Israeli-Palestinian conflict tests relationship between Black, Jewish Miamians

Phillip Agnew’s 2015 trip to Palestine forever changed his view of conflict in the Middle East.

There, the prominent Miami-based social justice advocate saw what he describes as “cold, calculating racism and ethnic cleansing” by the Israeli government: checkpoints that divided mosques; markets with overhead netting to protect Palestinians from having feces or urine thrown on them; a mother who lost her unborn child when Israeli police gassed her home after she refused to leave.

“I did not see a conflict; I saw full-on military force with the backing of Europe and the United States put upon people who, at most when I was there, were throwing rocks,” said Agnew, 35, who compared the Palestinian experience to that of being Black in America. “To me, there isn’t a side: there’s right and there’s wrong, there’s the empire and the oppressed.”

Agnew’s perspective represents one view in a growing divide between South Florida’s historically aligned Black and Jewish communities — a rift that local leaders are struggling to keep from becoming a chasm.

Many Black activists — especially those who are younger — view the recent spate of violence between Israel and Gaza as the product of an illegal occupation where human rights violations occur daily. Many who are Jewish align themselves more closely with Israel, a longstanding U.S. ally that, they argue, has a right to defend itself against rockets fired by Hamas terrorists.

In Miami, where the alliance between the city’s diverse coalition of racial and religious groups has borne fruit since the Civil Rights era, there are already signs that a unified front has begun to deteriorate. Social media chatter has become more polarized, political alliances are fracturing and local police report alarming clashes between supporters of Palestine and people of Jewish faith and heritage.

Elder statesmen and religious leaders hope communication can help. But some say merely talking about the conflict has become difficult.

“It’s such a tough and charged conversation that folks are reluctant to talk about,” said Matt Anderson, executive director of NCCJ, which has a long history of diversity, inclusion and social justice initiatives in Miami.

From the Middle East to Miami

Tensions brewing for decades in Jerusalem reached new levels in early May as Israel and Hamas militants traded missiles. A cease-fire was recently announced to end the bloody 11-day stretch. The violence led to the deaths of at least 230 people in Gaza, including 65 children, and 12 people in Israel, according to news reports.

The conflict reverberated across the globe. In Miami and Fort Lauderdale, people passionate on both sides of the issue — those who support Israel’s actions and those who condemn it — have taken to the streets and to social media.

The Greater Miami Jewish Federation, which has partnered with groups like the NAACP and the Coalition of South Florida Muslim Organizations, said this time, the conflict in the region — and the reaction locally — has felt different. Josh Sayles, the Federation’s Director of Jewish Community Relations and Government Affairs, said the group hasn’t seen support from all of its partners that it has in the past.

“It really hurts and it’s a scary issue for us,” he said, speaking about those who don’t stand up against anti-Semitism and social media campaigns that describe the conflict from one point of view. “What Jewish people are accused of standing for is not factually accurate. The narrative is being distorted in nasty, horrible ways.”

Rabbi Eliot Pearlson, of Temple Menorah in Miami Beach, attributed the tension to extremism on both sides of the conflict, noting that even finding members of different groups to serve on panels together is getting “harder and harder.” He said if there is going to be peace in both American communities and the Middle East, it has to be accomplished by individuals, not governmental entities.

“Seldom, historically, have governments or politicians ever really made real peace,” he said.

Anas Amireh, president of the South Florida chapter of Al-Awda, also known as the Palestine Right to Return Coalition, said everyone is trying to live peacefully together. “But when [conflict] erupts, emotions are high. We can’t, in this day and age, have an entire people under occupation and pretend nothing’s happening.”

Pearlson, the Temple Menorah rabbi, noted a recent rise in anti-Semitic incidents which, according to ADL Florida, has shown a 40% increase in 2020 over the previous year. Just recently, Miami-Dade’s Bal Harbour made news when a Jewish family visiting from New Jersey was targeted by a group of men who, they said, hurled insults and trash out the window of their SUV while claiming to support Palestine.

Gabriel Groisman, the village’s mayor, has been outspoken in support of Israel and firmly believes the conflict in the Middle East is rooted in anti-Semitism, not land or government. Groisman, who is Jewish and a self-labeled Zionist, says while there will be efforts to bring people together, theorizing that there could be an end to the conflict right now is “utopian and unrealistic.”

“Those who want you to cease to exist ... you’re not going to be peaceful with them,” he said. “The reason why Jews don’t fit in any category of race or nationality is because we have been driven out of anywhere we have ever lived.”

In front of a digital billboard that showed American and Israeli flags, Groisman took the stage at a “Defend Israel” rally last weekend in Hallandale Beach.

“Israel represents the resurgence of Jewish strength and Jewish pride.”

From today’s Defend Israel Rally in South Florida. Full speech at: https://t.co/Y4XWI0W53I pic.twitter.com/0iGehGyUdA— Mayor Gabriel Groisman (@GabeGroisman) May 23, 2021

“Israel is the symbol that the Jewish people will never again be victims of hate, of anti-Semitism, of the Holocaust,” he said into the microphone. “That is what the soldiers of the Israeli Defense Force mean to us.”

