This Japanese eatery in downtown Phoenix is a window into the past: 'Always feels the same'

At the corner of Central Avenue and Willetta Street sandwiched between the sprawling, glass paneled Circa Central apartment complex and the glistening Burton Barr Library sits a one-story 1960s utilitarian brick building.

For over four decades, Phoenix Blue Fin has been serving Japanese comfort food. Since it opened in 1981, residents from all over the Valley have passed through its doors. On weekdays, there is still a steady rhythm of cars picking up food to go from its small drive through window, people coming and going through the front door and the smell of cooking meat lingering in the parking lot.

While the small eatery has held fast against the onslaught of the Valley’s urbanization, success has never been smooth sailing for Phoenix Blue Fin's owner Betsy Yee, 88, a second-generation Phoenix resident.

During her tenure as the owner of the property, she has seen the area transform before her eyes and her property’s value skyrocket. With this came many encroachments —developers and the city trying to buy the land, construction of the Valley Metro Rail project and the Covid-19 pandemic. At times she’s also had to endure the not-so-subtle reminders that people like her weren’t always welcome in this part of Phoenix.

Yee may only be 4-foot, 11-inches tall, but she wields an outsized character and personality that relishes a challenge. When asked how she’s stood up against the forces of change that have, on more than one occasion, nearly cost her the business, her answer is simple.

“I’m Betsy Blunt.”

‘This place looks the same. This is the way it's always been'

During lunch hour on a recent Tuesday, Lyn Yee, Betsy’s daughter, and Angelica Cruz who's worked at Blue Fin for 20 years were juggling multiple tasks. They greeted customers like old friends as they took orders for the restaurant’s staple dishes like chicken teriyaki, panko chicken, vegetable yakisoba and pork katsu prepared by Jose Botello, Blue Fin’s cook of 32 years. Many dishes come with a side of steamed rice and vegetables served in styrofoam bowls or plates. Prices range from $7.95 up to $12.95.

“Hey, how was the wedding?” Lyn asked a man browsing the printed paper menus pasted above the drive-thru window.

The modest, fluorescent-lit dining room buzzed with lunch time activity. Several people sat on the blue and yellow hard plastic chairs waiting for their orders while others tucked into their meals.

“This was always one of our favorite spots,” said Eddie Verdugo, who has been coming to Blue Fin since he was in high school in 1994. “The mom used to run it and she was the most polite lady I have ever met. She was super nice and we loved her,” he said, remembering a time when Betsy Yee ran the counter.

Verdugo, along with his wife and son, ordered their go-to lunch favorite and the restaurant’s top-selling dish, a smoky chicken teriyaki with a generous helping of steamed rice and a side of fresh vegetables.

A resident of South Phoenix, he says that while much of the surrounding area has changed, the restaurant and its food are just as he remembers. Like most people who frequent the Blue Fin, that familiarity and lack of modern touches is as much of a draw as the food and prices.

“We didn’t have a light rail and it was a lot emptier in this area and nothing was around here,” he said. “But this place looks the same. This is the way it's always been. They just keep up with it.”

A bygone era: The last flower shop on Baseline Road tells a story of family resilience

The story of ‘The Incredible Blue Fin’

Betsy entered Blue Fin as the lunch hour was subsiding, her purse dangling on her wrist and a pearl necklace draped over her floral dress.

In her hand she carried two pieces of lined notebook paper. On the top of one of the pages she had written the words “The Incredible Blue Fin.” With a wry smile she warned that she might talk too much, so she had decided to put her story to paper.

“I’m going to read this to you first,” she said.

As Betsy tells it, the story of Phoenix Blue Fin goes well beyond opening a beloved family-owned eatery.

In 1979, after raising her children in California, Betsy decided to move back to Phoenix, where she was born and raised, with her husband Howard to help care for her aging parents, Chinese American immigrants and pioneering Phoenix residents.

She saw an ad in The Arizona Republic that 1401 N. Central Ave. was up for sale and went to Phoenix City Hall to bid on the property. She recalls being the only woman in the room with five other "very nicely dressed men in suits."

“They would state a sum and I would state a sum much higher,” Betsy said. “It just kept going. Then next thing I knew, I had the property.”

Betsy said the attraction of the property had nothing to do with its value.

“There was a period when this property wasn’t valuable,” Betsy said. “(But) we could never buy it. We as Asians were not allowed to live on Central Avenue,” she said, referring to the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) that formed in 1933 with the goal of making it impossible for people of color to purchase real estate in many areas of Phoenix.

A dark history of redlining in Phoenix

Betsy was born and raised in Phoenix at a time when segregation and discriminatory practices in land and home ownership were the law.

The HOLC group made color-coded maps that labeled the riskiness of giving loans or services in certain areas of a city and areas color coded as red were deemed as hazardous or undesirable — a tactic known as redlining.

According to a 2021 report called "A Brief History of Housing Policy and Discrimination in Arizona" by ASU’s Morrison Institute for Public Polices the criteria created by realtors, loan officers, appraisers and real estate agents included quality and age of buildings, the surrounding landscape and “threat of infiltration from foreign born, negro, or lower grade population.”

