Japan Starts Releasing Treated Radioactive Water From Fukushima Into Ocean

An aerial view shows the storage tanks for treated water at the inactive Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan on Aug. 22.

Japan began pumping treated radioactive water from the defunct Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear power plant into the Pacific Ocean on Thursday, capping off a yearslong saga that pitted fearful local fishermen and neighboring countries against Tokyo officials and scientific evidence showing that releasing the water poses less danger than keeping it in storage.

In March 2011, a tsunami flooded the generators powering the backup cooling system for the reactors at the atomic power station on Japan’s northeast coast, triggering the worst nuclear meltdown since 1986’s Chernobyl. Since then, the Tokyo Electric Power Company has continued circulating cold water through the disabled reactors to keep the radioactive fuel cool.

It’s a routine process employed by most of the 400-some commercial nuclear reactors operating in the 32 countries that use atomic energy. Once the water cycles through the reactors, utilities such as TEPCO filter out the most dangerous radioactive materials that form during the splitting of uranium atoms. One major radioisotope remains: tritium, a radioactive form of hydrogen that is virtually impossible to strip from water.

Too weak to penetrate human skin, tritium is considered one of the least harmful radionuclides. There is no data that shows tritium causes cancer in humans, though experiments on mice forced to ingest very large daily doses of tritium throughout their lifetimes tended to develop cancer and die younger than their counterparts who hadn’t, according to a 2021 paper in the Journal of Radiation Research. Tritium is difficult to detect in the environment, making large-scale epidemiological research challenging. To play it safe, regulators around the world have typically set limits for releasing tritium into waterways at levels far below than what naturally occurs from cosmic rays ― and even lower than what sewage treatment facilities spew into rivers, bays and oceans.

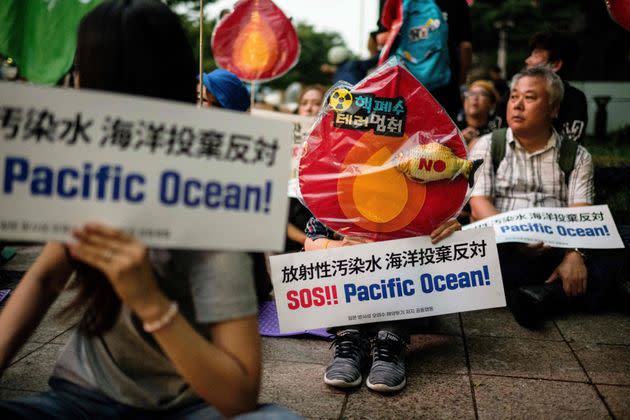

A South Korean activist holds a placard that reads "SOS!! Pacific Ocean!" during a protest against the planned release of wastewater from Japan's stricken Fukushima nuclear plant into the Pacific, outside City Hall in Seoul on Aug. 22, after Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida announced the release will begin on Aug. 24.

As such, nuclear operations typically just dilute so-called tritiated water and release it into large waterways where the isotope is indistinguishable from naturally occurring levels of tritium. Outside of anti-nuclear activist circles, where decontextualized information about the risks associated with atomic energy is rife, these routine releases of tritium usually garner little attention.

But over the past 12 years, TEPCO has accumulated more than 1 million metric tons of tritiated water in tanks stored in Japan — enough to fill 500 Olympic-size swimming pools. Those stockpiles are nearing capacity and, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency, risk another accident if an earthquake or giant wave causes the tanks to leak tritium in uncontrolled volumes.

So, after lengthy debates, the Japanese government decided to pump the heavily diluted tritiated water into the Pacific.

“The main problem with the release is that it sounds bad. But it actually isn’t,” Nigel Marks, a physicist and nuclear expert at Curtin University in Australia, said in a statement. “Similar releases have occurred around the world for six decades, and nothing bad has ever happened.”

Ironically, the very people drawing attention to the Fukushima releases are those who face the most potential harm from fearmongering over tritium. And an uproar that results in further turning away from nuclear energy will almost certainly guarantee more use of fossil fuels with devastating ecological consequences.

The continuing concern is like shooting yourself in the foot; the more you complain about it, the more people are going to assume there’s a problem even though there isn’t.Paul Dickman, senior fellow at Argonne National Laboratory

Among the loudest local opponents of Japan’s plans are fishermen who fear the releases would trigger bans on imports of their seafood, much as neighboring nations blocked shipments of some Japanese farm products after the Fukushima accident.

“The continuing concern is like shooting yourself in the foot; the more you complain about it, the more people are going to assume there’s a problem even though there isn’t,” said Paul Dickman, a senior fellow at the Argonne National Laboratory, the U.S. government’s premier nuclear research center. “For me at least, the problem has been that people don’t actually read what is being proposed.”

The French nuclear fuel plant at La Hague discharged more than 12 times the total content of all the tanks in Fukushima in 2018 alone without harm to people or the environment, according to Tony Irwin, a nuclear engineer at the Australian National University.

South Korea’s Kori nuclear power plant discharged more than four times as much tritium into East Asian waterways as Japan plans to release from Fukushima. Still, nearly 8 in 10 South Koreans told the pollster Gallup in June that they were worried about Japan’s plan. The government in Seoul loudly protested the Fukushima release for months before finally relenting in July, announcing that its researchers had determined that the amount of tritium would be “less than 1/100,000th compared with the level in the surrounding waters gauged in 2021, which is scientifically negligible.”

“More tritium is created in the atmosphere than is produced by nuclear power reactors, and it then falls as rain,” Irwin said in a public statement. “Ten times more tritium falls as rain on Japan every year than will be discharged. The discharge limit for release of radioactive water at Fukushima is 1/7th of the World Health Organisation standard for drinking water. The discharge is ultra-conservative.”

The tsunami-disabled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant is seen from Namie Town, Fukushima prefecture, Japan, on Aug. 24.

China’s fast-growing fleet of nuclear reactors discharges huge volumes of tritium into waterways each year. Yet, in a move widely seen as part of China’s geopolitical jockeying with its former colonizer and regional rival, Beijing emerged as the most vocal national critic of Tokyo’s decision. At a press conference on Tuesday, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin called Japan “extremely selfish and irresponsible” and accused its World War II-era foe of treating oceans meant for the common good of humanity as a “sewer for Japan’s nuclear-contaminated water.”

Earlier this week, the partly self-governing Chinese city of Hong Kong slapped restrictions on imports of Japanese seafood and seaweed.

The fight over tritium isn’t just happening in East Asia.

In the United States, New York and Massachusetts passed state-level laws to block the company Holtec International from releasing tritiated water from two shuttered nuclear power stations near New York City and Boston. Since the radiation falls under federal jurisdiction, the statutes are likely to be overturned in court. But the episodes show how controversial the issue remains, with local news outlets characterizing the proposed discharges as “dumping radioactive waste” into waterways.

But unlike so-called “forever chemicals”— per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, which resist water and oil and are widely used in nonstick materials and firefighting foam, and were only recently recognized as major cancer-causing pollutants by federal regulators — radiation and its effects have been picked over for over a century, said Kathryn Higley, a radiological health scientist at Oregon State University.

“We’ve been studying radioactivity for more than 100 years. We have a pretty darn good idea of what the effects of radiation are and what the doses are needed to cause those impacts,” she said. “The dose makes the poison. It’s not radioactivity — that’s everywhere from natural sources. It’s how much of it is being released and where is it going.”