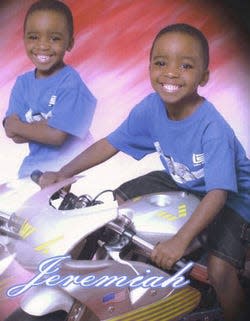

Jeremiah's story: The boy behind the 15th annual 'Walking for Change' events Saturday

The 15th annual Jeremiah Williams Domestic Violence Awareness Walk is Saturday at the Mount Moriah Missionary Baptist Church.

Since the 8-year-old boy was fatally shot in 2009, Mount Moriah Pastor Arthur L. Sample III and First Lady Barbara Sample have honored his memory with a 5K walk, information on community solutions to domestic violence, and tributes to Jeremiah, a nephew the Samples raised for several years before the state child welfare workers pushed his to return to a troubled home where he was fatally shot in an outburst of domestic violence.

The annual "Walking for Change" activities Saturday will begin with registration for the walk at 8 a.m., the program at 9 a.m. and the walk at 10 a.m. All events will be at the church, 2349 Keystone Way.

This story about Jeremiah's life and death was originally published Nov. 22, 2009.

Jeremiah Williams came into this world a child of poverty, surrounded by drugs, violence and despair.

His teenage father was shot to death six months before he was born. His young mother scraped by on public assistance while struggling with an abusive boyfriend.

But Jeremiah caught a break.

When he was still a toddler, Jeremiah's great-uncle, the Rev. Arthur Sample III and his wife, Barbara, took Jeremiah into their home, plucking him from his unstable life in the Phoenix housing project and delivering him to a suburban home where he found stability, privilege and love.

Through the years, the Samples bought him bicycles, electronic games and books. They took him fishing and to football games. They taught him to count and read. They set up a college fund.

For all intents and purposes, the Samples were the only parents Jeremiah ever knew.

The 8-year-old boy with the bright smile repaid that love and kindness — and made the most of his second chance. He was, by all accounts, a good kid — polite, caring and thriving in the Samples' care.

Then, on Feb. 9, everything changed with one phone call. It was Jeremiah's mother. She wanted him back.

The events that led to that phone call and what transpired over the next few months will forever haunt the pastor and his wife. What they are now left with, beyond the profound sadness of parents who lost a child, is a collection of "why" and "what if" questions — serious questions that yet again raise concern about the effectiveness of the public safety net designed to protect Hoosier children.

New life, out of harm's way

Arthur and Barbara Sample met Deneen Williams at the funeral of Jeremiah's father. Raphael Hendricks, who was a nephew of Arthur Sample's, was gunned down in a killing that remains unsolved.

After extending their condolences, the Samples offered their help to Williams, who was pregnant with Jeremiah and also had a daughter with Hendricks.

When Jeremiah was about 3 months old, in January 2001, Williams called the Samples. She was taking them up on their offer.

"Deneen said she heard Barbara loved children, and she asked if we could help her with Jeremiah," Arthur Sample recalled. "It started out with us taking him every weekend."

About a year later, Deneen Williams' mother called the Samples. Deneen Williams was in a volatile relationship with her boyfriend, Joshua Germany, and family members were concerned about Jeremiah's safety.

Jeremiah's grandmother wanted to know if the Samples would be willing to take Jeremiah permanently.

That night, Barbara Sample called Deneen Williams.

"She asked if she let Jeremiah come live with us, could she visit him," Arthur Sample said. "Barbara told her she could see him anytime."

Realizing the Samples could give her son what she couldn't, Williams signed a document designating the Samples as Jeremiah's guardians for medical and education purposes.

A few days later, Jeremiah was settled into his own room at the Samples' Northeastside home on a private lake. It was a world away from his life in the Phoenix apartments, the crime- and drug-plagued housing complex near 38th Street and Keystone Avenue where Williams lived.

After spending several months with the Samples, Williams contacted them and said she wanted Jeremiah back. He stayed with his mother a short while before she returned Jeremiah, then about 3, to the Samples.

This time, Williams told them, Germany had pulled a gun and made threats.