A Generational Divide

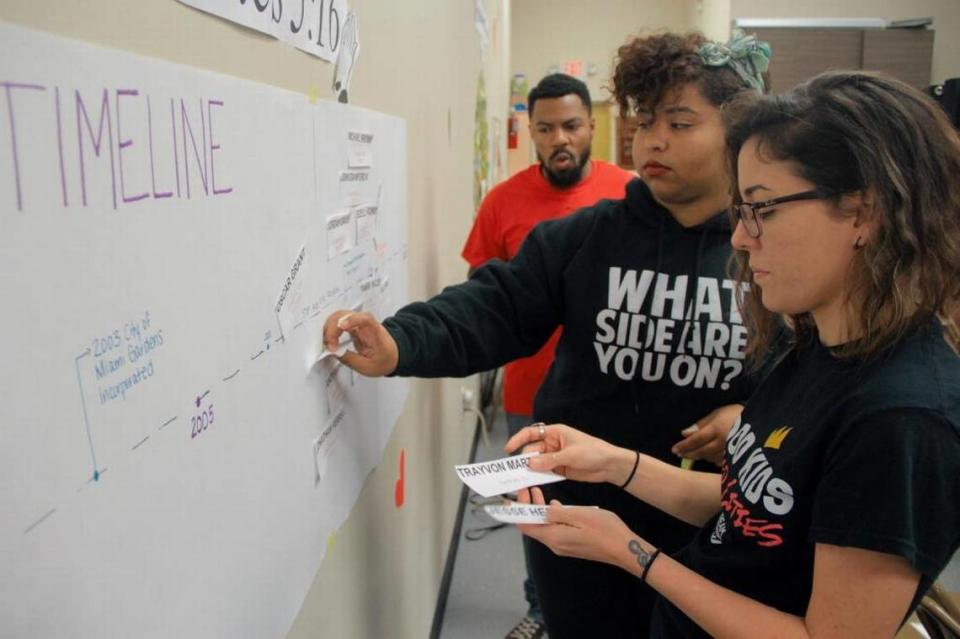

But critics, many of whom tend to be Agnew’s age and younger, see Israel’s symbolism differently. In their eyes, the Israel of today has more power than ever — thanks in part to $3.8 billion in annual military and defense supplies from America — and exercises it with impunity. It’s one of the reasons why The Roots Collective, a Liberty City-based grassroots organization dedicated to building economic sustainability in Black and brown communities, was quick to create “Free Palestine” T-shirts.

“Solidarity!” Isaiah Thomas, one of The Roots Collective’s co-founders, said via text when asked what prompted the shirts. “We understand how it feels to be displaced from a place you feel like is yours and to be aggressively policed like you’re doing something wrong. Those are the realities throughout Black America and in Palestine.”

The South Florida Chapter of Jewish Voice for Peace, a liberal anti-Zionist organization, has also fielded calls from young people in search of different viewpoints from what they were taught growing up Jewish in America, one member, Donna Nevel, told the Miami Herald.

She believes the sentiments around anti-Semitism are sometimes misleading, and that Jewish people like herself can criticize the government and still be what she calls “an ethical Jew.”

“I believe anyone with a conscience, any Jewish person who studies what it means to be an ethical Jew, cannot sit quietly while Israel is so violent,” she said. “You can’t continue to get away with propaganda that says Israel is victim, when Israel is the aggressor.”

Prior to the most recent eruption of violence between Israel and Hamas, the conflict had increasingly become an issue in domestic politics as progressive activists picked up Palestinians’ cause as a matter of human rights. In the Democratic Party, where Black and Jewish voters are both key constituencies and young progressives have fueled grassroots campaigns, disparate views on Israel and Palestine have festered just below the surface for years.

