From Iraq to Nashville: How a U.S. soldier inspired a Kurdish boy to fulfill his American dream

She'd never considered a military career, but Mary Prophit politely paid attention when U.S. Army officers showed a recruitment video during her freshman college orientation.

You can shoot guns and rappel down mountains, video announcers said.

Wait, rappelling? Prophit thought, intrigued. I want to rappel!

When the video ended, Army recruiters went to the window, pointed to a tall building on the University of Michigan campus and said, we rappel down that.

Prophit signed up that day for Military Science 101.

That was the catalyst to her 30-year Army career, mostly in the reserves, which started in 1986.

In 2004 — three years after the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the U.S. — Prophit deployed to Mosul, Iraq, just months after the military captured deposed dictator Saddam Hussein.

She left behind her husband and their four young children.

Humvees and free candy

Ravand Al Dosaki first saw American soldiers when he was 9 — right around the time his mother died.

Like the rest of the boys in the Kurdish city of Duhok, Dosaki couldn't stop staring at the Americans. They were white and Black, not brown like everyone in Iraq. They had big guns and drove in cool Humvees. And soldiers often gave the Kurdish children candy or their Meals Ready-To-Eat (MREs).

Best of all, the boys' parents said the Americans were here to save them all from Saddam.

"I got even more excited!" Dosaki said.

But he didn't rush the soldiers and pester them for money and food like the other boys did.

"I didn't want to bother the soldiers," Dosaki said. "I felt like Kurds often made them uncomfortable."

Dosaki laid back and watched, eventually, tentatively, joining the soldiers when they would sit down and try to talk to the local children. He picked up a few words of English, and he liked the candy.

A year or so later, Dosaki, third oldest of 11 brothers and sisters, dropped out of school to try to bring home food and money for his family. His father worked long hours at a Kurdish soda-making plant — "our soda tasted better than Coke!" — but it wasn't enough to support the large family.

At 10, Dosaki started getting gum and food on credit from local shop owners and selling his products in the streets and around bazaars. He, too, eventually started approaching American soldiers, who paid in U.S. dollars, worth much more than local currency.

One day, he saw a woman soldier, with blonde hair, and she seemed kind. At first, the boy was too shy to approach her, even though she kept staring at him.

Soccer balls and a sweet boy smoking a cigarette

Prophit was assigned to a civilian affairs liaison unit in Mosul, so her job was, through interpreters, to make connections with local Iraqis. But Al-Qaeda was active in the area at the time, making her task even more dangerous and difficult than usual.

A major tool she used to make connections — soccer balls. She would give them away to start conversations. And she could find and buy soccer balls about 90 minutes away from Mosul in Iraq's Kurdistan region, in a beautiful valley city called Duhok.

There, groups of about six boys, ages 9 to 13 or so, would run up to the soldiers: "Mister, mister, give me money. What do you need?" The soldiers got nervous because the kids got so close, but the Americans would give the boys a dollar or two each.

