J. Dennis Robinson: When your dad turns 100

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 1923, as the Seacoast was celebrating its 300th anniversary, my father was busy being born. One hundred years later, now living in Durham, New Hampshire, he's about to celebrate what I call his "first centennial."

In the interim, John Brewster Robinson fought in World War II, was married for 70-plus years, raised three sons, built hundreds of model airplanes, and worked a full career for AT&T. He’s been retired, he proudly points out, longer than he held a job.

These days my father resides at Brookdale/Sprucewood in Durham, where he is busy making paper sculptures, studying quantum physics, and sticking to a strict keto diet. On Thursdays, he likes to catch a ride to Market Basket in Lee, where the cashiers know him by name.

I met my father in 1951. We were living back then with my mother, Phyllis, in a second-floor apartment in Southbridge, Massachusetts. Dad was a telephone installer. I was a baby. Neither of us guessed he was on his way to becoming a centenarian. But here we are, planning the details of an event he calls "no big deal." And yet, it is.

Playing the long game

You read about famous people who reach this milestone — Bob Hope, George Burns, Kirk Douglas, Grandma Moses, Methuselah. But you never think you’ll have one on speed-dial or share his DNA.

I was in grammar school watching a parade when the mathematics of life first hit me. A sign on one of the antique cars in the parade read “Last Veteran of the Civil War.” I caught the eye of the old man in the vintage car. That memory is seared into my brain, but, according to Wikipedia, it probably never happened.

There are 97,000 centenarians in the United States today (Wikipedia again) and close to 600,000 worldwide. Eighty-five percent are women. Statistically my father had a 1% chance of hitting the mark. My odds are 8.2%. A child born today has a 28% chance of reaching 100, and a 1-in-10 chance of living to 106.

We are currently celebrating New Hampshire’s 400th anniversary. That’s nuts, of course, since indigenous people have been here for at least 12,000 years. But we celebrate all the same. And that got me thinking. If someone born in 1623 lived 100 years, and someone born in 1723 did the same — imagine that! New Hampshire is only as old as FOUR centenarians linked end-to-end.

War stories

Typical of his generation, Dad never said much about the war when we were kids. By the Sixties, when I was in a rock band and growing my hair, talk of politics and religion were also off the table. The war stories came much later when my late brother Brian, an archaeologist, began digging up the facts.

