An Ivy League son and his undocumented mother share the same dream of America | Opinion

In 1998, Momma already knew what outfit she would wear when she saw her parents again: an emerald skirt with flower prints, beige flats and the jade bracelet she received as a childhood gift from her father. Some afternoons, when she thinks no one else is watching, she removes the outfit from a box and puts it on before the mirror in our one-bedroom apartment.

Momma is a planner, and I’ve always admired that about her. But a part of me also knows that fashion is maybe the most certain thing in her life. This past April marked the 25th anniversary of her leaving a small village in China for a future in the U.S.; her 25th year as an undocumented immigrant breathing on American soil. One of the conditions of that existence, of course, is that she cannot hold a U.S. passport or take a plane without risking deportation.

We celebrated Momma’s birthday in Washington D.C. last month. She doesn’t turn 50 until December, but by then, I will be back in college for my junior year — a three-hour Amtrak ride from our home in New York. This summer felt like the perfect opportunity: I was ending an internship near Capitol Hill and I had scraped enough money together for a hotel for the both of us. But the real reason I was grateful for the timing? She could help me with my suitcases going back home.

Opinion

We saw the Library of Congress and bought an overpriced pineapple sundae from the ice cream truck near the Washington Monument. Momma snapped way too many photos — as an Asian mother would — and asked lots of questions about the architecture, which I pretended to have the answers to.

By night’s end, the two of us were sitting by the edge of the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool, watching a duckling struggle to stay awake next to its mother. It was humid and quiet. I thought about jumping into the cold water and wanted to suggest it out loud as a joke, but then I stopped. It’s unsettling to think that just the thoughts — the dumbest ones, too — were a privilege I owned: As an American citizen; as a college student; as a man.

Momma, sitting next to me and leaning on my shoulder, was wearing her signature black blazer. I wondered if she was thinking about her own parents, whom she has now spent more time calling on the phone than physically being with. Momma never looked more beautiful and more capable that night by the reflecting pool, but she is never safe. She is always hiding. She is always formally dressed for the occasion.

