James Webb Telescope question costs Google $100 billion — here's why

The James Webb Space Telescope has made a lot of incredible discoveries, but not the one that a Google bot suggested yesterday (Feb. 8).

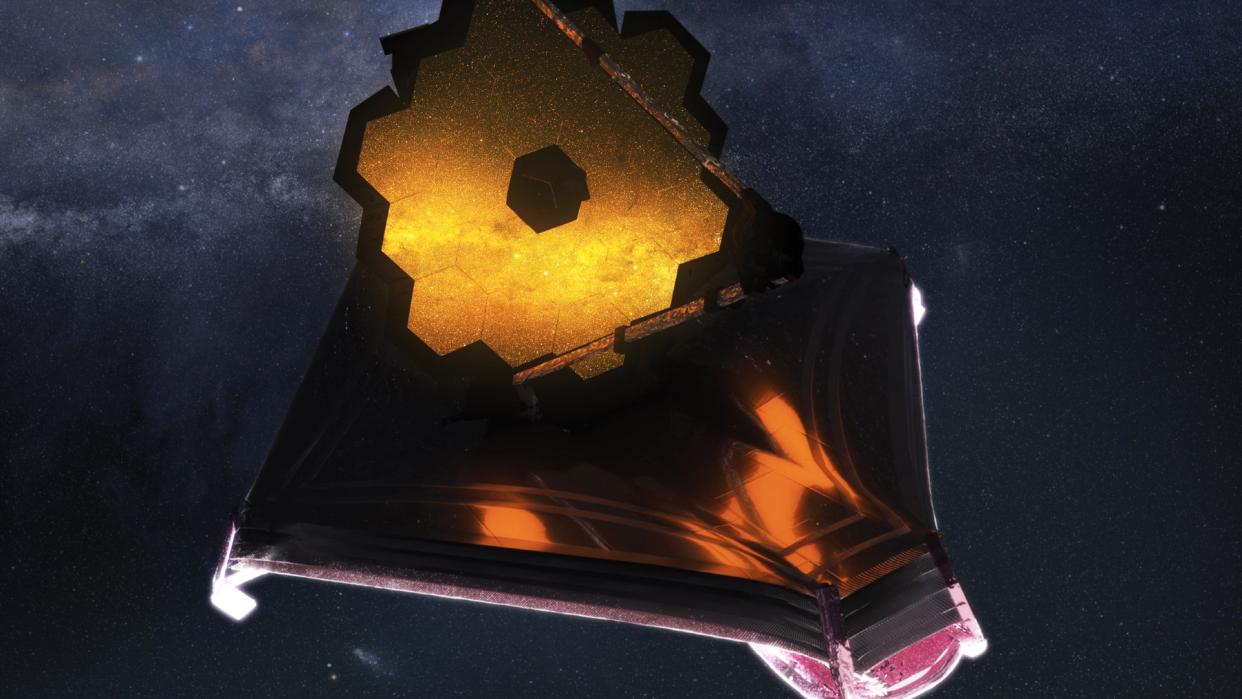

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (Webb or JWST) launched in December 2021 on a deep-space mission and became fully operational in July 2022. It's been scanning the cosmos and catching all kinds of incredible things: an accidental find of a space rock or asteroid, the historic agency DART mission that deliberately crashed into another asteroid, and unprecedented views of galaxies and the early universe.

But Google's hyped artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot, Bard, just attributed one discovery to Webb that was completely false. In a livestreamed event, blog post and tweet showing the test AI in a demo Tuesday, the chatbot was asked, "What new discoveries from the James Webb Space Telescope can I tell my nine-year-old about?"

The query came back with two correct responses about "green pea" galaxies and 13-billion-year-old galaxies, but it also included one whopping error: that Webb took the very first pictures of exoplanets, or planets outside the solar system. The timing of that mistake was off by about two decades.

