In Jacob Studer, Columbus had enthusiastic pitchman promoting city in 1870s

In 1872, Columbus was a rapidly growing city.

A town of about 18,000 people in 1860, Columbus was an admixture of original residents and recent Irish and German immigrants. By 1870, Columbus was a city of more than 31,000 people and was spreading in commerce and housing in all directions.

There were many reasons for this rapid expansion of the capital city. Eight railroads entered Columbus, and the town had become a rail hub during the Civil War. A number of new businesses took advantage of cheap supplies and a ready labor force. Among the most important of these businesses were buggy companies.

The Columbus Buggy Company opened in 1855 as the Iron Buggy Company. That company had problems with customers complaining that the ride in iron seats was rough, and who really wanted a buggy that rusted? So the company changed strategies, became Columbus Buggy and soon was successful making buggies of all sorts.

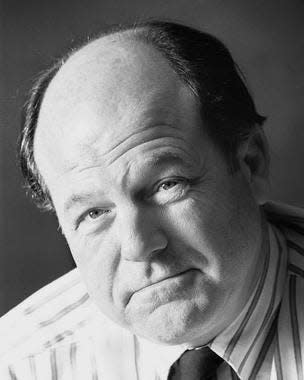

Columbus had a lot of enthusiastic sponsors, marketers and promoters in the years after the Civil War. But by 1872, the man most vigorously active promoting the city as a place to work, live and visit was Jacob Studer. Born in 1840 in Columbus to German immigrants living in “die alte sud ende” or the Old South End, Studer attended local schools and apprenticed himself as a “printer’s devil” to learn the printing trade. Studer also spent his spare time as a skilled sketch artist.

By the end of the Civil War, Studer became convinced that the growing capital city needed a promoter. So Studer became a regular speaker, writer and advocate for Columbus. He visited many neighborhoods, met the people and learned their stories. He took the information he had learned and wrote a book called "Columbus, Ohio – Its History, Resources and Progress." Published in 1873, was the first general history of the Columbus area to be printed since William T. Martin's "History of Franklin County" in 1858.

Unlike histories to come which would cite sources and try to remain objective in outlook, Studer’s history – while telling a good story – is unabashedly proud to promote Columbus. His story is mostly accurate, most of the time. But mixed with state, local and personal history is a solid dose of positive marketing of the city.

“Columbus is pleasantly situated on each side of the Scioto River, but principally on the eastern side. … It is laid out in a rectangular plan. In its public and private edifices, in the improvement of its streets and parks, and in its general appearance, there is a skillful blending of beauty with utility, and of uniformity with variety.

“Not very many years ago, it was a common saying that Columbus owed its existence and all its importance to the State capital and the state institutions located within its limits. But its progress of late years has proved the falsity of such assertions and silenced the tongue of slander.”

Studer’s book continues in this vein, exploring and explaining the economic, social and cultural aspects of the city. He steers clear of politics for the most part, explaining the roles of police, fire and public service offices but saying little about the people who filled them. This is wise, from a marketing perspective, if one is trying to sell books to all sorts of people.

With his book well underway, Studer set out to market the city in a more organized way. In November 1872, he wrote a letter to the editors of local newspapers: “Many of our citizens have signed a call for a public meeting at the Board of Trade Room in the City Hall building for the purpose of organizing an association such as was contemplated in the construction of that apartment.”

This was the new City Hall on State Street across from the capital and would be a presence near the Statehouse until it burned in 1921. The Ohio Theatre occupies that ground today.

Studer persuaded, cajoled and promoted a Board of Trade for Columbus until it actually came into being in 1873 with a board, paid members and regular meetings. But the enthusiasm lasted only briefly. By 1874, the group was dormant and it would not be until 1885 that a permanent Board of Trade – now our Chamber of Commerce – was founded.

By that time, Studer had moved on to New York. In that city he compiled and edited for publication his "Studer’s Popular Ornithology," which featured color portraits of birds by artist Theodore Jasper.

Studer had outlived his wife and most of his children when he died asleep at age 64 at his desk in his New York apartment in August 1904. He still was working to promote causes and places he believed in.

And one of those places he believed in most was Columbus. His "History of Columbus" remains in print.

Local historian and author Ed Lentz writes the As It Were column for ThisWeek Community News and The Columbus Dispatch.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Jacob Studer unabashedly promoted Columbus 150 years ago