“Minorities were either steered away by real estate agents or they simply would not be allowed to purchase the property or to lease the property from the current owner or the person who controlled the lease,” said Rashad Shabazz, associate professor at Arizona State University specializing in race and geography.

“In a lot of respects, that's what happened here in the Phoenix metropolitan area,” Shabazz said. “And it's one of the main reasons that Asian American immigrants in general, particularly Chinese immigrants, found themselves south of Washington Avenue in the Black and Brown neighborhoods. They were kept out of purchasing or renting land above Washington Avenue. And all above that was white Americans, and a very small number of Mexican American households. But it was overwhelmingly white. It was an exclusive neighborhood. And people of color could not either do business or they could not run a business or live above that area because banks wouldn't give them loans.”

While the Arizona Republic found that there were never racial covenants on the deeds of 1401 Central Avenue, according to a 1930s Phoenix redlining map the property was in an area Chinese immigrants and other minorities were steered away from.

Did Phoenix segregate where minorities lived? Find out with Valley 101 podcast

How Betsy’s father paved the way for other immigrants

These systemic hurdles didn't stop Betsy’s father from pursuing his American dream in Phoenix. Dea Hong Toy emigrated to the United States from Canton, China (now called Guangzhou) in 1915 and worked on the railroads in California before moving to Phoenix in 1923.

In the Valley he worked as a vegetable peddler hauling produce to various businesses, like the Biltmore and other resorts, and even delivered to tuberculosis sanitariums north of Phoenix. He later opened a grocery store at 16th Street and Camelback Road. In 1930 he co-founded the Chinese Chamber of Commerce and was instrumental in creating protections for Chinese American businesses.

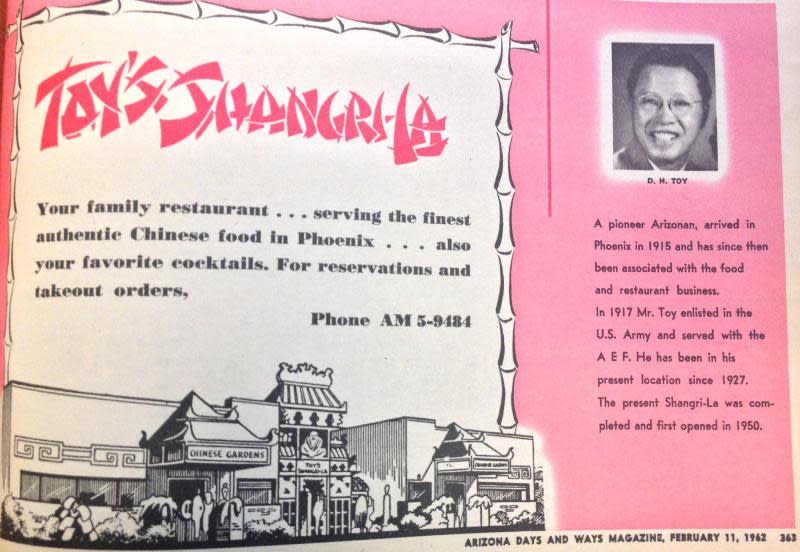

He also opened the Toy's Shangri-La, one of the biggest Chinese restaurants ever seen in Phoenix at the time and one of the first to serve a largely non-Chinese clientele. Within a generation Toy had become one of the most successful Chinese businessmen in the history of the city, according to a Phoenix Asian American Historic Property Survey from 2007.

Betsy, one of 11 children, recalls working at Toy's Shangri-La with her siblings and credits learning the value of hard work to that time, though she also recalls the daily discrimination her parents faced.

“People would picket in front of the building and they wouldn't let people pass into the restaurant," she said. “The discrimination we don't speak of now, but it was there and we had difficult times. My parents never really said a whole lot about it. We just kind of lived it.”

How Betsy ended up back in the restaurant business

Before Betsy took over the property, the building on Central had served as a house and even a drive-thru laundromat. She began renting out the space only to go through several tenants including a book company that never paid rent and a printing company. Then a Japanese man who spoke little English whom they called Mike-san approached her about opening a Japanese eatery called Blue Fin.

“When he took over, I was so happy,” Betsy said. “I had the crummiest people renting from me.

"He was so incredible,” Betsy said. “If you gave him a cube of ice he could carve it into a swan, he could carve it into a bear. He had an innate ability. He made the best sushi in the country. But sushi was not popular when he first started. It was a novel thing.”

Along with sushi Mike-san started offering Japanese staples like miso soup, katsu pork, Japanese chicken curry, chicken teriyaki and gyoza.

However, In 1991 Mike-san had to move to California due to a personal problem and he left Phoenix Blue Fin to Betsy and her husband.

“Before he left me with this whole thing, he personally took the young chef that he worked with him in the kitchen and taught him everything," Betsy said. "Now he’s worked for me for over 32 years. He hasn’t missed a day, does not give any excuses and is very loyal."

One of the only changes Betsy made was getting rid of the sushi and adding what is now the restaurant's second best-selling dish, panko chicken — chicken breaded in panko crumbs served with a side of rice with a choice of dipping sauces like teriyaki, sweet ‘n sour, tonkatsu or chili.

