James Webb Space Telescope reveals rich chemistry of planet-forming disks for the 1st time

For the first time since its launch, NASA's largest and most powerful space observatory has eyed the chemistry in the dusty disks around distant young stars, giving astronomers a peek at the birthplaces of exoplanets.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST or Webb) has unveiled an assortment of chemical compounds embedded in the disks of gas and dust surrounding three low-mass stars that are about five to 10 times less massive than the sun. The "chemically diverse" compounds that Webb spotted include organic molecules like carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, acetylene and first detections of benzene, as well as the life-friendly water. The stars studied by Webb are only a few million years old, which means the chemicals spotted by the telescope will ultimately be inherited by planets and their atmospheres that will form in these cosmic nurseries, astronomers say.

Webb's data "allows us to determine physical conditions like densities and temperatures across and inside those planet-forming disks, directly where the planets grow," Thomas Henning, a director at the Max Planck Institute of Astronomy in Germany, said in a statement published April 13.

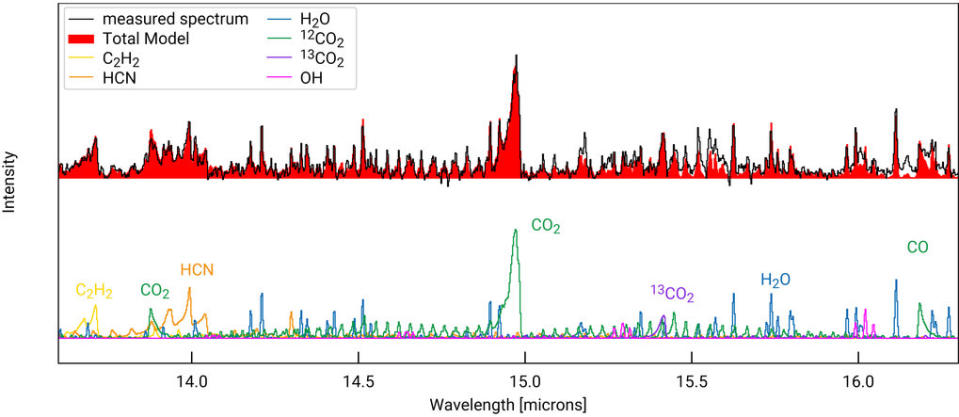

Henning is an author on two of the recent three studies that highlight findings from data collected by the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) onboard Webb, which is a hybrid tool that clicks images as well as collects light spectra from deep sky objects. Various molecules absorb light at different wavelengths, which astronomers can detect in the spectra as unique chemical fingerprints of the studied objects.

Long-lost crystals rediscovered

One of Webb's targets was EX Lup, a star in the Lupus cloud over 500 light-years away from Earth. Since the star’s first detectable eruption in 1901, it has flared up seven times in the past. According to the researchers, these irregular events likely played a role in hosting "embryos of comets and planets" that they think are present in the star’s disk.

EX Lup last erupted in 2008, which was also its most powerful outburst, during which it heated the surrounding ring of gas and dust. This in turn triggered the formation of intriguing crystalline silicates — specifically forsterite or white olivine — within 93 million miles (150 million km), or the distance between the sun and Earth.

"However, for the past 15 years, astronomers did not have an instrument sensitive enough to detect the tenuous signal of the slowly cooling crystals," according to a statement published in March.

When astronomers finally studied EX Lup once again in 2022 using Webb, they rediscovered the silicate crystals, but in those 15 years the crystals had flowed outward to about 279 million miles (450 million km) or three times the distance between the sun and Earth, according to the latest study.

So the crystals are now close to the star's snow line — the point in its system where temperatures are cool enough for ice and snow to first form. Astronomers say these frozen compounds will likely be embedded in newborn planets and comets.

The team also detected "a forest of emission lines" in the star's spectra corresponding to carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and clear signals of water, according to the study.

A dry disk of gas and dust with a rare type of carbon dioxide

In August 2022, Webb imaged a distant star GW Lup in a cluster of stars and gas called Lupus 1. Astronomers studying the star's spectra found that the disk around it is warm but dry, which means it displays very weak water signals.

"While we clearly detected molecules containing carbon and oxygen, there is much less water present than expected," Sierra Grant, a postdoc at the Max Planck Institute for extraterrestrial Physics in Germany and the lead author of one of the latest studies, said in a statement.

Grant's team for the first time detected a rare and slightly heavier version of carbon dioxide in a star's disk. The molecule's presence indicates that there is abundant carbon dioxide hidden deep inside the disk that Webb can't see yet, the authors wrote in their study.

First detections of benzene and possibly methane

RELATED STORIES:

— James Webb Space Telescope faces sensor glitch in deep space

— Why do some James Webb Space Telescope images show warped and repeated galaxies?

A different study that interpreted the spectra of another distant star called J160532 found its surrounding disk to be unexpectedly rich in hydrogen-carbon compounds, the strongest of which are hot acetylene molecules.

Other carbon-rich molecules spotted around the star include the first detections of benzene and possibly methane, astronomers say. If the latter turns out to be the case, it will be an exciting find because methane-rich worlds would have a possibility of manifesting in the star system. For example, in our solar system, Saturn's largest moon Titan occasionally features methane rains.

Water, however, was not detected in Webb's data on J160532.

"Instead, most of the water may be locked up in icy pebbles of the colder outer disk, not traceable by these observations," astronomers said in Thursday's statement.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur @Sharmilakg. Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.