How Jefferson County schools turned it around, escaped state control

On a recent weekday morning, Jefferson County K-12 School – located on the edge of downtown Monticello on U.S. 19 – is bustling with students in the hallways wearing backpacks with their favorite cartoon characters and laughing with friends.

Outside, just 35 miles east of Tallahassee, the rural setting is a vision of oak trees covered in Spanish moss, vintage shops, abandoned buildings and historic landmarks on almost every corner.

Inside, a fully staffed faculty is preparing for classes in a building with hallways featuring inspirational slogans touting “Tigers” pride and student success.

In many ways, the school of 700-plus students once again has become a community driver for this rural community dubbed the "keystone" of Florida's Panhandle, an image of the old southern charm that helps define North Florida.

But it wasn't always that way. In 2023, the school earned a C grade, marking a giant step forward after a string of Ds and Fs over the last 20 years.

More importantly, it serves as a kind of vindication for local control after the state's bungled experiment to create a charter-run district. In 2017, the state took over the county's school district after years of poor student success and financial woes.

"We believe that all children can learn, and all children can be successful, regardless of their background or what's happened in their lives, and for me, this was a chance to prove it," Principal Jackie Pons said during a recent interview on campus with the Tallahassee Democrat.

The "we" Pons is referring to is the Jefferson County community and the team of certified and dedicated teachers he aggressively recruited when he took the helm in 2022. He says if not for their hard work and dedication, the turnaround wouldn't have been possible.

A struggling school district

Here's what happened: In 2015, concerned parents, teachers, students and others wrote a letter to then-Gov. Rick Scott, asking for assistance from the Florida Department of Education with the struggling school district as the school year was coming to a close.

"We value how important our children's education is for a sound future and are passionate to 'take back' our schools," the letter read. "We feel the education system in our county is broken. We are asking for your help in getting our school district back on track for the sake of our children."

Among their concerns were poor student achievement and questionable spending. They attached a petition with 250 signatures. The district had two public schools at the time, an elementary school and a combined middle-high school. That year, the elementary school received a D and the middle-high school got an F.

The letter detailed the district's decades long reputation of performing in the bottom 10% of Florida school districts, an alleged shortfall of $320,000 due to 50 students leaving the school district during the school year and claims of a lack of transparency between the local school district and the community.

The letter was passed along to an investigator with the Department of Education, who asked former Superintendent Al Cooksey for a response. He addressed the concerns but encouraged residents to "get involved."

That wasn't enough for state education officials.

The takeover by the state

Years later, the state later handed control of the school district to Somerset Academy, Inc., a nonprofit charter school company based in Pembroke Pines, making the district the first and only in the state to ever be fully operated by a charter company.

The private company entered into a five-year contract with the district and was charged with reversing failing grades, addressing staffing problems and establishing accountability of tax dollars.

The first order of business was to move the elementary school students to the middle-high school campus, combining all the grade levels at the current Jefferson K-12 School location. Students wore Somerset school uniforms, light blue polo shirts and khaki slacks. The company also added a culinary lab and renovated the basketball courts.

But from 2017 to 2022, the charter school remained troubled by students' lagging academic performance and mounting disciplinary issues, like fighting that in one case led to the arrest of 15 students.

Lurking behind the scenes were still bigger issues.

A puppet for behind-the-scenes politics

The school district was still getting a D grade. There were so many fights, one teacher said it was smothering the learning process for many students. The state made plans to bring in yet another external operator — without following legal procurement practices, according to an investigation by the Tampa Bay Times/Miami Herald.

The newspapers' coverage found the education department was in talks with a private company to operate Jefferson County Schools, one that was in place to win a multi-million-dollar contract before the bidding process even began.

Documents said the request for a bid was customized for MGT Consulting Group, run by former Republican lawmaker Trey Traviesa of Tampa, a friend of then-Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran.

MGT Consulting's money was already set to be covered by COVID relief dollars, according to Rep. Allison Tant, D-Tallahassee, who called for an investigation in January 2022 into the education department's plans in Jefferson County, which is in the legislative district she represents.

The political drama led to an internal investigation, resignations at the Florida Department of Education, and finally the release of the school district back to the community.

As five years of charter company control was coming to an end, Somerset decided not to renew its contract with the school district. Pons, a longtime former Leon County Schools superintendent, was hired as principal of Jefferson County K-12 School by the local school board.

Another transition began.

The return to local control

The hand-off back to local control was approved in February 2022 under one big condition — the district had to raise its school grade to a C in the following year.

It did.

In its 2023 school grade from the Florida Department of Education, the rural county school earned a C grade after decades of Ds and Fs, and was released from the oversight of the state's Bureau of School Improvement.

