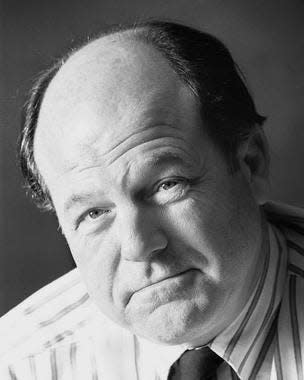

James B. Gardiner was a journalist, joker, tavern owner in Columbus

There is an old saying, “Every decent deck of cards needs a joker.”

One might add that a community might need one, too. If that is the case, James B. Gardiner did his best to fill that role.

Many of the people who settled in central Ohio in the early years after the American Revolution were not of a frivolous mind. The Ohio country north and west of the Ohio River was opened for settlement, with land grants for veterans and sale at low pieces to garner income to various public and private landowners.

People like frontier surveyor Lucas Sullivant, who laid out the village of Franklinton at the forks of the Scioto River in 1797, were serious people indeed.

But the new people came to stay. They built new homes and new shops and stores, and their blazed trails became the streets of the new towns. The new people succeeded as they helped one another in times of need and brought their ideas of proper religion, education and culture with them to their new homes. They were generally very serious about their intentions to stay and build a new society in the new land.

And then came people like James B. Gardiner.

Lentz column:The last Wyandot was one of the most memorable

In addition to the people who had found the town and country of their liking and were determined to stay, there were always restless residents, as well. Some of these people were not all that friendly and law-abiding. But many, if not most of them, meant well. They just had a bit of trouble finding their place. James Gardiner was a good case in point.

Born in Maryland in 1789, the year George Washington became the first president, Gardiner arrived in Marietta with his family and was apprenticed as a printer’s “devil,” or errand boy, when he was quite young. He grew up learning the printing trade but was anxious to make his own way in the world. In 1810, reaching the age of 21, he moved with his wife Mary to the town of Franklinton.

It was a bold move. The Treaty of Greenville of 1795 had set aside the northern third of what is now Ohio to Native Americans. That land was only a few miles from Franklinton, and that new town was the most northern settlement in central Ohio. It would have been threatened had a war begun. And in June 1812, a war began.

Gardiner brought a rather elderly press to the new community and opened the first newspaper in Greater Columbus. He called it the Freeman’s Chronicle and proclaimed his viewpoint on the first page of the first issue:

"Here shall the press the people’s rights maintain; Unawed by influence, unbribed by gain,

"Here patriot truth its glorious precepts draw; Pledged to religion, liberty and law."

The Chronicle was a regular publication during the War of 1812, and much of what we know about frontier Franklinton – a town where many people had never learned to read – comes from its pages. An early history records what happened next.

"He was a man of ideas, strong in his convictions, and always ready to contend for what he believed to be right. The Chronicle was a very creditable paper for its opportunities, but was not financially successful, and Mr. Gardiner abandoned it with the intention to never to enter the journalistic profession again.”

Instead, with a wife and several children to support, he went into a new and different business. It was later observed that many, if not most, of the early buildings in frontier towns were taverns. Perhaps noting this, Gardiner became a tavern owner and soon was dabbling in other businesses.

He had adopted the nom de plume of “Cokeley” while in the newspaper business and kept that name as a satirist and practical joker in the new town of Columbus. It is now recorded as to how well his jokes were accepted by the stoic residents of the city, but no harm was meant so his wit was tolerated.

But in time, he became convinced that his future lay elsewhere. He returned to journalism and, as a later account noted, was “driven to it by his inclination, and as he frankly said to the public, by the necessity of earning a livelihood.” In 1826, he began the publication in Xenia of the People’s Press.

While publishing the paper, he served a term in the Ohio Senate in 1826 and became something of an advocate of the policies of Andrew Jackson. During President Jackson’s administration, he served as an Indian agent and assisted in removing the Indian tribes from Ohio.

He later returned to Columbus, disenchanted with Jackson, and with a partner opened an Ohio People’s Press dedicated to the policies of William Henry Harrison. On April 14, 1837, his rather exuberant lifestyle came to an end. Attending a land sale in Marion, he experienced a stroke and died. James B. Gardiner is buried in Green Lawn Cemetery in Columbus.

Local historian and author Ed Lentz writes the As It Were column for ThisWeek Community News and The Columbus Dispatch.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: James B. Gardiner — Columbus journalist, joker, tavern owner