It isn't a holiday without my mother's family potato balls. If only she agreed

We open on my son Abe. He’s 2, seated in a high chair, and his hands are covered in flour and a sticky dough.

“What are we making?” I ask, off-camera.

“Potato balls,” he says, testing out his then-new words.

The rest of the iPhone video documents my mother’s bustling kitchen on the eve of the big holiday meal. My other son is eating Cheerios, but my father and sister are making the family version of kartoffelklösse, the German potato dumplings my sister and I have cherished since we were kids. She’s dropping rounded balls of a simple dough — boiled potato mash, egg, salt and flour, kneaded together and then rolled into spheres the size of shooter marbles — into a stockpot of simmering water. My father is tending the boil with an old enamel skimming spoon, pulling the dumplings from the water once they float to the top and (in the classic family test of doneness) “wiggle-woggle” there for a bit.

At one point I pan to my mother, seated by the window. “Mom, what are you doing?” I ask, in faux-documentary mode.

“I’m cool as a cucumber,” she says, not participating, looking amused.

Off-camera, my sister laughs. The joke is that she’s not at all cool.

Every year, the potato balls are a struggle. My sister and I can’t imagine not making them. But my mom — even though the recipe is from her family, the flavors from her childhood, the tradition ostensibly hers — resists.

The potato balls are a production. At least a day ahead, we boil the russets and Yukon Golds. Then we make the dough and cook the dumplings. We debate whether the flour we’ve used is sufficiently “scant” (too much makes the dumplings easier to roll but gluey to eat) and whether we’ve used enough salt (my mother always thinks no). We mix and roll with our hands, so we leave sticky residue on every kitchen knob, where it hardens into sharp crags.

Once that mess is clean, there’s more. Just before dinner is served the next day, we haul two old electric skillets onto precious counter space and slowly sauté the dumplings in butter until they’re a perfect crispy golden brown.

“Do we really need to make them?” our mom will say. “Maybe we could just skip it this year.”

“No!” we’ll cry.

There’s never any doubt that the potato balls will get made. But the tension is real — and as much a part of the tradition now as flouring our hands to roll the dough. My father became a master at navigating it. He’d sneak out to buy the potatoes ahead of time, handle the boiling and mashing before my sister and I got in. He’d contrive to usher my mother up to bed and then stay up late with us, always the best at rolling — his dumplings, like any present he wrapped or peanut butter sandwich he made, were painstakingly uniform and precise — and always cleaning up behind the whole maelstrom so the house would be guest-ready in the morning. Like a traffic conductor, or a toreador, he found a way to guide the strong-willed women in his family safely past each other.

I found the potato ball video after my father died last year, of cancer, and I loved getting to hear "wiggle-woggle" in his baritone once more. What struck me when I watched it again recently, though, was my mother. She was cool as a cucumber — and she wasn’t. Resistant, but resigned. Why do we always fight about the potato balls? We’ll be making them again this Christmas, without my father, assuming my sister and I have our way. It suddenly seemed urgent to find the answer.

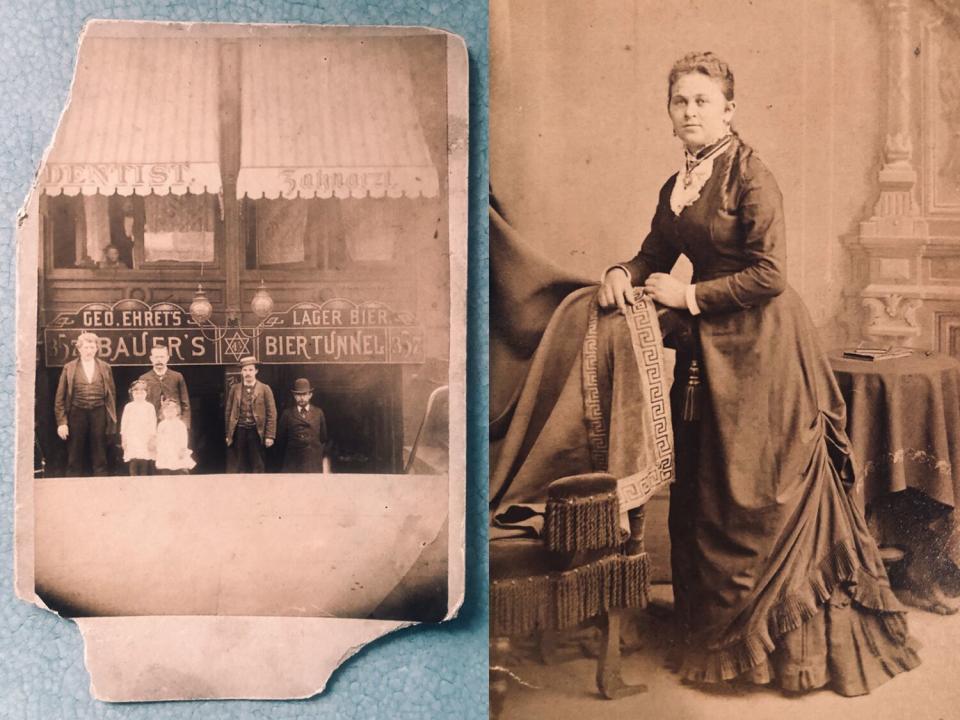

Growing up, she said, when I reached her by phone earlier this month, kartoffelklösse weren’t on the Christmas or Thanksgiving menu. They were made to accompany sauerbraten, which was its own occasion, served with red cabbage and creamed spinach, two or three times a year. The recipe came from her great-grandmother, Julia Reis Bauer, who was born in New York state in the 1860s, the daughter of German immigrants. She was a mother of six, a great cook and a businesswoman who, with her husband, ran a rathskeller on the Bowery, Bauer’s Bier Tunnel, where she served German food for many years.