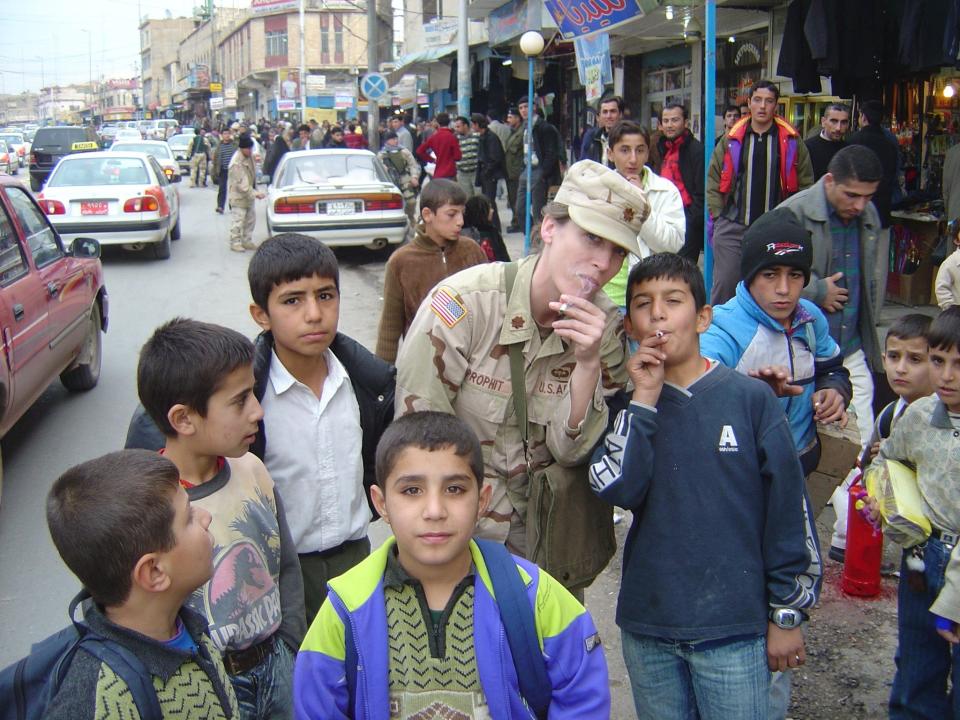

But Prophit saw one boy with a sweet smile who always kept his distance. "I noticed because he was just watching, not tugging on us," she said.

Then one day, she saw that sweet boy smoking in the market. Her first words to him: "What are you doing? You need to quit smoking! It's an awful habit."

The boy smiled at her, not understanding anything she was saying. Prophit grabbed a cigarette from a soldier and, as a joke, lit it and started waving it around the boy, even posing for a picture while they smiled and laughed.

She tried to talk to the boy, who knew a few dozen or so English words. Prophit heard him say his name was Rovan, and she called him "my little Rovan" from that on.

"Every time I was there [in Dohuk], I was drawn to him — he was so sweet, and he had this smile, and he never ever asked for anything like the other kids did."

And he tugged on her mama heart strings.

"I was feeling very maternal to him," Prophit said, "because he was close in age to my own kids whom I was missing tremendously."

'She was like a mother to me'

Dosaki didn't need money from the Army officer because, by then, he had a booming business of selling DVDs to the Americans. Besides, the 11-year-old got something better than money from Prophit, something he very much missed at home — maternal affection.

"I had big big feelings for her. She was really nice, and I could tell she’s watching out for me," Dosaki said.

"She gave me toys to take, and she had a kind heart. She was like a mother to me."

Dosaki continued to learn more English, and he became a sought-after guide and translator for U.S. troops coming to Dohuk. The boy often spoke with translators embedded with the Army.

Already dreaming of going to America one day, Dosaki, around 2010, sat down with a translator who encouraged the boy to go to the U.S.

"He was telling me that America’ s different, there's water and electricity 24 hours a day, seven days a week, that kids like me don’t work on the street, they go to school. He told me, 'If you can come to America, it’s gonna be better.'"

The boy knew in his heart that the translator was right.

He saw Prophit five times during her first year-long deployment to Iraq. And, without explanation, he stopped seeing her. For years.

The longshot paper copy of a picture

Prophit never got the chance to say goodbye to her little Rovan before returning home in June 2005. She thought of him often for the next several years, but she had no way to reach the boy.

When she got orders to return to Iraq in 2009, Prophit immediately thought she needed to figure out a way to get back to Dohuk and see the little boy, who by now was 16. Within weeks, she heard of a U.S. diplomat about to go from Mosul to Dohuk for a meeting. So Prophit printed out a 4-year-old picture of herself with her little Rovan and caught a ride with the diplomat.

Once in Dohuk, Prophit sat outside the building holding up the picture and asking any teenager or young man if he recognized Dosaki. There was little foot traffic, and for hours, no one recognized the 11-year-old in her picture.

And then, one young man did. "He seemed to study the picture. He didn’t come across as a kid who wanted a buck."

Prophit quickly wrote down her cellphone number and email address on the back of the paper copy of the picture and handed it to the young man. Please get this to my little Rovan, she said, thinking it would never happen.

