From Ivory Coast refugee camp to Amarillo, the story of former Tascosa standout Chris Doerue

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the early hours of Sept. 19, 2002, military troops across the Ivory Coast staged a coup in an attempt to overthrow the government. The rebels launched attacks throughout the nation, overtaking the cities of Bouake and Korhogo.

This was the beginning of the First Ivorian Civil War, which resulted in the country being split in two for the next eight years. The violence spread throughout the country, causing many citizens and refugees of other countries to flee.

The Doerues were one such family.

Augustine and Annie Doerue, along with their children, left for the United States in 2004. They settled in Amarillo, where the children all found a love for sports.

For their son Chris, that sport was basketball.

Chris wasn't the only Doerue child to develop a love for the hardwood, but he may have been the most gifted. He was an outstanding defender with a work ethic that coaches dreamed of.

Those traits helped him develop into a standout guard for Tascosa High School, where he became a starter for one of the most successful teams in program history in the 2015-16 season.

“He was short statured," Tascosa coach Steven Jackson said. "He wasn’t a tall kid, but he was one of the most athletic kids we had. Fast, quick, strong, a deceptive athlete.”

Jackson went on about the kind of person Chris was off the court. Chris' older brother, Junior Doerue, did the same. They both talked about how positive and encouraging he was as a young man. Those traits and his success on the court eventually led Chris to a college scholarship en route to an associate's degree in criminal justice.

Junior said Chris, "wanted to be FBI."

Before that, Chris worked with kids at basketball camps, training his nieces and nephews as well as first and second graders about athletics. There was even talk about him going back to school to earn his bachelor's degree.

All of that alone is rather remarkable when put into context.

Born in a refugee camp, family fled a civil war, earned a basketball scholarship to college, worked with kids and had dreams of working for the FBI. Chris Doerue, and the whole Doerue family, truly seemed to be the embodiment of the American dream.

To top it off, he managed to do it all while getting along with everyone.

"Chris didn’t have friends, he had family," Junior said. "To him, all the people around him were family. That’s who he was."

Coach Jackson attested to that statement as well.

"All of the guys loved him," Jackson said. "I don’t think there was ever an issue on the team where Chris was brought into it."

Living the American dream, treated everyone like family and Chris never got involved in a negative issue.

That all changed May 8, 2022.

Starting the journey

Chris' parents, Augustine and Annie, originally hailed from Liberia.

In December of 1989, a man named Charles Taylor left the Ivory Coast and entered Liberia with the intent of leading a rebellion to topple the government of President Samuel Doe. That marked the beginning of the first Liberian Civil War.

Augustine and Annie, along with roughly 1 million others, eventually fled the country. They sought safe haven in the neighboring Ivory Coast; coincidentally, the country that Taylor came from. They settled in a refugee camp known as Peace Town in the village of Nicla, just outside the city of Guiglo.

According to Abou Bamba, an associate professor of African studies at Gettysburg College, Peace Town housed roughly 7,000 Liberian refugees in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Chris was born there in 1997.

Though the Doerue family was free from one conflict, it was out of the frying pan and into the fire. Tension was brewing in the Ivory Coast following roughly three decades of relative stability.

Following the death of longtime president Félix Houphouët-Boigny, Henri Konan Bédié was elected to take his place in 1993. It was during this time of tension and economic crisis that Bédié coined the term Ivoirité.

"It was designed to instill a sense of belonging among all of the Ivorians regardless of religion or region," Bamba said. "In practice, it ended up creating a sense of exclusion toward people from the north."