Related: NASA's James Webb Space Telescope: The ultimate guide

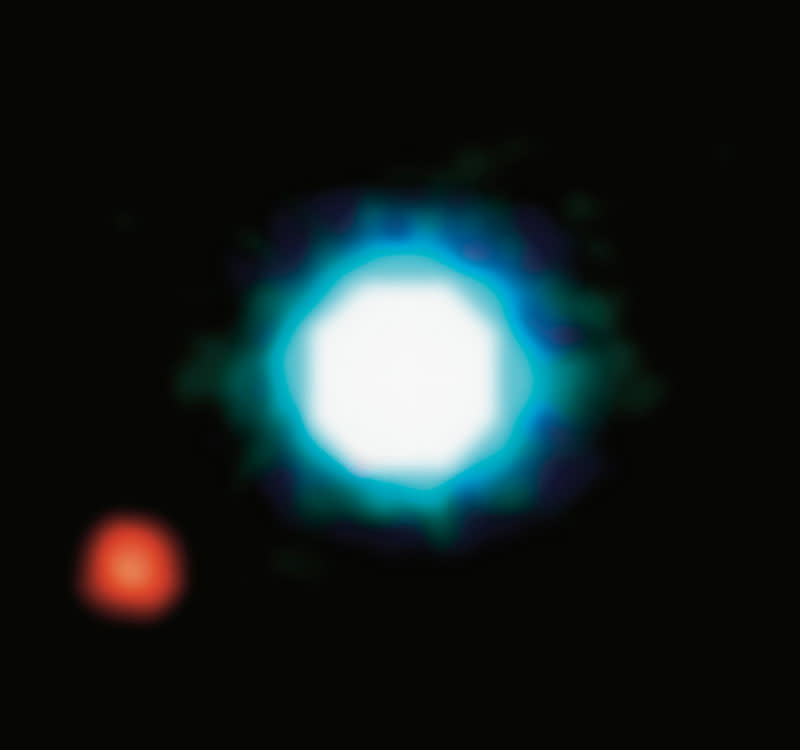

The actual first image of an exoplanet was released back in 2004, according to NASA. The incredible sight was captured by a powerful ground observatory, actually: the Very Large Telescope, a flagship facility with the European Southern Observatory in Chile.

That exoplanet is called 2M1207b. It is orbiting a brown dwarf, which is an object that is larger than a planet but not quite large enough to produce nuclear fusion to shine like a star. The image was no small feat: the planet's reflected light was imaged from 230 light-years away. (For perspective, the closest star system is about four light-years from us and yes, Alpha Centauri also has planets.)

Imaging exoplanets is notoriously difficult as they are mostly hidden in the bright glow of their parent stars. Most telescopes, Webb included, can only directly photograph exoplanets that are very large, the so-called gas giants larger than the solar system's largest planet Jupiter. These planets also have to orbit quite far away from their parent stars to be visible to the telescopes. Webb's first directly imaged exoplanet, HIP 65426 b, for example, orbits more than twice as far from its star than Pluto orbits from the sun. The absolute majority of the currently known more than 5,300 exoplanets has not been directly imaged, but revealed their presence through the minuscule dimming of their parent stars that takes place when the planet passes in front of the star's disk.

The embarrassing error for Google caused the search giant's parent company, Alphabet Inc., to lose $100 billion in market value Wednesday, according to Reuters. Industry observers fear that Google is quickly losing credibility to rival bot creator OpenAI, a startup heavily supported by fellow search giant Microsoft (which produces Bing).

OpenAI's ChatGPT was released in November 2022 and can produce remarkably human-like text, even in different writing styles. Just the day before Google's blunder, in fact, Microsoft said there was a version of the Bing search available that has some of ChatGPT's functions integrated.

That said, ChatGPT is not immune from error either. Last week, National Public Radio asked the bot to do some simple rocket science. It sounds like the result was worse than a beginner in the physics-inspired Kerbal Space Program game that trains folks how to launch rockets.

The bot was asked, for example, to produce a fundamental mathematical equation for rocket science called "the rocket equation." When real-life rocket scientist Tiera Fletcher read the result, her laconic response to NPR was this: "It would not work. It's just missing too many variables."

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.