Jeffrey Epstein's Jailhouse Suicide Is More Feasible Than You Think

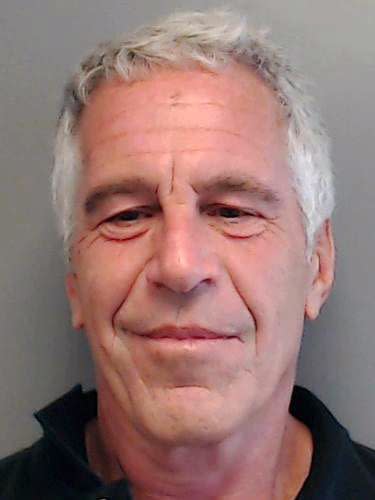

In the wake of Jeffrey Epstein’s death this past weekend, I’ve watched, on the television in my cell at Sing Sing, a parade of talking heads express everything from confusion to anger that such a high-profile person could kill himself while in custody. Such disbelief surprises me. Setting aside the question of whether Epstein did, in fact, commit suicide—I leave that to the authorities and the conspiracy theorists—let’s be clear: High profile or not, if you want to kill yourself while in custody, you can find a way.

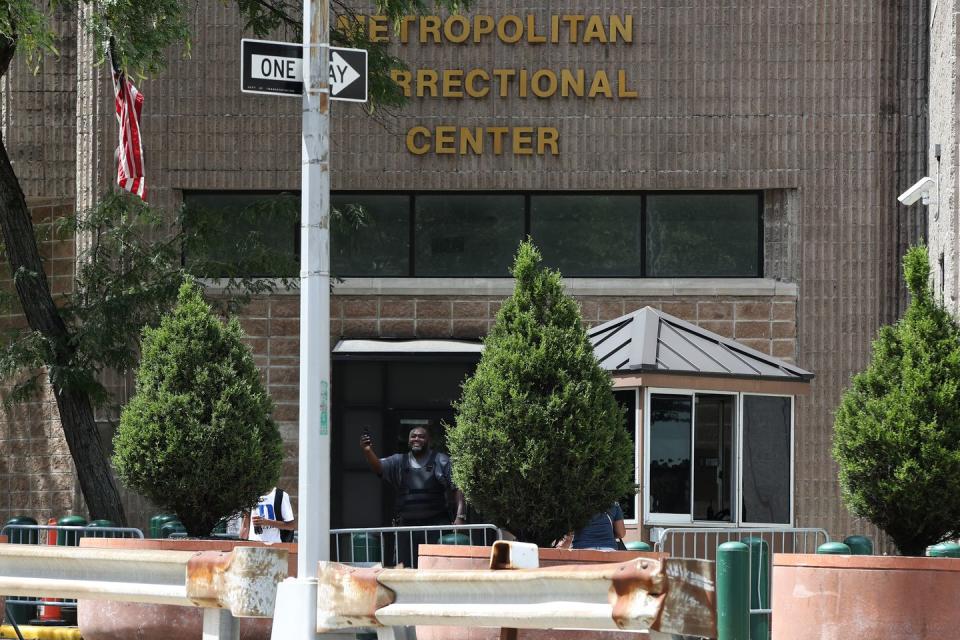

Presumably, Epstein was not diagnosed with a serious mental illness; such inmates are the hardest to monitor for self-harm. Like all jails and prisons, at the county, state, and federal levels, Manhattan Correctional Center, where he was held, was not equipped to watch his every move. On July 23, guards reportedly found him unresponsive, with bruises on his neck. They put him on what’s known as suicide watch. There, he would’ve been housed in a special cell, perhaps surrounded by plexiglass windows, devoid of anything he could use to harm himself. He would also be under round-the-clock observation. His activity would’ve been logged. He would’ve undergone daily psychiatric evaluations; those would’ve been logged, too.