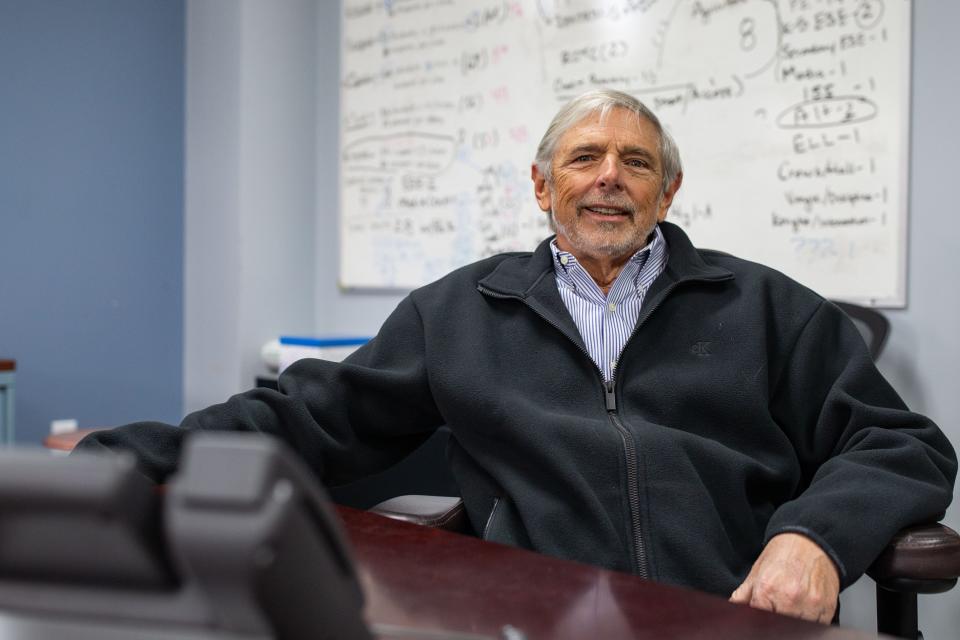

Pons, who led the turnaround effort, said he was having doubts about accepting the daunting task of leading the school: "I remember 60% of the teachers weren't certified, fights were everywhere, and it was out of control," he said, seated in a conference room near his office.

Pons started his career in education in 1986 at Rickards High School where he was a teacher, athletic director and assistant principal. He later became assistant principal at Godby High School and then principal at Deerlake Middle School. He was first elected superintendent in 2006.

His career was upended in 2013 when an anonymous notebook — later revealed to have been authored in part by his then-rival Rocky Hanna, the current superintendent — alleged he was involved in a variety of misdeeds, including favoritism in the awarding of construction contracts. The notebook found its way to the FBI which, along with the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, launched an investigation the next year.

In 2018, the FBI cleared Pons and said no charges would be filed. But two years earlier Pons was defeated by Hanna in a blowout election in which the investigation was a forefront issue. Pons went on to work in the private sector and taught at Florida A&M University's Developmental Research School before being tapped for the post in Jefferson County.

"After losing the election in Leon and going into the private sector, I wanted to finish my career in education," Pons said. "So, I figured, why not try the toughest job in the state. Let's see what we can do if we build the right team."

Pons said he interviewed more than 100 teachers during the summer of 2022 and hired over 50 new teachers. As of this month, the school is fully staffed and only has an opening for a music teacher. Pons said he asked each teacher candidate: "Are you ready to climb this mountain with me?"

Most of the teachers hired by Somerset lacked state certification and were considered permanent substitute teachers.

Pons had three priorities: Recruit certified, highly effective teachers, let them make curriculum decisions in the classroom and grow the student population. By expanding athletic programs, reinstating student government positions and offering career and technical education classes, he is hoping to lure students back to the school from neighboring counties, and in turn bring in more state dollars.

School districts receive legislative funding based on how many full time equivalent (FTE) students are enrolled. The more FTE students a public school has, the more money it is likely to receive from the state to put toward materials, staffing and resources.

He said they started this school year with 700 students. As of Feb. 5, there were 715 students enrolled. In 2015, before the state takeover, there were 850 students enrolled, and under Somerset's control in 2022, there were 734.

The district first started losing students after it was forced to integrate in 1970, 16 years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision triggered integration across the south. White parents opted to send their kids to Aucilla Christian, a predominantly white private school in the county, or to Leon County instead of integrating.

The county has the second largest percentage of students that attend private school in the state at 38.2%.

Pons and others hope renewed bonds with the community will draw even more students back to the school.