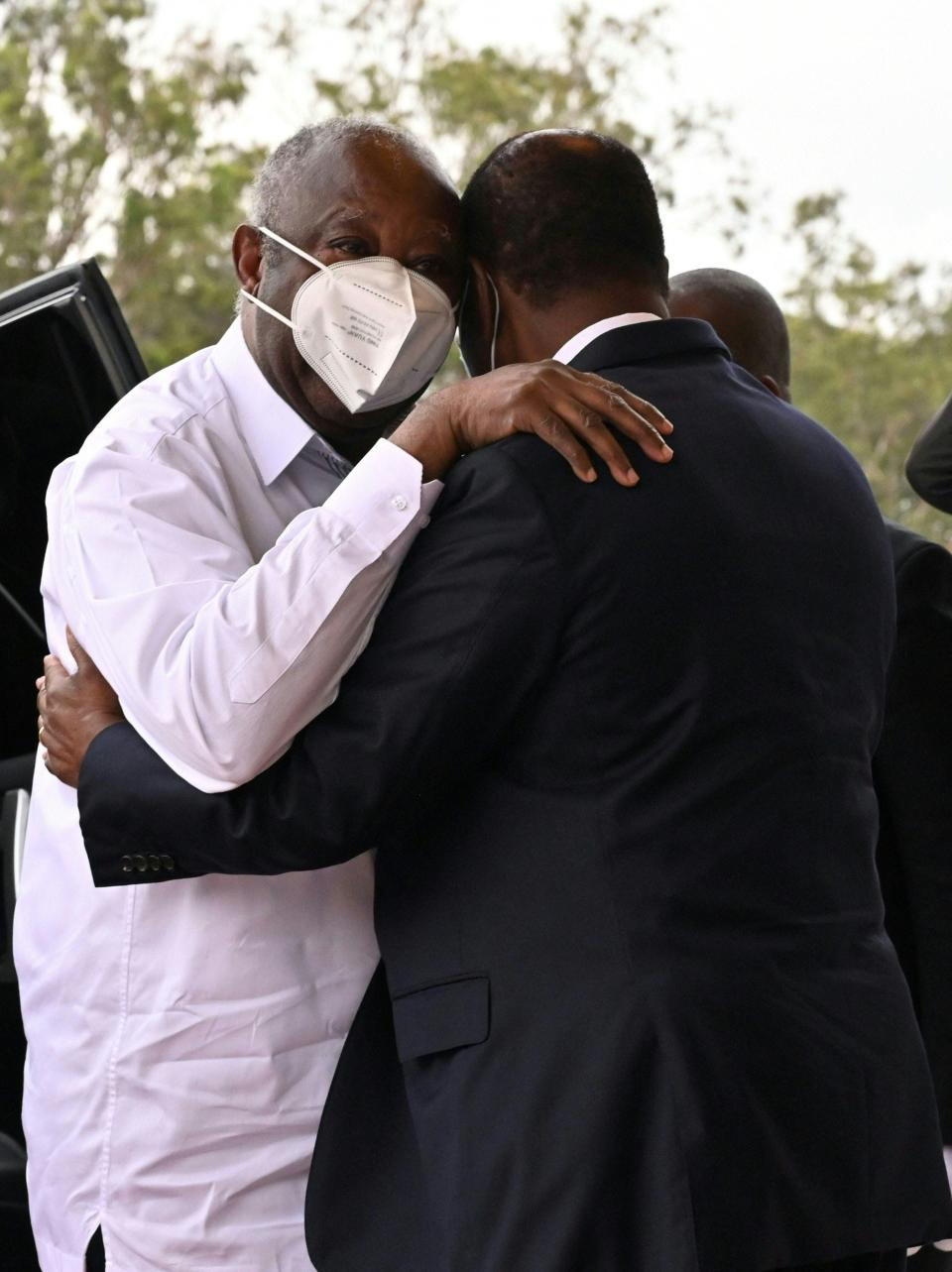

Bédié was removed from power following a coup in 1999. The military took over and expanded the Ivoirité concept before allowing elections to be conducted in 2000. Alassane Ouatarra and Laurent Gbagbo were expected to contend for president.

However, a law based in Ivoirité was passed requiring that both parents of a candidate be born within the Ivory Coast. This excluded Ouatarra from running.

Gbagbo was elected and Ouatarra's supporters took to the streets demanding free and fair elections. Tension continued to brew over the next two years, culminating in rebels, mostly loyal to Ouatarra, staging an attempted coup. This split the predominantly Muslim, pro-Ouatarra north and the mostly Christian, pro-Gbagbo south.

The conflict reached across the Ivory Coast with various other rebel factions forming. Some groups even took to recruiting Liberian refugees. With the conflict raging and uncertainty rising, many people who fled to the Ivory Coast to escape one conflict found themselves seeking refuge once again.

Including the Doerues.

Arriving in America

Junior Doerue described learning that his family would be moving to the U.S. as "winning the lottery." He was 11 then and may not have realized he was actually right.

“A lottery system was created by the U.S. government to allow immigrants to the United States from countries that don’t have a substantial number of immigrants already in the United States," Bamba said. "You need to be at least high school educated, make an application online, and if you are chosen then you are allowed to immigrate and become green card holder in the U.S.”

Junior said getting selected was a wonderful yet bittersweet experience.