Six days after he was placed in the tank, as we in prison call it, he was taken back out. For that to happen, at least by the books, a psychologist would’ve determined that he was no longer a risk to himself. Epstein was moved back to the special unit where he’d been held prior to the tank, where it would’ve been almost impossible for MCC staff to watch his every move. (That doesn’t excuse the guards on that unit the night he died, who’d allegedly fallen asleep and later fudged the books.)

In the eighteen years I’ve been incarcerated, I’ve heard countless stories of suicide attempts. All of them happened swiftly, under the radar. When I was on Riker’s Island, certain inmates worked as suicide prevention aides. The SPAs made rounds on the 11pm to 7am shift, while the guards sat on their asses. The gig came with perks, such as using the phone and watching late-night TV in the day room. I recently spoke with Blanco, a former SPA who’s now with me at Sing Sing. He told me, “One time, a bugout”—prison slang for people with mental illness—“threatened to hang himself if he didn’t get a cigarette.” Blanco said he blew him off at first, then doubled back a few minutes later to check in. He found the guy hanging from a sheet tied to the light fixture. Blanco yelled for the guard, who popped the cell and cut the sheet with a hook knife, a tool expressly issued for that purpose.

I’ve also seen it firsthand. One snowy day in January 2010, at Attica, where I was held at the time, a guy who hailed from Brooklyn, like me, and whose parole year, 2029, was the same as mine, returned to his cell on E Block after tossing around a football in the yard and hanged himself. It was the middle of the day, and inmates and guards were up and down the tier, yet no one saw him do it. In 2013, on the same cell block, on the same tier, another acquaintance hanged himself. He’d been the most talented artist I’ve met in prison. Using wettened bread, dry spaghetti, and other food, he’d sculpt dead-ringer caricatures of the guards. The night he died, he’d spent hours talking to the guy in the neighboring cell, who later said he never saw it coming.

Even inmates that we know are at a very high risk of suicide are difficult to monitor. Over the years, I’ve worked a few stints as an aide on units for inmates with serious mental illness. I’ve heard about men attempting self-harm in all sorts of creative ways. Some swallowed razors or detergent balls. Others snapped the blade out of their prison-issued BIC razors and used it to cut their neck, their wrists, their penis. If they survived, these guys were placed on suicide watch, sometimes for days, sometimes for weeks, until their crisis subsided. Once out, they couldn’t be watched 24/7, and many of them cycled in and out of the tank.

I’ve experienced suicide watch as a patient, too. In 2000, I was arrested for packing a pistol and wound up at Brooklyn Detention Complex, then known as Brooklyn House of Detention, one of New York City’s jails. At intake, a nurse asked if I used drugs, or if I had any psychiatric issues. I said no and no. She then asked if I had a family history of mental illness. I told her about my father, who’d left us when I was one, then committed suicide when I was ten. When Mom had told me, I’d felt betrayed. I’d felt angry. Until then, I’d always thought that one day he’d find me and explain himself. Instead, he took the coward’s way out.

I recounted all of this to the intake nurse, and I was put on suicide watch. Here’s how I remember it: While the others in custody headed to the main unit, I was escorted to another cell, with plexiglass on the bars, and given a smock to wear. After a couple of hours, I started spiraling. I flipped out and flailed my arms, and I demanded to see a psychiatrist. I was cold, the lights never went out, and nobody told me anything. A guard stared at me as if watching laundry on spin cycle: tumble, stop, start again. I was released twenty-four later. It remains one of my worst days in lock up.

There’s a social hierarchy in prison, a pecking order. At the very, very bottom are the pedophiles and sexual predators, which is where Epstein would’ve wound up. But he managed to skip out on that. He managed to skip out on facing judgement in a court of law, and he skipped out on being forced to face his alleged victims. Just as my father’s suicide denied me the chance to demand an explanation, Epstein’s suicide allowed him to write his own last chapter. And though I understand how he was able pull it off, it’s a shame that he figured it out, too.

John J. Lennon is a contributing editor for Esquire.

You Might Also Like