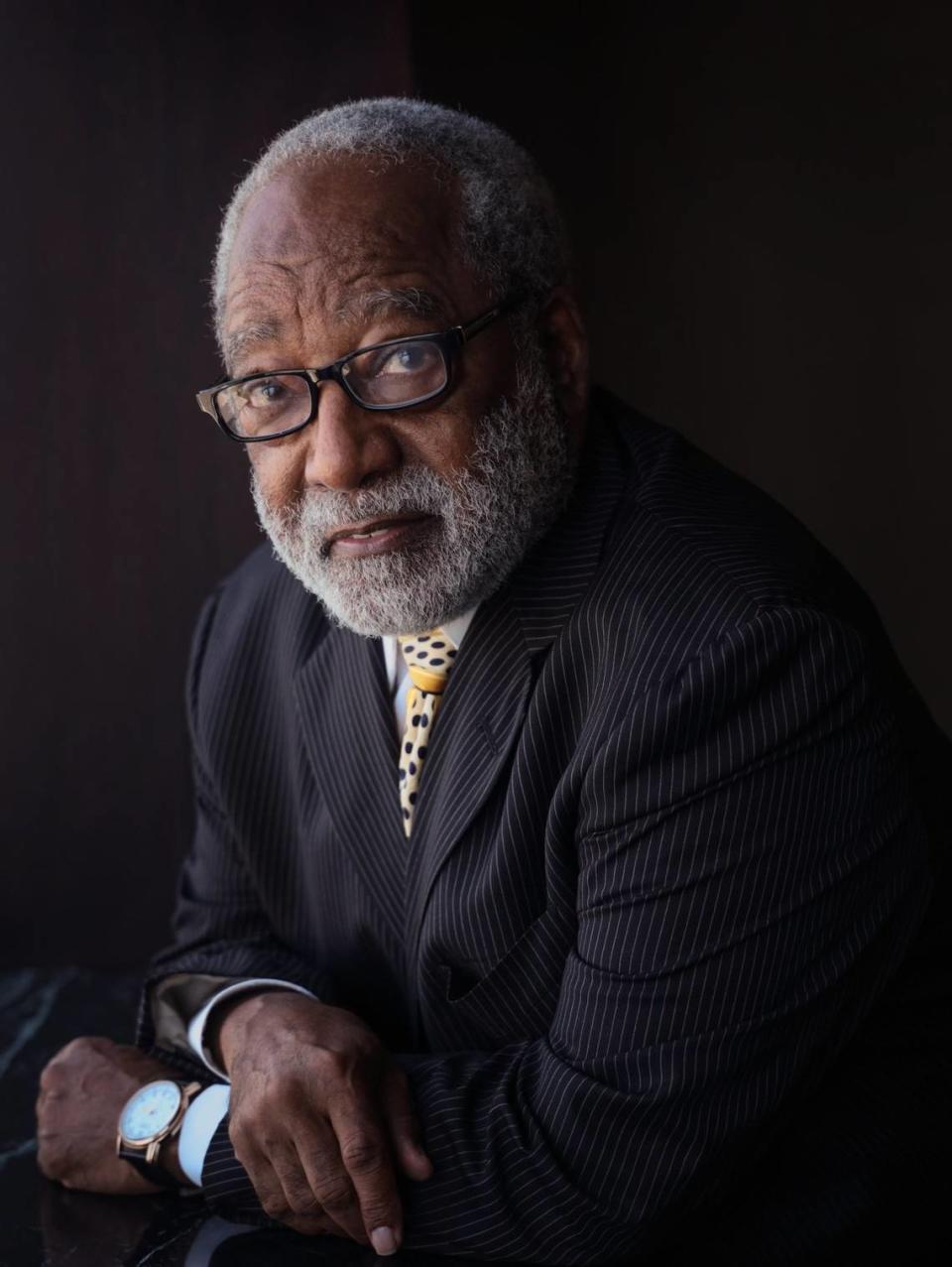

H.T. Smith, a veteran Black civil rights attorney from Miami, said he worries that while Blacks and Jews of his generation still have strong bonds from decades in the trenches on civil rights issues, younger generations lack a common cause.

“I can understand young Black people are seeing the Palestine situation being similar in nature to the experience that Blacks have had in America,” Smith said, “but they should know Jews are not our enemy.”

Stephen Hunter Johnson, chairman of the Miami-Dade Black Affairs Advisory Board, said people have become more sensitive to the plights of oppressed people across the globe, but firmly dismissed equating the Black community’s fight for freedom with that of the Palestinians.

“I think the biggest difference is this: in our entire march for freedom — and we’re not there yet but we’re still marching — our hands have been at our sides,” he said, contrasting largely peaceful protests with Hamas’ use of rockets.

A supporter of a two-state solution, Hunter Johnson takes issue with organizations like Black Lives Matter being so quick to support Palestine. Doing so, he warned, puts the Black community at risk of losing a major ally in the American Jewish community, warning that some criticisms can be deemed anti-Semitic.

“The idea [of a revolution] is to remove the shackles from your feet and march on,” Hunter Johnson said. “We still got shackles on our feet. How the hell do we look trying to unshackle somebody else?”

Pose that question to Agnew and his answer is rooted in a Black Panther ideology that views the struggle for liberation as international rather than confined to American borders.

“For us, it’s a matter of creating and nourishing international relationships and alliances because, frankly, we’re going to need people in other countries to really stand up alongside Black, poor, Latino, indigenous people in the United States,” said Agnew, who last year was a senior adviser on U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign.

That’s not to say American Jews aren’t welcomed. Quite the contrary says Agnew, who sees the ongoing conflict as the very situation that can yield a stronger bond between younger generations of Blacks and Jews.

“We’ve entered into an exciting new chapter about what happens when Black people and Jewish people in the United States don’t just work for the betterment of the lives of Black and Jewish people in Miami or in South Florida or in Florida or in the United States, but around the world,” he said. “If that history is so righteous and treasured, then it will only grow and expand. Let’s spread the good news about what Black and Jewish people can do for Palestinians, Jewish people around the world and for other people who don’t look like us.”