Jerry Springer: From the mayor's office to tabloid TV, he led a showman's life

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Jerry Springer, the former Cincinnati mayor and councilman known around the world for his over-the-top tabloid TV show, died Thursday at his home in the Chicago area after a brief bout with cancer. He was 79.

Springer made a name for himself in the early 1970s when he landed a seat on Cincinnati City Council, but his many interests and considerable charisma took him well beyond local politics.

Jerry Springer dead: Maury Povich, Ohio politicians, others react to Jerry Springer's death

Springer's political career: Jerry Springer started in Democratic politics in 1968 and never gave them up

He was a showman at heart, his friends and colleagues said, and that was reflected often in a career that veered wildly from the serious to the absurd. He was the kind of guy who could run for mayor while also wrestling a bear on television to raise money for charity.

"When he walked into a room, people moved that way," said Charlie Luken, a friend and former Cincinnati mayor. "He made people laugh. He was so charming. In some ways, I was jealous of him. He made it seem so easy to be around people."

His popularity paid dividends in both politics and media. After a failed run for Ohio governor in 1982, Springer stepped away from politics and became a popular news anchor on WLWT-TV, where thousands watched him sign off every night with his signature line: “Take care of yourself, and each other.”

Connecting with people 'whether that was politics, broadcasting or just joking with people on the street'

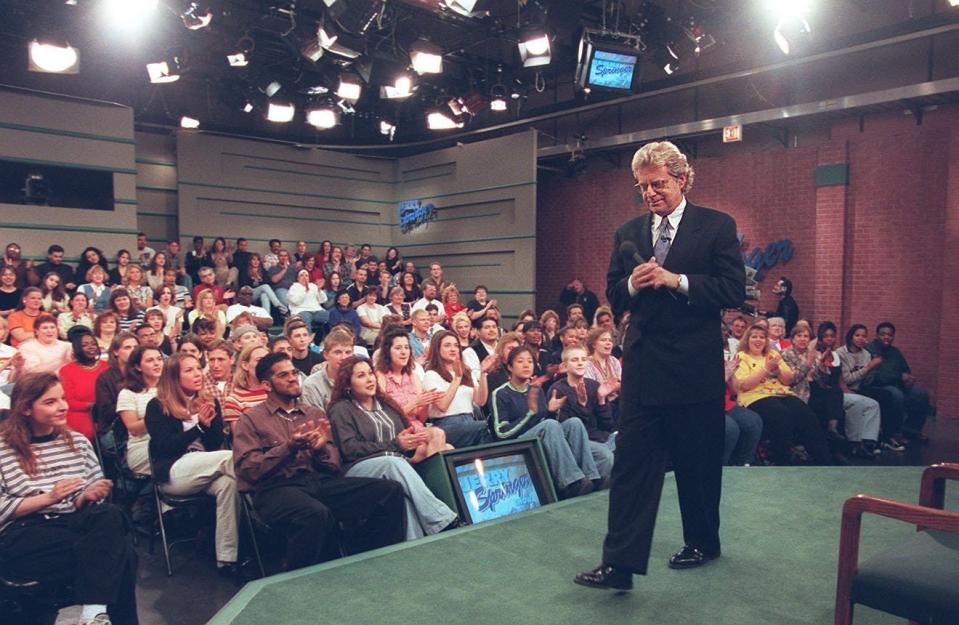

He later created a syndicated TV talk show, “The Jerry Springer Show,” which soon evolved, or devolved, into a raucous free-for-all featuring shouting matches, fistfights and broken furniture. The show became the standard bearer of a new brand of in-your-face television in the 1990s that audiences embraced and critics decried as exploitive and tasteless.

In the decades that followed, Springer wrote an autobiography, starred in a movie, “The Ringmaster,” about his talk show, and became a regular on “Dancing with the Stars.”

“Jerry’s ability to connect with people was at the heart of his success in everything he tried, whether that was politics, broadcasting or just joking with people on the street,” said Jene Galvin, a lifelong friend and spokesperson for Springer’s family.

“He’s irreplaceable and his loss hurts immensely,” Galvin said. “But memories of his intellect, heart and humor will live on.”

Starting in politics as a campaign aide in the 1960s

Springer, who was born in London and emigrated to New York with his family at age 4, served in the U.S. Army Reserves and graduated from Tulane University and Northwestern University Law School.

A legal career, though, was not in the cards. Springer quickly realized he had a way with people and a knack for politics. He got his start as a campaign aide in the late 1960s for Robert Kennedy, a job that helped shape his liberal politics and his personable manner on the campaign trail.

Tim Burke, former chair of Hamilton County's Democratic Party, got to know Springer when Burke was student body president at Xavier University and Springer was a young, activist lawyer. At the time, Springer led a campaign to lower the voting age from 21 to 19.

The measure failed statewide but won in Hamilton County. Burke credits Springer for winning many of those votes.

"He helped create excitement," Burke said. "Jerry was always terrifically articulate and could get up in front of virtually any crowd."

A career interrupted by a scandal

After winning a seat on City Council in the early 1970s, Springer brought his brand of showmanship to local politics. When the city took over local bus service in 1973, Springer "stole" a bus during a ceremony on Fountain Square and drove it around the block.