"We were all happy, but it was kind of a sweet and sad moment," he said. "We were leaving what we knew as home, but we were happy to go because of what was going on in the country.”

The plan was for the Doerues to immigrate to Utah, but the children had an aunt already living in Amarillo. To ease the transition, the family wound up in the Texas Panhandle.

It was almost destined that from there the children would become embedded into the storied athletic culture of Amarillo.

"My dad used to play soccer back in his day," Junior said. "My mom played soccer back in her day too. In Africa, that’s the main sport, so there’s athletics in our genes."

Junior participated in track in college. One of the younger brothers, King Doerue, is the starting running back for Purdue. For Chris, it was always basketball that drew him in.

Chris started playing at Sam Houston Junior High before winding up at Tascosa for high school. After playing his freshman year, fluid began building up in his knee resulting in cartilage damage. As a stipulation for his recovery, he would have to miss his sophomore year.

“When he got injured, he was devastated," Junior said. "He cried for a little bit and said, 'Man, I just want to play basketball. ... ' I remember one day I bought a knee brace and I was like, ‘Bro, quit crying.’ Put the knee brace on and go do what you love and he said, 'OK.' "

Though surgery was recommended, Junior said his family couldn't afford it. Chris instead had to take the long path to recovery. That's when his work ethic and love for the game began to show.

"He had to sit out his sophomore year, so he became our manager," Jackson said. "He said, ‘I’ll do whatever I’ve got to do to just stay around.’ He came back as a junior and even then they had him on restrictions. He said, ‘Coach, I just want to play. I’ll overcome whatever it is they’re telling me I’ve got to do’ and he did."

Jackson described Chris as a "lead by example" type of player. He was quiet, but did whatever was asked of him. In a day and age when so many kids want to score, Jackson said it was his defense that Chris prided himself on.

"Anytime we went to the Metroplex, he wanted to be on the other team’s best player," Jackson said. "He was our defensive stopper. He took that personally and he took it to heart and he really excelled at that role for us. ... He guarded guys like Jarrett Culver."

As in the same Jarrett Culver that led Texas Tech to the championship game of the 2019 NCAA Tournament before going No. 6 overall in the NBA Draft. The 6-foot-6 guard from Lubbock Coronado now plays for the Memphis Grizzlies.

Tascosa had one of the best seasons in school history Chris' senior year. The Rebels finished 31-1, winning district and area championships in Class 6A before falling in the regional quarterfinals to Arlington Martin. Jackson said having Chris on the floor played a big role in the Rebels' success.

In turn, Chris earned an opportunity to continue his athletic and academic career with a scholarship to Wayland Baptist.

“He worked himself into that opportunity at Wayland," Jackson said. "Wayland came in and watched us practice and really liked him. ... I think what appealed to Wayland about him was his character and his willingness to do whatever needed to be done.”

That seemed to remain true even after things began to change for Chris.

I'm still here

Chris played two years for Wayland and earned an associate's degree in criminal justice. From there, things become a little unclear.

Junior said Chris transferred to a community college somewhere near Dallas where he continued to play basketball. Neither Junior nor Jackson could explain exactly what happened after that, but at some point in his fourth year, Chris made a decision.

“His senior year, he came home and said, ‘Hey man, I’m done with sports,’ " Junior said. "He just got tired of it. He said he played his fair share and did the best he could, so he was done with sports. ... He was going to take a year off and then go get his bachelor's. I never heard about him going back to school after he took that year off.”

From there, Chris began working at Tyson until the COVID-19 pandemic started. Junior said Chris spent time traveling and "being young" during this period.

His playing days were over, but basketball was still a significant part of his life .

Junior said Chris spent a lot of time training first- and second-graders how to play basketball. He was deeply involved with Junior's children along with his other nieces and nephews. He could often be seen around the gym at Tascosa High School, training kids and connecting with old friends.

“He’d still come back and play with our guys sometimes," Jackson said. "Anytime we had a kid sign with someone, he’d come up and see it. Those guys (on the 2015-16 team) were all close, and they kept in touch with the program and the guys who were still playing."

Chris was in attendance this past April when Ashraf Barsham signed his letter of intent to play for Clarendon College. Jackson spoke with him then, reminiscing over old times and exchanging pleasantries.

Jackson didn't know it then, but that was the last time he'd ever see Chris Doerue.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This is the first in a four-part series on the life and death of former Tascosa standout Chris Doerue.

This article originally appeared on Amarillo Globe-News: Former basketball star Chris Doerue: From the Ivory Coast to Amarillo