For the next six years, Jeremiah lived with the Samples, whom he called "Uncle Mane" and "Auntie Barbara." Williams visited occasionally — two or three times a year at the most, usually around holidays or on Jeremiah's birthday in October.

'They just adored him'

With their two children grown, the Samples had the time and means to dote on Jeremiah. Every year, they took him to Disney World in Florida — splurging on special packages that let Jeremiah dine with Mickey Mouse and other characters.

Jeremiah also was a fixture at Sample's church, Mount Moriah Missionary Baptist Church in Indianapolis, where he was baptized and showered with attention. His birthdays, the pastor said, were often an embarrassment of riches. Jeremiah would receive so many presents from family, friends and church members that they would set some aside, unopened, to give to less fortunate children.

"He was the perfect person for a present," Arthur Sample said. "Whatever he got, he was happy and acted like it was the greatest gift in the world."

When it was time for Jeremiah to start school, the Samples enrolled him in Andrew J. Brown Academy, an Indianapolis charter school. They also signed him up for additional help with reading, sending him to summer programs at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and arranging for private tutoring.

"When you saw Jeremiah with them, you almost forgot they weren't his biological parents," recalled Vonda Gee, a cousin of Arthur Sample's and close family friend. "You could tell by their faces when he was around that they just adored him."

It was no surprise, Gee said, because Jeremiah was a wonderful little boy.

Gee said Jeremiah had a gift for "making relationships with everyone he came in contact with." She says that might be a reflection of the boy emulating what he saw his "father" doing every week at church.

"It didn't matter if it was someone who was 70 or another child," Gee said, "Jeremiah would reach out and talk to them."

But he also was all-boy, enjoying superhero cartoons, bicycles, video games, fishing and, well, fish stories.

"He made up the most amazing stories about things like catching dinosaurs," Gee said. "He had a very vivid imagination, and I always thought he might make a good writer."

It was obvious, Gee said, that Jeremiah "was really flourishing with the Samples."

On several occasions, Arthur Sample said they approached Williams about adopting Jeremiah. But, he said, "She always said no."

Still, Jeremiah, by now 8, was leading a charmed, happy life. He was safe. Then came the phone call.

The Samples had just finished lunch when Williams called Feb. 9. She got to the point quickly. She wanted Jeremiah back and was going to pick him up that day.

The couple briefly considered defying Williams' request. But their arrangement with her was informal.

"We had no legal grounds to keep him," Arthur Sample explained.

The Samples, concerned for Jeremiah's safety, said their agonizing goodbye. And they were stunned: Why, after six years, did his mother suddenly want him back?

The answer to that question haunts the Samples to this day.

A record of violence

While Jeremiah thrived in a home filled with love, his mother's place — now an apartment at Hearts Landing, another low-income housing project near East 43rd Street and Post Road — remained in turmoil.

Germany, who was in and out of the home, was a man known for fits of violent rage, sometimes using his hands, and at least once with a gun.

Police responded at least 11 times to domestic disturbances — often violent fights — between Williams and Germany, dating to 2001, records show.

Germany was convicted in February 2003 of domestic battery. He repeatedly struck and kicked Williams then broke the telephone so she could not call for help during a fight over diapers.

Then, in 2007, Williams accused Germany of firing three shots outside her Heart's Landing apartment.

But police were not the only authorities involved with Williams and Germany. In December 2008, school officials alleged that one of the couple's sons had been abused and alerted the Department of Child Services.

The couple agreed to participate in an Informal Adjustment — a contract between the parents and DCS that acknowledged abuse or neglect and laid out steps they must follow to keep the state from taking their children.

At the end of December, DCS was contacted again, this time by the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department, after Jeremiah's sister, who was staying with a relative and did not want to return to her mother's care, alleged she had been abused by Williams.

It was around this time that a state caseworker unwittingly may have sealed Jeremiah's fate.

Williams would not comment for this story — and DCS, citing confidentiality rules, also would not provide specifics — but the Samples give this account:

During a home visit, a DCS caseworker asked about Jeremiah's whereabouts. More significantly, Arthur Sample says Williams told him the caseworker warned her that if she was going to collect welfare for her children then they needed to be living in the home.