“Back in the old days and even today fish was so costly,” she said. “And it can go bad quickly.”

But food costs have been the least of her challenges over the years.

The light rail was almost the end of Blue Fin

While the restaurant has become a regular stopover for locals from around the neighborhood and people from all over the Valley, the family has had to survive many challenges. In 2006 the construction of the light rail meant that part of Central Avenue was closed, making their business inaccessible. Many other businesses in the area shut down because of it, Betsy said.

As part of the project, the land where her restaurant was built, unbeknownst to Betsy, was being considered for eminent domain to accommodate the construction. In 2006 Betsy told the Arizona Republic that she was bewildered about the city’s proceedings and how they had only offered to purchase her property for a fraction of the price.

“The city put my property up for sale without my knowledge,” she said.

According to Lyn, customers of Blue Fin created a petition to save the restaurant, which they eventually presented during a public city meeting in 2006. The petition worked.

"A few weeks later the mayor’s office even called to apologize," Betsy said.

Betsy later fought the city when they decided to put parking meters on Willetta Street in front of the Blue Fin. Betsy saw the meters as detrimental to her customers' ability to visit.

“If somebody was trying to punish my business by putting parking meters there so my customers couldn't park, that’s not fair,” Betsy said.

The city eventually took them out after she complained.

Betsy developed such a fierce reputation that city officials no longer wanted anything to do with her.

“Others would not see her,” Lyn said laughing. “They would see her name and they would be like ‘oh we ain't touching that.'"

How streetcars changed Phoenix: And where you can still see them today

The pandemic forced Betsy to pass the torch

Betsy and her husband Howard worked at Blue Fin every day up until the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. According to Lyn, Betsy was face of the restaurant working the counter while Howard worked behind the scenes running errands and shopping for the establishment.

Since then Lyn, an engineer by education who got her bachelor's at MIT and a master's in business at the University of Texas at Austin took over the day to day running of the business after 14 years working side by side with her parents.

One of five siblings, Lyn said helping each other is how it's always been. She had worked several times at the eatery when she was in high school and she has also seen several of her siblings pitch in at the restaurant. Lyn said even her mom’s sister Violet Toy worked for years at Blue Fin until she was 89.

“During the Matsuri Festival (an annual Japanese cultural festival in Phoenix) that’s when I really pressure my family to help out,'' she said. “If you come to the Matsuri festival you might see all of my relatives or their friends working at our booth.”

But while her parents have taken a back seat to running the restaurant Lyn admits it’s taken a few years for her and her mom to see eye to eye on how things operate.

“I’m an engineer and she's an artist, so we used to butt heads when I first started,” Lyn said. “But I have personally learned to trust her instincts and know that she is right more often than I think she's wrong. I think the same goes for her. She sees I’m not just being a contrarian, but I have a reason for the things I do. And as you age you realize how smart your parents are.”

Occasionally Betsy still comes in to take a look at things and give her two cents.

“My mom is really good at seeing the big picture. She will say, 'Oh you know this is a trend, we should add that.' That’s why panko chicken is on the menu. She was like ‘People like fried food and we should add panko chicken.’ And now it's our second biggest seller.”

While their styles differ, customers know that Betsy and Lyn have one goal in common.

“Their common ground is they both want to help people and serve and provide them good products at reasonable prices,” said a regular who overheard the conversation.

The future of Blue Fin

As all around them Phoenix continues to grow, Lyn has plans to stick to the tried and true approach that has allowed Blue Fin to survive for four decades, and that allowed her family to thrive in the Valley for nearly a century — keeping the prices as accessible as possible, and everything else simple, tasty, friendly and family oriented.

For customers like Chandler resident Phil Dugan, who discovered Blue Fin when he worked at an outpatient center on 11th and McDowell road, it's the community feel and consistency that have kept him coming back for 40 years.

“It always feels the same,” Dugan said. “I know everyone when I come in here. When you have a business that’s been established this long, there’s no cliches, you take care of the people that take care of you. That’s how it feels here. If you live with that philosophy you go far in life.”

Luckily for Dugan and the other regulars at Blue Fin, the family has no plans to sell.

"I will do my absolute best and keep what people want and hopefully it works out," Lyn said. “I think it makes a big city seem personal. When you have small business it makes a big city seem like a small city. People know you and they love that.”

And Betsy has taken steps to make sure the Blue Fin building always stays in the family.

“That's the one thing I'm going to put in my will that Lyn could lease it out, but I never want them to sell it,” Betsy said.

When asked what she tells the never-ending stream of developers knocking on her door to see if she wants to sell the property, Betsy responds with a characteristically blunt answer.

“I tell them goodbye.”

As this story was being reported, Howard Yee, passed away at the age of 89 on Oct 16, 2022.

You can connect with Arizona Republic Culture and Outdoors Reporter Shanti Lerner through email at shanti.lerner@gannett.com or you can also follow her on Twitter.

Support local journalism like this story by subscribing today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Phoenix restaurant Blue Fin survived racism, building booms and more