When he became concerned about the plight of inmates at the county jail, then known as "The Workhouse," he spent a night in jail with them.

"That was Jerry," Burke said. "Those were the kinds of things he did to make a point."

Despite his early success, Springer's career almost was derailed by scandal in 1974 when police learned the 30-year-old newlywed had paid a prostitute. He resigned from council when the news went public days later, citing "very personal family considerations."

He didn't stay away from the public eye for long. Just a few years later, in 1977, Cincinnati voters elected him mayor.

He campaigned at times with his wife, Micki Velton, with whom he had a daughter, Katie. The couple stayed together in the aftermath of the scandal but divorced in 1994.

Jerry Springer dies: How long was he mayor in Cincinnati? Did he still live here?

A mark made on Cincinnati

He remained on City Council through the early 1980s and made an unsuccessful run for the Democratic nomination for governor of Ohio in 1982.

Springer then became a staple on WLWT's evening newscast, which he co-anchored with Norma Rashid. Every night, he delivered a brief commentary on a national or local issue, ending each with his signature sign-off urging viewers to take care of one another.

The easy manner and charm that once helped him win elections turned out to be a hit on TV, too. "People tuned in to watch him," Luken said.

Former Cincinnati Mayor John Cranley was part of the generation of young Cincinnatians who grew up with Springer on their televisions every evening.

“There was a time when Jerry Springer’s nightly commentary was the moral voice of our region,” Cranley said. “I was raised listening to it. It always called us to our better angels and to care for the vulnerable.”

Rashid posted a photo Thursday of her and Springer on Facebook. "I am heartbroken," she wrote. "Love this man."

'The best kind of friend': Former WLWT anchor Norma Rashid remembers Jerry Springer

She said in an interview that Springer became as good a friend as he was a colleague. When she had a miscarriage, she said, he was among the first to visit her hospital room. "He was the best kind of friend you could have," Rashid said.

She said that connection resonated with viewers, especially in his nightly commentaries, which Rashid said he typed, poorly, just hours before the broadcast. Sometimes, she said, his lousy typing skills made it difficult for him to read his own words on the teleprompter, but he almost always got his point across.

"He was very insightful," Rashid said. "It was not just his opinion but a different way of looking at things."

David Pepper, the former Ohio Democratic Party chairman, said Springer's popularity was rooted in his sincerity and his sense of humor. He was a man who cared deeply about things, Pepper said, but he somehow managed not to take himself too seriously.

Whether or not they agreed with his politics, Pepper said, people were drawn to him.

"Everyday people of all stripes crowded around him as soon as they saw him," said Pepper, who attended political events with Springer over the past two decades. "He greeted every one of them like a new best friend, one hundred percent authentic and sincere."

Though well known in Cincinnati for years, Springer didn't gain national fame until he launched "The Jerry Springer Show" in 1991. The early episodes resembled an updated version of Phil Donahue's long-running talk show and ended with the same sign-off he'd used for years on WLWT.

That didn't last long, however. Springer soon embraced a show built on conflict, one that broke the rules of traditional daytime television and drew higher ratings than the early version of his show.

He aired episodes with titles like "I Married a Horse" and "Black Supremacists vs. White Supremacists." The interactions between the guests often were on par with those titles, with some engaging in shouting matches and others throwing punches, all while Springer looked on, befuddled or bemused.

"It was reprehensible, and even he acknowledged that," said former Ohio Gov. Ted Strickland, a longtime friend. "Even in the midst of that, he was never judgmental of other people. He felt that people should be able to live their lives."

In interviews, Springer sometimes came across as ambivalent about his show. He said he regarded it as entertainment, a distraction, and suggested no one should view it as anything else. He made no apologies for the show or his role in it.

"I would never watch my show," Springer told Reuters in 2000. "This is just a silly show. I don't take it seriously. But when people argue about the show intellectually, then I'm prepared to answer about why I think it is OK to do it and why I think it's important that shows like that are on the air."

The show, which ran for about 5,000 episodes over 27 seasons, went off the air in 2018. But Springer remained in the public eye, appearing on "Dancing with the Stars," on radio shows and podcasts, and even dabbling again in politics.

He raised money for Democratic candidates, became an outspoken critic of former President Donald Trump and attended the Democratic National Convention in 2016 to talk to Ohio Democrats and show his support for Hillary Clinton.

Jerry Springer dead at 79: Jerry Springer weighed in on Trump, Cincinnati politics in this 2020 podcast interview

In 2017, he considered a run for governor but decided against it. As in 2004, when he considered a run for Senate, some feared his baggage as host of his controversial talk show would hurt his chances, as well as those of other Democrats.

Those who knew him well said they'd remember Springer more for his friendship than for his politics or his show.

Rashid said they'd kept in touch over the years and always called one another on their birthdays. He called her in February for hers. She said they spent some time catching up and, of course, joking around.

"He wasn't your typical Cincinnatian," she said. "He was the wild card in every deck. He was unapologetically himself."

Reporters Cameron Knight, Scott Wartman and Laura A. Bischoff contributed to this report.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Jerry Springer obituary: From mayor to tabloid TV, he was a showman