"She told us the caseworker said that if she didn't go get Jeremiah back, they would take her other kids," Sample said, "and go after the (welfare benefits) she had received."

Thrust into another life

It's unclear if the caseworker knew Jeremiah was in a much better place. But what is clear, Sample said, is that was the reason Williams suddenly called to take back a son she had seen only a handful of times over the past six years.

Jeremiah, a little boy who seemed to be saved, would now be taken from a good home, the only home he really knew, and thrust back into his mother's world of poverty and violence.

After she retrieved Jeremiah, the Samples say Williams avoided them. They say she promised to keep him in the same school, but when Barbara Sample called the principal's office the next day, she was told Jeremiah was not there. Later, they learned Williams had enrolled Jeremiah in another school but in the wrong grade.

The Samples' one hope was that since DCS was involved, Williams and her children would be under close scrutiny. Still, the Samples were well aware of the domestic violence issues — and they didn't want to take chances.

Three days after Williams took Jeremiah, the Samples said they delivered a packet of information documenting their role in Jeremiah's life and concerns about his safety to a welfare worker who was assisting Williams with food stamps and other public benefits.

That agency, the Office of Family and Children, doesn't provide child protection services. The Samples didn't know that. But they said the worker promised to pass the information on to Williams' DCS caseworker.

At the time, Arthur Sample said, they did not realize that FSSA and DCS — two state agencies that both work with families and children — were not related.

Just two weeks after Jeremiah moved to his mom's home, DCS received a call from Riley Hospital for Children. One of Williams' sons got into some pills in the home.

A police report on the incident says IMPD and DCS both investigated. DCS officials, citing confidentiality rules, declined to comment, but The Indianapolis Star learned the investigation found no neglect in the case. So there was no additional action taken, although the DCS case begun in December remained open.

In the weeks after Williams took Jeremiah, the Samples tried to arrange visits or talk to him. But they say Williams always had an excuse. She would say Jeremiah was busy or outside playing or asleep and couldn't come to the phone.

Exasperated, Arthur Sample climbed into his SUV on May 1 and drove to Williams' apartment. She agreed to let him see Jeremiah.

"He was so excited to see me," Sample said. "I told him I was going to come back with his bicycles and games and clothes."

The Samples returned later that day, and Williams reluctantly agreed to let Jeremiah spend the night with them. Arthur Sample recalled how excited Jeremiah was to be back "home."

But it was short-lived. The boy had to be returned.

Tension in home grows

Police were called to Williams' apartment at least three times on reports of domestic disturbances in the months that followed.

On that third call, on July 18, police investigated a report that Germany choked Williams in front of two of her children. The report said the responding officer interviewed the children, and they confirmed Williams' story.

IMPD's domestic violence branch filed a report with DCS on the incident two days later, on July 20, according to Sgt. Paul Thompson.

By state law, DCS has a window of one hour to five days, depending on the level of threat detailed in a report, to start an investigation.

It's not clear what DCS did with that report, or the level of threat related by IMPD, but no immediate action was taken to remove the children from the home. DCS has a special domestic violence team in Marion County that has removed children from families where there was far less violence and turmoil. But the Informal Adjustment the couple entered into with DCS did not specifically address their long history of domestic violence, The Star has learned.

On July 22 — two days after IMPD sent its report to DCS — tensions between the couple spiked. Germany came to the apartment and confronted Williams as she talked with a male friend. After threatening the pair, Germany left. But he returned about 30 minutes later.

This time, police say, he had a shotgun.

As Germany approached a patio door, Jeremiah was sitting inside on the couch with his sister and two half-brothers — directly in line with the doorway.

"Oh my God . . .," Williams screamed as she saw the gun in Germany's hands. Her cry was interrupted by a shotgun blast that ripped through the screen door. Jeremiah was struck in the head.

Arthur Sample was conducting a weeknight church service when his cell phone, set to vibrate, went off several times. He wondered who would be calling but finished the service. Then he checked his messages. That's when he found out Jeremiah had been shot. Sample rushed to Riley. When he arrived, Jeremiah already was on life support. Sample tried to talk to him. But Jeremiah couldn't respond.

