Jacksonville University's new law school fills void another way after Florida Coastal closing

A year after Jacksonville’s only law school closed, another has opened to a warm reception.

But Jacksonville University’s new College of Law, in downtown office space a few blocks from the city’s courts, is promising to be something different from the for-profit Florida Coastal School of Law, which shut down after being cut off from federal student loans.

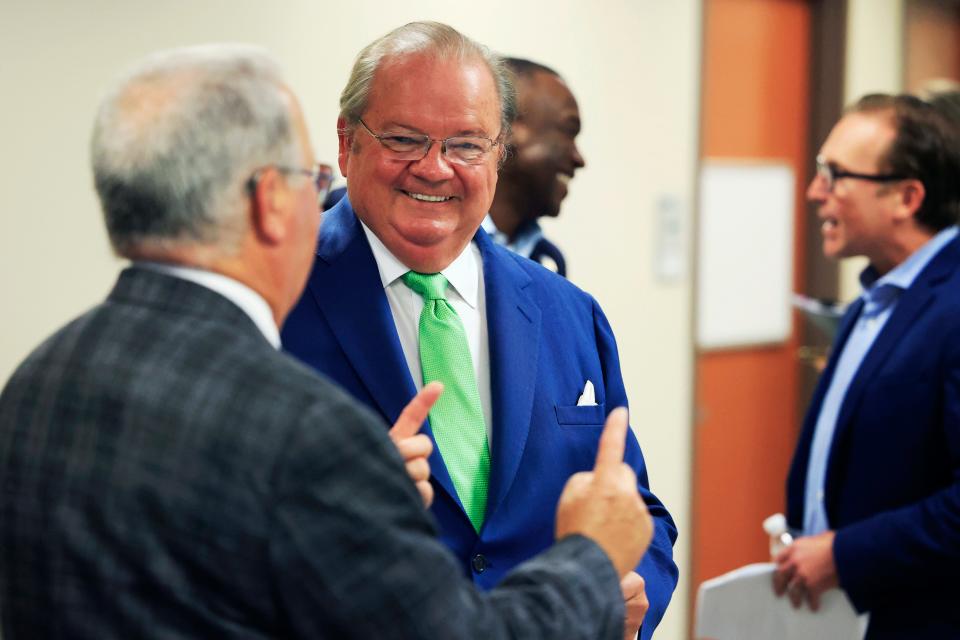

“We’re not focused on making the most profit,” Dean Nicholas W. Allard said. “We’re focused on taking that investment … and returning it with interest.”

The returns supporters are expecting can be measured beyond balance sheets.

“This is a real talent need in Jacksonville,” said Mayor Lenny Curry, whose administration has helped underwrite some of JU’s expenses.

No other Florida city Jacksonville’s size is without a law school, and attorneys say that gap can affect fields ranging from the price of attorneys to people’s ability to get help when they can’t pay for it.

The school “is going to feed young lawyers into the market,” said James Poindexter, president of the young lawyers section of the Jacksonville Bar Association.

Poindexter said he’s regularly contacted by law firms having trouble finding young help.

“That just wasn’t the case when Florida Coastal was pumping out lawyers in the hundreds every year,” he said.

That doesn’t mean JU should mass-produce lawyers, however.

“Focusing on quantity, you lose the quality,” said Poindexter, himself a 2014 Florida Coastal graduate who recalled hundreds of students grouped into a string of 50-person sections in his first year.

JU only has 14 law students in its first semester, which began early last month.

The school is expecting to add some — maybe 20 or 30 more –— when a new semester starts in January, and applications are being accepted now. The school’s website, ju.edu/law, invites people to register for information sessions.

Scholarships available to bring down JU tuitions

The new college’s tuition is $36,000 per year, with scholarships that reduce the cost to $21,600. “We are working every day to bring it down even further with scholarships through private fundraising effort,” a JU spokeswoman said.

Students will be entering a school that isn’t accredited by the American Bar Association, but JU reminds website visitors that it has received accreditation for more than 30 programs in the past decade, in fields from healthcare to business administration.

JU is careful to guard its reputation and will work deliberately through the steps to become accredited, said Allard, a Yale Law School graduate who was previously dean and president of Brooklyn Law School , a 121-year-old private college in New York.

“We are going to color within the lines,” he said of accreditation, which is designed to take at least three years. Provisional approval by the ABA is possible after a law school has operated for a year.

JU seeking to set itself apart from for-profit Florida Coastal School of Law

The connection to a well-established university is part of the new law school’s difference from Florida Coastal, which employed some of JU's law school staff but was owned by a firm that exclusively operated, and eventually closed, law schools in three states.

Allard said he’s been connecting with key people in JU’s other colleges about ways that knowledge developed there can be applied to teaching law.

One example could be virtual reality, which business school students use to practice big interviews and nursing students use to train in surgical procedures without the need for human bodies.

The same technology can give law students the potential to simulate taking depositions, questioning witnesses and arguing cases to avatars of the U.S. Supreme Court, Allard said.

By the same token, law school faculty have knowledge that can connect with the research of JU’s other colleges. Allard pointed to Nathan Richardson, a law professor with a deep background in climate change and environmental regulation whose work overlaps with work in JU’s Marine Science Research Institute. Other faculty can connect with the Brooks Rehabilitation College of Healthcare Sciences for work on subjects ranging from HIPPA to mental health fiduciary duties.

“We’re going to be giving a lot and we’ll be getting a lot” from being part of JU, Allard said.

That’s not too different from how lawyers talk about having a law school in town again.

“Jacksonville really needs a law school,” said Michael Freed, a JU graduate who was one of the law school’s early champions. Noted for running back-to-back marathons to raise money for Jacksonville Area Legal Aid, Freed said local law students can become valuable sources of labor to help people who can’t afford a lawyer work through their legal problems.

At the same time, Freed said his firm, Gunster, is hoping to find able young talent it can eventually hire for itself.

Being local helps talent grow where it is, said Timothy Miller, a 2012 Florida Coastal graduate who during his third year at law school spent several days a week interning at the State Attorney’s Office in Jacksonville. After passing the Bar the internship led to a job as a prosecutor where he worked opposite the defense lawyers he works with now as an attorney at the San Marco firm of Harris Guidi Rosner P.A.

A Jacksonville native, Miller knew he wanted to practice law here, but being able to study law here and see it applied made that hope real.

Having JU’s law instruction downtown is being praised as helping students get connected to courtrooms and the city’s major law firms.

U.S. District Court Chief Judge Timothy Corrigan said he expects to deliver some talks at the law school, and Allard told people at a formal ribbon-cutting Thursday that people in both the state and federal courthouses have spotted students and alerted them to hearings that could be instructive.

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: JU debuts new law school in contrast to Jacksonville's Florida Coastal