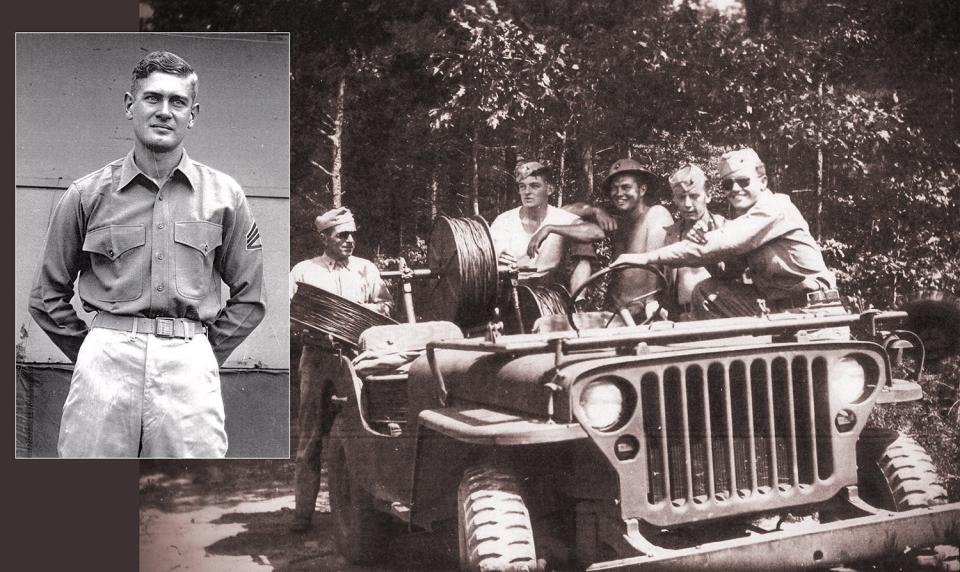

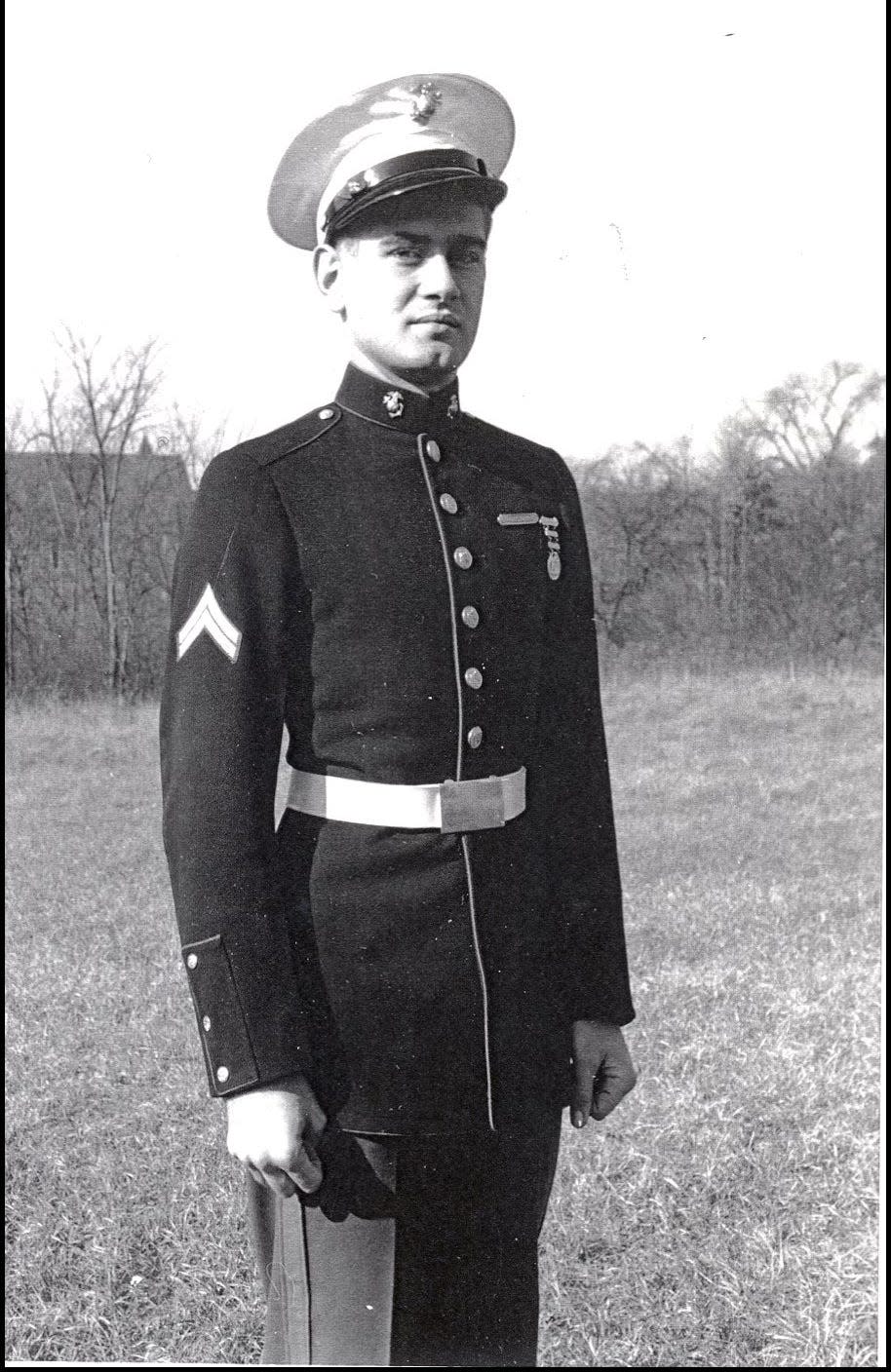

John Robinson, we learned, had been working as a stock clerk at a hat factory in Upton, Massachusetts, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941. Exactly one year later he entered boot camp at Parris Island, South Carolina. Following intense training in Washington D.C. and Norfolk, Virgnia, he joined a secret operation. The “Beach Jumpers,” originated by actor Lt. Douglas E. Fairbanks Jr., were highly trained electrical experts. They used special equipment to distract the enemy from spotting U.S. troops landing on foreign soil.