Jeremiah Williams was pronounced dead a few hours later. He was 8 years old.

The college fund the Samples set up for Jeremiah was used, instead, to pay for his funeral.

How did this happen?

In the months after Jeremiah's death, the Samples have been on a quest for answers to difficult questions. Most center on the actions — or lack thereof — of DCS.

Didn't DCS know about the ongoing domestic violence in Williams' home? What about the choking incident just four days before Jeremiah's death? And, if so, did the agency ignore it?

Did the worker from the Office of Family and Children pass along their concerns to DCS? If not, why didn't the worker explain to them that DCS was a separate agency and they needed to report their concerns there?

And did DCS know or even make any effort to find out about Jeremiah's life with the Samples — before apparently pushing his mother to move him back into poverty and violence?

"We put our trust in them," he said. "We kept him the better part of eight years, and he was happy. He was a wonderful child having a wonderful childhood. Then (DCS) took him . . . and he only lived five months."

Exactly what the agency's interaction with Germany and Williams involved is unclear. Again, DCS is prohibited from talking about specific details of its cases, said agency spokeswoman Ann Houseworth.

But Houseworth insists that the Samples' concerns never reached the agency.

Sample said the welfare worker who took that information back in February, however, called them after she learned Jeremiah had been killed and insisted she had passed the information along to DCS. When contacted by The Star, that worker referred questions to FSSA spokesman Marcus Barlow.

Barlow confirmed the agency did receive information from the Samples indicating Jeremiah had not lived with Williams for several years. But, he added, "as far as our records go, the Samples never reported to us the child was in danger."

"Someone dropped the ball," Arthur Sample said, "and no one seems to be willing to take responsibility for it.

"If we went to the wrong place, why take our information? Why didn't they just send us 10 blocks up the street to the DCS office?"

In their one and only meeting with DCS, last month, the Samples said they were told the agency was not even aware Jeremiah had lived with them.

It's possible Williams kept that information from DCS, Sample said, but he still cannot fathom why someone from the agency would not have spoken to Jeremiah and the other children about their home lives.

The DCS case involving Williams and Germany apparently was closed in June, just weeks before Jeremiah's death.

On paper, it appears as if the agency had done its job — the family's problems addressed, case closed, another positive statistic.

The reality was just the opposite. Jeremiah remained at risk in a highly volatile environment where serious domestic violence issues remained unresolved.

Dawn Robertson, spokeswoman for the family rights advocacy group Honk4Kids.com, said numerous red flags were missed or ignored in a case that appears to have been driven more by policy, money or a push to meet cookie-cutter deadlines rather than what's best for the children.

"Clearly, there were breakdowns," she said. "The bottom line is that this was a serious situation, and the 'inevitable' happened. DCS should have been able to foresee it."

DCS ultimately did take action. It opened a new case and removed Williams' other three children — after Jeremiah's death. Germany, who was charged with murder in Jeremiah's death, pleaded guilty in September to strangling Williams in the July 18 incident. He was sentenced to three years in prison and is awaiting a January murder trial.

Living with memories

When the Samples look back now, all they have are memories. Some are happy, some heartbreaking.

A video prepared for Jeremiah's funeral scrolls through dozens of photographs that recalled the good times, his years with the Samples documented by a seemingly ever-present smile. There was Jeremiah eating dinner with Mickey Mouse. Holding hands with Barbara Sample at church. Celebrating a birthday at Chuck E. Cheese. Sitting on Santa's lap. Riding a merry-go-round.

But one memory is forever etched on Arthur Sample's broken heart. It came during Jeremiah's last visit in May.

As Jeremiah prepared to go to bed for the night, he confided in the pastor. Jeremiah told him he was caught off-guard by the sudden move back to his mother's home in February. "I thought I was just going (there) to spend the night," Jeremiah told Sample. "I didn't know it was going to be forever."

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Jeremiah Williams killed after DCS moved him from stable home to chaos