hippies who called him Vieux Baba Cool (“Old Cool Daddy”).

The breakthrough came when “Mrs Mallon” decided to apply for a French driving licence, unaware that this required verification from the Swedish authorities. The name Annika Flodin Mallon popped up on a computer in Stockholm, and with it an address in southwest France.

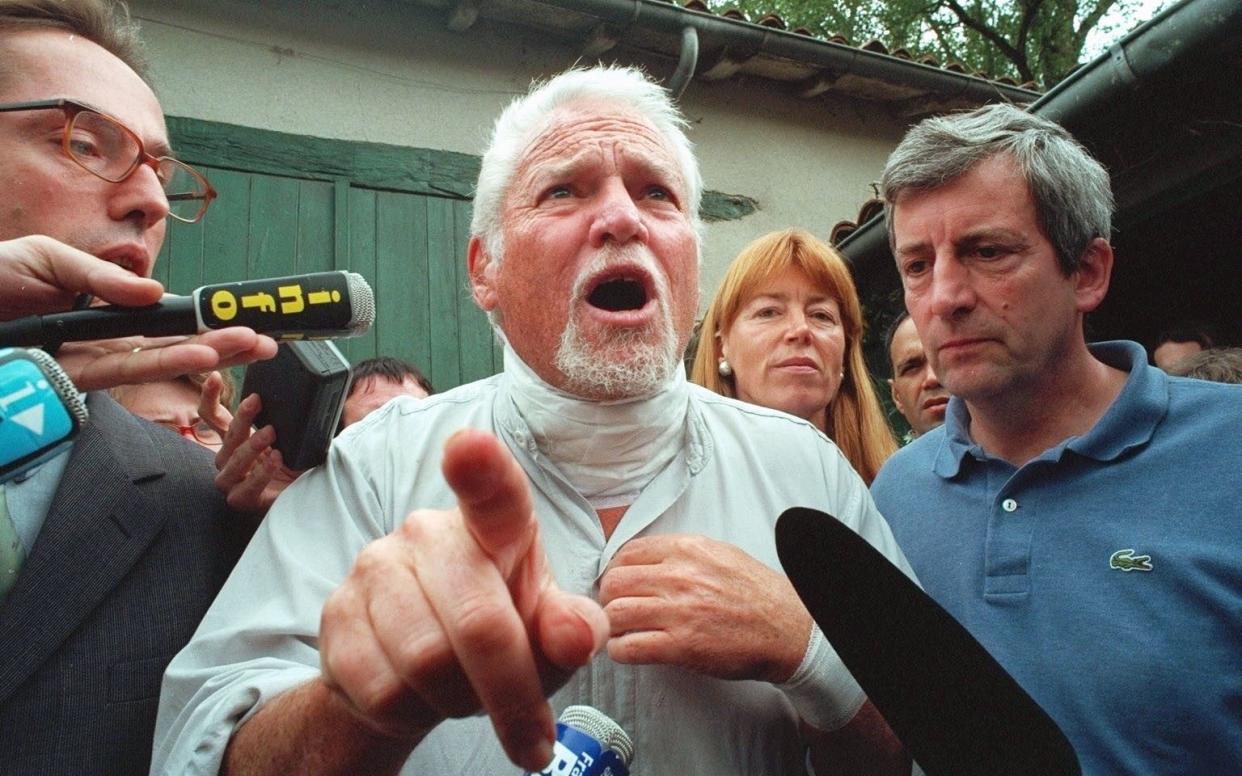

At dawn on June 13 1997 armed gendarmes wearing bulletproof vests hauled Einhorn naked from his bed.

A Bordeaux court first refused to extradite Einhorn on the grounds that, under French law, anyone tried in absentia is entitled to a retrial. Pennsylvania then passed a law promising Einhorn just that. In February 1999, at a second extradition hearing, he was told the conditions for his expulsion had been met – but he was free to appeal.

After two years of further legal shenanigans, in 2001 France’s highest court rejected his appeal, prompting Einhorn to slash his throat, then call in a television crew to record his criticism of France’s prime minister, Lionel Jospin. The European Court of Human Rights intervened, advising the French government that it should suspend the extradition for one week so that it could look into Einhorn’s case.

But the ECHR also ruled against him and on July 20 2001 Einhorn was extradited to the United States.

At his trial in 2002 Einhorn boasted of his connections to Philadelphia high society and claimed he had been framed by the CIA because he had information about mind-control experiments (“psychotronics”) it had carried out in the 1960s and 70s. But the jury needed less than two and a half hours to reach their unanimous verdict of guilty.

Consigned to a high security prison, Einhorn remained intellectually active. In 2012 the Times Literary Supplement described him as “a loyal reader of the TLS and a frequent correspondent”.

Ira Einhorn, born, May 15 1940, died April 3 2020