“We were told it was not exactly a suicide mission,” dad recalls. After recording the live sounds of tanks, trucks and troops onto wire recorders, the Jumpers used hidden powerful speakers to simulate the sounds of a mock landing. The 1940s technology did not live up to the concept and the U.S. Marine version of the project was scrapped.

Reassigned to the base at Quantico, Virginia, he joined a newly formed “Sound Ranging Squad.” While fighting in the Pacific, Marines were being harassed by hidden Japanese guns that could appear suddenly, fire and disappear undetected. The physics department at Duke University had developed a sound ranging device, nicknamed DODAR, that was portable enough to be used in the field to detect hidden artillery by sound. Japanese gunners, it was later discovered, could swing their guns out on tracks, fire and disappear into camouflaged sites before the shells landed.

Sgt. John Robinson’s experimental Sound Ranging Unit arrived at the volcanic island of Iwo Jima on Feb. 19, 1945. “We kept our heads down and heard shells landing close by in the water,” dad recalls. Landing vehicles got stuck in the volcanic ash and getting the sensitive sound equipment ashore and into foxholes was hair-raising. How the team used microphones and sound to target enemy guns is a complex story, but the DODAR system worked and the enemy gun was neutralized.

Filling in the gaps

I call a couple of times a week and my brother Jeff checks in with dad from South Carolina on his Echo Show. Today we rarely reminisce. My father reads the MIT Quarterly and keeps up to the minute on news and weather. We talk mostly about what’s for dinner, what I’m writing, and what he’s reading. But occasionally a chunk of the past slips in.

There was that time, I learned recently, when my father’s father, Jake Robinson, tried to teach his young son to catch mink. Grandpa, you see, was a fur trapper. My father didn’t take to caging little animals, smacking them on the head and skinning them. During his only foray into the wild, he recalls, one of the supposedly dead mammals jumped out of Grampa Jake’s overcoat and made a failed run for freedom. By the time I knew my grandfather, he was planting corn, sharpening saws, building fine furniture, and raising giant worms in huge tanks under the barn.

Centennials make you think. I’ve written over 3,000 articles about other people’s history, but rarely tap my family tree. Preparing my father’s April 30 birthday bash meant reaching out to people I haven’t seen in decades. We are, it appears, a hard-working bunch. The relatives include teachers, bookkeepers, EMTs, nurses and factory workers. My great-grandfather ran a dairy farm and his descendants still do. My relatives include a fire chief, a surveyor, a chauffeur, store owners and factory workers galore, a naval officer, hairdresser, chef, videographer, carpenter, economist, lawyer, photographer, and more. No millionaires. No movie stars or presidents. Just us folks.

Doing the math

While my father built ornate wooden model airplanes in the basement, I built plastic monsters. When I was in fifth grade, we collaborated on a portable computer. This was the early Sixties. Built in a cigar box, the device had two wooden dials that turned on ten brass fasteners labeled from zero to nine. Inside was a nest of colorful wires that we connected with a soldering iron.

The computer could only do one thing — convert decimal numbers (Base 10) to binary (Base 2). If you set the dials on a two-digit number, a row of lights would indicate the translation. A light on indicated a “1” and a light off was a “0.” Turn the dials to 25, for example and you got 11001. It’s pretty much how everything works these days.

I entered our computer into the science fair at the McKelvie School gym in Bedford and won first prize. It was a watershed moment. I learned that I hated math.

Because our primitive laptop had only two dials, the biggest number we could convert was 99. I mentioned this to my father recently. He’s a numbers man. I'm a word guy.

“You know,” I said. “You are about to re-enter the digital age.” The decimal number 100, in binary, equals four. Next year, at 101, he will be five. At 72, my digital age is 1001000. No wonder I feel old while my father is so spry.

As a telephone installer and later a company leader, my father watched computers shrink from room-sized monsters into the palm of his hand. He’s seen battery-powered Model Ts become battery-powered modern trucks. But let’s not get too nostalgic. He’s only 100. Who knows what miracles he has yet to see.

More on John Robinson: Wentworth-Douglass Hospital honors cancer patient who is turning 100

J. Dennis Robinson, all rights reserved. Robinson will release three new books in 2023, including a hardcover history of New Castle, New Hampshire and a study of New Hampshire’s first English settlers in 1623. "Portsmouth Time Machine," a 400-year history of the city for kids, illustrated by Robert Squier, is due out soon. For information, visit jdennisrobinson.com.

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: J. Dennis Robinson: When your dad turns 100