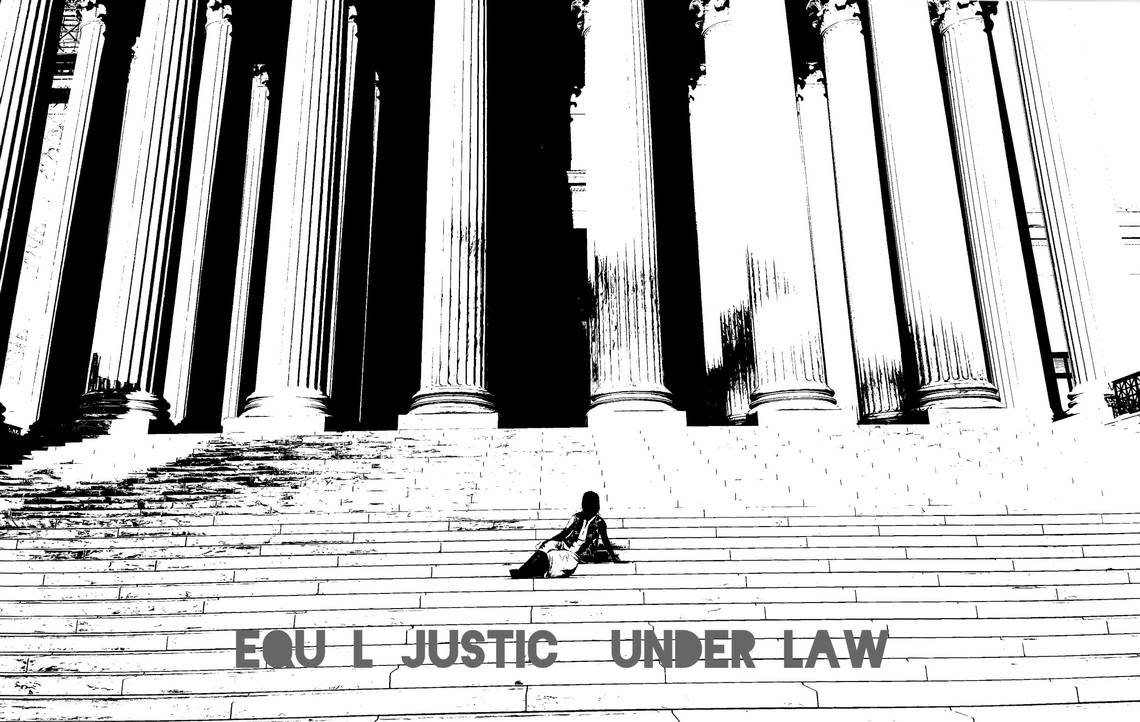

There is something fundamentally wrong to me about gracing the historied locations of this nation, knowing that my parent remains seated in the periphery of that nation’s vision. There is something uncomfortable about climbing ivory towers of an Ivy league college campus, relishing a complicated view of the city below that she will never be allowed to see.

I’ve always told Momma that in another life, as teenagers, we would have made perfect best friends.

These past few months, as I drank matcha lattes, posted sunkissed photos of myself on Instagram and built houses made out of poker cards with other Hill interns on the steps of the Supreme Court, I wished she could have been there, to see those houses crumble.

I have all these dreams of changing the world and going to work in cities from Sacramento to Chicago. I lie to Momma, telling her that I’ll always bring her along. When you love somebody, you want to be perfect for them. You make promises you don’t have the power to keep. For Momma, that means practicing an outfit in front of a mirror.

Today, as neighborhoods from mine in Brooklyn to yours in Sacramento continue to support an influx of asylum-seeking migrants, I ask you not to forget about the immigrants who came before — the honest, longtime pillars of our American democracy and economy.

This is not an attempt to pit two vulnerable groups against each other, nor is this an argument for whether unlawful entry to America should be deemed a mistake. This is simply a reminder that the undocumented immigrants of Momma’s generation — those who arrived in the great wave of the ’90s — will not be here forever, and neither will their parents, many of whom have either already passed away or remain in their home countries.

Democrats have been too ambitious on immigration

Democrats are too often so forward and ambitious with their immigration proposals that they forget about the opportunity to make a real human compromise. Conservatives have already shown that they are against the idea of material amnesty, even if offered the prospect of tightened border control and having the undocumented pay a fine.

It is time to redirect our current priorities away from forgiveness and toward a recognition of our common humanity.

For two decades, no matter what political makeup constituted the executive and legislative bodies, the federal government has stagnated on passing comprehensive immigration reform, with most changes being small provisions and funding bills. It is time to stop believing that showering relief money onto the impoverished without examination of policies at large will solve immigrants’ biggest problems. It is time to stop with the backseat excuses.

There are multiple layers to American citizenship: the right to vote, Social Security benefits and the ability to travel to and from the U.S. Let’s start with the third. The very least that aging immigrants like Momma deserve is the opportunity to reunite with their elderly parents without fear of being unable to come back or losing the family they have built here. I cannot think of a crueler punishment than to ask a person to choose between two homes, two cuts of their own flesh. Whether Momma deserves future employment and social privileges in America is not up to me to decide, but I can confidently say that those are not her most immediate needs.

Let’s remind President Joe Biden what is missing from the American Families Plan, and consider a few amendments if the latest immigration bills, such as the Citizenship for Essential Workers Act, are defeated. If we are against the idea of giving the undocumented wings for permanent flight, let’s lend them ours so they can visit their family, particularly those who have been at the front line of the American fiscal climb for decades. FaceTime and phone calls are not enough to see what time, and a pandemic, has done to their loved ones, oceans away.

Sometimes, I imagine my 49-year-old, Taylor Swift-loving, sometimes cranky, always caring, excellent planner of a mother as a 24-year-old. I am just four years younger than she was then, but she is braver, stronger and more committed to serving our country than I have ever been. I imagine her and Grandma standing beside each other for the last time on the edge of their family farm.

Momma arrived in America with only the essentials in her bag, her braids conditioned with lard, the clothes on her back, a jade bracelet clasped around the wrist and a few stories to share with her future children. I imagine her memories flip before her like a sped-up picture book — sitting on her father’s old motorcycle, arms spread like wings; taking the train with her sister to the Guangzhou night market to try barbecued fish balls. Momma looks at the dirt road ahead — a blank space and a tunnel into a life outside of the impoverished village — and then back at Grandma.

“啊妈, 同一时间,一百年之后,” she jokes. “The same time, Mom, one hundred years from now.”