Also, my mother said, the potato balls weren’t fried. They were served fresh out of the boiling pot, “with croutons on them.”

This was shocking news.

The whole point of the potato balls I grew up with — and the reason my sister and I fight so hard each year to get them made — is the glory of their texture. In a good year (and potato balls have vintages, each batch with its own character, some years especially fine; eventually we started keeping a journal to track minor variations in technique) the interior is flavorful, salted and eggy and light as a cloud, and the exterior is a thin, crispy carapace of golden brown. It’s like eating a spherical French fry.

“They’re just so delicious,” my sister said, when I called and asked her why it was, in her view, “not a possibility” to let our mom put the kibosh on the kartoffelklösse. “They’re buttery and hard on the outside but soft in the middle. They’re just the bite you want on the plate.”

I’d always assumed the deliciousness my sister and I so prize was a classic German delicacy. That if I ever made it to Berlin, I’d be drowning in crunchy, potato-y delights. A soggy, dense dumpling covered in croutons was something else entirely.

Research reveals a vast universe of German dumplings, none quite like the ones we make. Mimi Sheraton’s “The German Cookbook” lists 23 types of dumplings and noodles prepared as garnishes for soups and stews; only three are made of potato, and each of these has croutons pressed into the center of the dumpling. (Two are served with breadcrumbs on top; none are fried.) Karen Lodder’s “Easy German Cookbook” features a croutonless version, though it uses nutmeg and corn or potato starch, and again, nothing is fried.

When I asked Lodder about our unusual recipe, she noted that she’s familiar with recipes for potato balls with and without the bread cube center. “As for frying them, which sounds freaking delicious,” she added in an email, “a possibility is that they are making a hybrid of schupfnudeln.”

Sure enough, the schupfnudeln recipe in another chapter of Sheraton’s book is closest to our own. The ingredients are the same and the dumplings are boiled, cooled, then fried. The difference is the shape. Schupfnudeln are long irregular fingers, not perfect golden spheres. It’s not a word I ever heard my grandmother use, but somewhere along the way she and her family’s cooks must have adapted the technique.

My aunt is 15 years younger than my mother, so her childhood was distinct: early ’70s, not late ’50s. She also remembers potato balls served with sauerbraten. In her memory, the potato balls were a sop to her limited palate.

“I didn’t like anything. I wanted ice cream for breakfast. Sauerbraten?" she recalled. "Sour boiled meat, not so good for me. So I’d probably have like 15 to 20 potato balls. And that was my meal. ”

The potato balls my aunt remembers were fried. Perhaps the innovation was a way of enticing the picky eater to the table. She remembers her mother would say, "‘Julie, shake the pan.’ And I’d have to go and make sure they were all rolling over and evenly, perfectly brown and crispy.”

My mother allows that fried potato balls eventually made their way onto the table. Sometimes they were part of her birthday meal, served alongside roast beef. But the question of how they became a must on our holiday menu — Thanksgiving is when they are essential for my sister and me, although we’ll make them for Christmas this year, since we’ll be together — remains. Why are my sister and I so adamant about a custom my mother doesn’t prize?

Then my mother asked me the question I’d been asking her — when do you first remember making potato balls? — and we found the answer: my grandmother.

She was a vivid person with sparkling eyes, able to plug in immediately to the true emotional currents of whomever she was talking to. She never left a bus ride without a brand-new friend. She moved down the street when my sister and I were in elementary school and was a frequent babysitter. Cooking projects abounded. We made oatmeal lace cookies and linzer torte. And we made potato balls.

I remember her kitchen covered with flour. Long discussions of whether to crack the eggs directly into the potato mash or lightly beat them first. Hands covered with goo, and dramatic concern about whether we’d overfloured the dough. Anticipation as we watched the dumplings “wiggle-woggle” — never any other verb — letting them jounce at the top of the boil until they looked ever so slightly fluffy, at which point we scooped them out.

When she got older, we moved the operation to her assisted living facility, where my sister and I overtook her galley kitchen while she directed us from her recliner chair. We’d bring samples for her to test. “Ooh,” she’d squeal with particular satisfaction whenever they tasted just so.

No wonder my mother feels bewildered by our fixation on Thanksgiving potato balls. She’s right. It isn’t her tradition. It’s an entirely new one we invented with her mom.

On the phone with my mother, I ask her, “Do you think potato balls are delicious?”

“I do,” she says, laughing, “when they have enough salt.”

My mother loves to embark on kitchen mischief with my sons. Once they made a baked Alaska, doused in brandy and set ablaze. Once they cut up my father’s less-nice neckties and used them with vinegar to dye Easter eggs. Whenever they’re together, they make fresh orange juice. This Christmas, they’ll get to make it for the first time with the fruit of the newly planted orange tree in our California yard.

I’m struck by how the rituals shift and change. How the unfried dumplings and sauerbraten were a taste of German roots for my great-great-grandmother Julia and her kin. How the frying, which probably began as a way to juice up leftovers, became part of the core preparation when my aunt was young. How the German classic became something new. How my grandmother helped my working parents by taking care of my sister and me, conjuring a fresh tradition from an old one as a way to entertain us.

My boys don’t (yet) like potato balls, though every year we try, and this year, even without my dad around to conduct traffic, we’ll try again. Perhaps in 10 years the boys will insist we can skip the kartoffelklösse but must have baked Alaska. And I’ll be the one who’s “cool as a cucumber” as I watch them in the kitchen, playing with fire.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.