But two weeks later, in the middle of a meeting in Mosul, Prophit's phone rang with an unfamiliar number coming out of Kurdistan.

"It's me, Rovan," a teen boy's voice said in fluent English.

"My little Rovan!" Prophit nearly shouted back.

The two reunited within weeks, and this time, Prophit got to meet lot of Dosaki's family, including Dosaki's father and several siblings. Prophit even arranged a four-day vacation of sorts in Dohuk, and she and Dosaki spent lots of time together, sight seeing and going to restaurants and hookah bars.

Dosaki had secured work with American companies, helping train Kurdish police and doing other security type work, always helping U.S. troops when Dosaki could.

Prophit worked hard to secure a U.S. visa for the teen, and Dosaki's father even agreed to sign away parental rights if it would help get his boy to America. But those efforts failed, in large part because Dosaki, 16, needed to be 18 to get into the U.S. without a parent, Prophit said.

"I tried so many times, but it just didn't work," she said. "Saying goodbye to Rovan on Jan. 25, 2010, was undoubtedly one of the hardest things I ever had to do."

'It represents the hopes we soldiers had'

Dosaki kept working for U.S. companies in Kurdistan, and finally, at 23, he secured a work visa to come to the U.S. He met a Kurdish friend in Louisville, Kentucky, where Dosaki took canine security training in 2017,

Months later, Dosaki heard about the large Kurdish community in Nashville, moved here, met his wife, Vammon, at a Kurdish wedding, and started working in restaurants, including House of Kabob, which is owned by his wife's family.

Prophit, who'd recently retired from the Army, visited Dosaki shortly after he moved to the U.S., a very emotional reunion for both of them.

"I initially met him during my first deployment, and I saw lots of combat, I saw a lot of s***. To meet a child during that time and then later miraculously find him again?" said Prophit, a Michigan native who now lives in Washington state.

"And then to see him safe in the States in a Kurdish community, this was full circle and a sense of closure for me. He represents so many people we met along the way who captured our hearts. To see him in person in Nashville, it represents the hopes we soldiers had that we were doing some good in that region."

Dosaki knows Prophit is sad she couldn't directly secure his entry into the U.S. But he and his wife credit her for getting him to America.

"It was crazy to see Colonel Prophit in the U.S.," Dosaki said. "But I knew it was going to happen and it's because of her.

"She gave us hope and faith and kindness and love. She made me feel like I belong in the U.S. She's the reason I'm here."

'All the dreams came true'

Since moving to Nashville and getting married, Dosaki and his wife had their son, Alan, now 4. Dosaki started driving for ride share services as much as 18 hours a day, falling in love with meeting and talking with so many different kinds of people.

He started buying better cars so Dosaki could give premium rides, and in 2020, Dosaki and his wife started their own luxury limousine service, TNLimousines.com, a.k.a. Ravands Private Rides LLC.

Dosaki owns seven vehicles, and he pays his drivers $25 an hour, and they keep all tips. He often financially helps relatives and Kurds in Nashville and all around the world, responding to needs that pop up in phone calls or one social media.

Dosaki said it's important to pay forward his success, to model the kindness Prophit showed him.

"All the dreams came true," he said. "I want to help others who grew up like me."

His latest dream come true: Dosaki was sworn in as a U.S. citizen along with 59 others from 32 countries Tuesday, Oct. 24 in Nashville's federal courthouse.

That allows him to vote in U.S. elections and it gives him more of a sense of security about visiting his family in Iraq and being able to return to Nashville.

"That is the best feeling ever to become a United States citizen. I was so happy and excited in the heart," he said moments after the ceremony ended. "I'm so proud of it."

Prophit, who has visited "my Kurdish son" three times since he moved to the U.S., remains close with Dosaki and is intensely proud of his journey and his U.S. citizenship.

"He is proof that of all the awful things happening in this country," Prophit posted recently on Facebook, "it is still the land of opportunity if you are willing to put in the work. I am so insanely proud of him and his journey."

Reach Brad Schmitt at brad@tennessean.com or 615-259-8384.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: From Iraq to Nashville: How a Kurdish boy fulfilled his American dream