By mid-2023, the school was named a community partnership school, a model started by the Children's Home Society of Florida designed to address barriers to student learning success by providing families with basic necessities like food, clothes and healthcare.

Rep. Tant was instrumental in making the partnership a reality and getting the school moved up on the priority list.

Meeting the requirement of having four partners on a 25-year contract, the school has teamed up with Florida A&M University, Florida State University, North Florida College and the Department of Health to, as Tant has said, "change the trajectory of these students' lives by providing wrap-around services for them and their families."

The community support returns

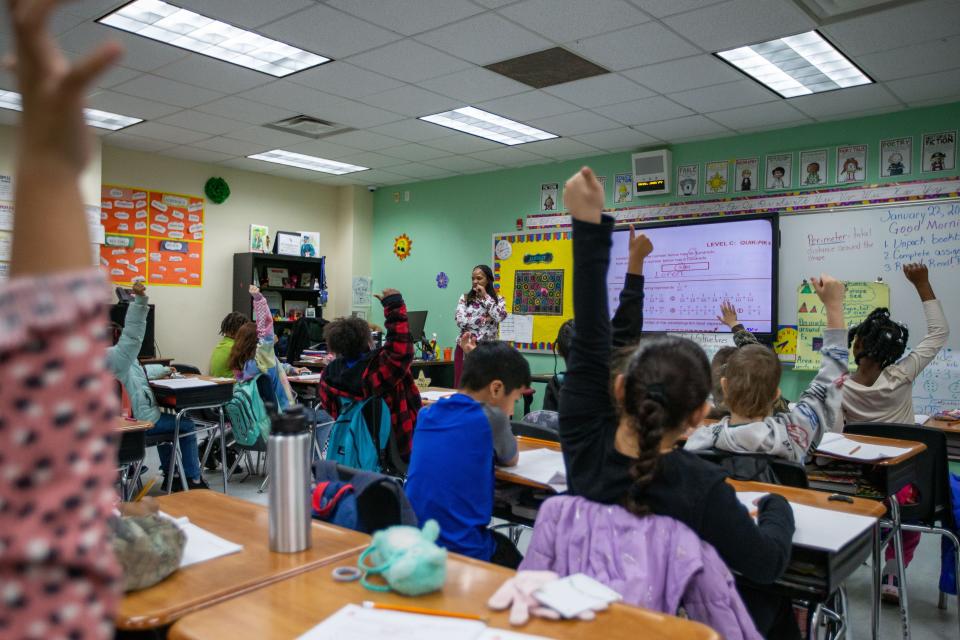

The school was a lost cause to so many who came before Pons, including teachers. One teacher, Willet Boyer, taught at the school while it was chartered by Somerset Academy. He said discipline and classroom management were some of the biggest issues at the school.

"Now I see a difference in student attitudes, and I see a difference in the atmosphere around school," said Boyer, who credited Pons' efforts in leading the transformation. "You're looking at teachers that are teaching more enthusiastically, more confidently and the students are learning more as well."

Blambie Fils started her teaching career at Jefferson in 2021 after graduating from Florida A&M University and was hoping to prove herself as an effective educator. The same year she started, her class of fifth graders had some of the highest proficiency rates in the school's history.

"I didn't realize how good it was until I looked at the history of Jefferson," Fils said. "It wasn't always about work, but we built a routine that was academically centered."

Local residents are echoing the hopes about the future of the school district.

"We're just having the biggest celebration right now," Eddie Yon, a local pastor and volunteer at the school for over 15 years, told the Tallahassee Democrat. "We got our school back and it feels so good because no one loves Jefferson County like Jefferson County."

Floyd Faglie, president of the Monticello-Jefferson Chamber of Commerce, added that his organization "is excited about the future of our public schools and expects the gains in achievement to continue."

Some current parents, many of whom recall attending classes at Howard Academy, the old Black-only school under segregation, or the former Jefferson County Middle-High, prefer that older and younger students stay on separate campuses.

But they don't deny the progress being made at the school as a single unit.

"I liked it better when I was in school because it was separated, and there was not so much altercation. It's just more work for the teachers," parent Denetria Mack said. She has three students at the school in grades 10, 7 and kindergarten. "I give them much props though because it can't be easy, and I pray they can go up to a B or even an A."

Pons said the district is already headed in that direction. Results from second-round progress tests show higher scores than last year's.

"We're hoping to get a high C or a B next year," Pons said. "We never expected that C, so we'd be pretty excited about that."

Alaijah Brown covers children & families for the Tallahassee Democrat. She can be reached at ABrown1@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: How a Jefferson County, Florida, school escaped from state control