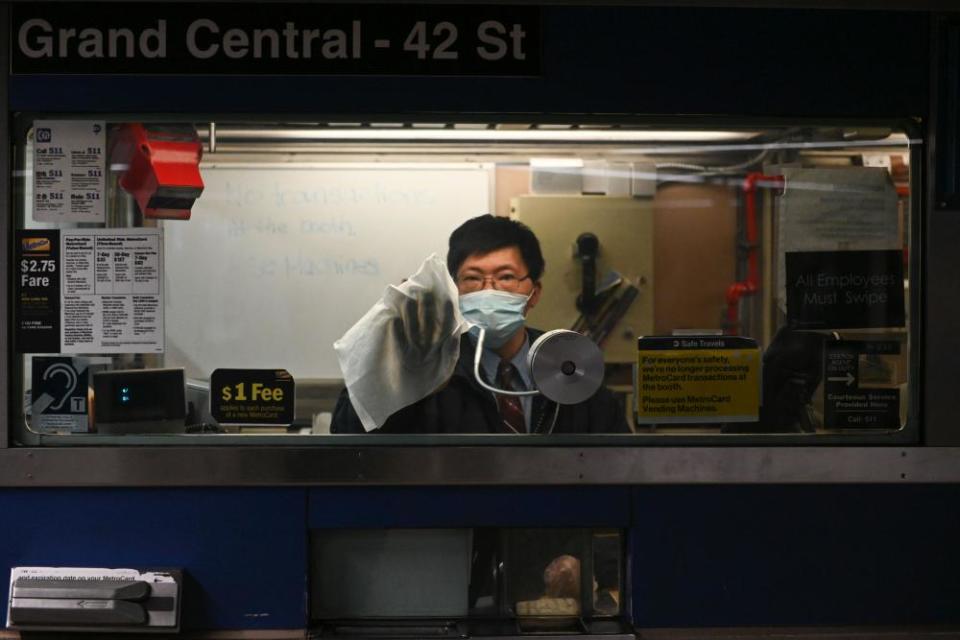

'I don't want this job to kill me': why have 68 New York transit workers died during the pandemic?

New York’s transit system is in crisis. Riders have disappeared as the coronavirus pandemic has locked down the city, funds are drying up. And for the 50,000-plus people employed by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), just turning up for work has become a matter of life or death.

So far about 2,400 transit workers have tested positive for the coronavirus while 4,000 are quarantined. Sixty-eight workers have died.

Related: Revealed: nearly 100 US transit workers have died of Covid-19 amid lack of basic protections

Many are angry at the way – especially in the early days – that the US’s largest transport system responded to the crisis. “They want to call us heroes now, but how can you call us heroes when you didn’t give your heroes the proper equipment to fight this?” said Tramell Thompson, a New York City train conductor.

Before the coronavirus brought New York to a shuddering halt the city’s overstretched and underresourced MTA was serving more than 5 million riders a day. Now 90% of those passengers have disappeared. But MTA staff have been designated essential workers – transporting doctors and nurses as well as other essential workers through the US’s hardest-hit city.

With workers off sick and trains and buses canceled, platforms are sometimes still crowded and trains packed even though ridership has plummeted. The transit system now faces an $8.5bn funding crisis.

Some are angry that the MTA did not move more quickly to protect them. On 4 March, according to documents seen by the Guardian, a note from an MTA official to transit staff instructed them not to wear masks because “since a mask is not part of the authorized uniform and not medically recommended at this time they may not be worn by uniformed MTA employees”.

On 6 March, another memo advised supervisors to tell transit workers wearing masks that they should not wear them during working hours.

Both notes said this order would change if the guidance changed – as it did – but for some MTA workers it was too little too late.

Thompson, a train operator for six years, tested positive for coronavirus on 13 April after quarantining from work. He first started experiencing symptoms when his asthma medication stopped working, and wasn’t tested until his symptoms worsened to fever, diarrhea and loss of appetite. “This job got me sick. No one else in my family is sick. I’m not going back to the job for it to kill me,” said Thompson. “I’m not going back to work until I’m able to breathe without any help.”

Michael Brantley, 36, another MTA train operator, spent three nights in the hospital earlier this month after testing positive for coronavirus. “I undoubtedly believe I got it from work,” said Brantley. “The MTA did not handle this well.”

“They have no problem playing Russian roulette with our lives,” said John Ferretti, a MTA subway operator and Transport Workers Union shop steward.

They waited until multiple workers died to start taking it seriously. We were sacrificial lambs

Canella Gomez, MTA subway operator

Transit workers also accused the MTA of not rolling out safety protocols quickly enough to protect workers and the public earlier from exposure to the coronavirus. The MTA was following state and federal guidelines. It wasn’t until 15 April that New York’s governor, Andrew Cuomo, told people to wear masks or face coverings in public whenever social distancing was not possible.

But MTA workers argue the transportation authority should have known what was coming. “They didn’t start taking personal protective equipment seriously until March 30. The first transit worker died on March 27. They waited until multiple workers died to start taking it seriously. We were sacrificial lambs,” said Canella Gomez, an MTA subway operator for eight years.

Gomez claimed a supervisor told him last month to talk to his union in response to requests to improve social distancing at the Bedford Park subway terminal in the Bronx. He also criticized the MTA for only providing temperature checks to supervisors in the subway division.

“It’s a slap in the face to every member of my department who is not sick, still coming to work to try to make their broken system work,” added Gomez.

Seth Rosenberg, a MTA subway operator, also noted he was told by a supervisor to talk to his union over concerns he expressed on 17 March about operating equipment not being sanitized and cleaned every round trip in between different co-workers using it.

“They told me it was my responsibility, not the MTA’s responsibility, and if I had safety concerns I should talk to the union,” said Rosenberg. “Our labor has been considered essential. Our health has been considered negotiable and our lives are considered expendable.”

Ray Reigadas, a MTA train operator, recently returned to work after being quarantined with coronavirus symptoms. He claimed the personal protective equipment (PPE) now being distributed to workers is rationed and limited.

“They are now giving out PPE, but you have to ask the dispatcher for it. You think they would hand it to you when you walk in. They give you one mask, two wipes and say that has to last you the week,” he said.

Our labor has been considered essential. Our health has been considered negotiable

Seth Rosenberg, MTA subway operator

A spokesperson for MTA declined to comment on individual complaints, but noted the agency had followed guidelines and advice from federal and state agencies throughout the pandemic and that transport officials too were frustrated by the lack of support they had received from the federal government.

“The guidance from the experts, the medical community, the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention], was specific that we should absolutely not distribute the masks and personal protective equipment we had stockpiled,” said Sarah Feinberg, MTA interim president. She noted the MTA decided a few days before CDC changed its guidance to distribute equipment anyway. She said MTA officials have been frustrated by the lack of support from federal authorities.

“We feel incredibly let down by the fact the federal authorities were specifically telling us not to distribute medical and personal protective equipment. I think it’s been frustrating for folks in my position and other positions that this guidance keeps shifting and it’s really hard to nail the federal government down on what the right response to any of this is,” said Feinberg.

Last week the MTA announced it would pay $500,000 each to the families of coronavirus victims, even if the MTA can not decisively trace the source of a worker’s infection to their job.

“What our frontline workers have done during this pandemic is nothing short of heroic and we believe this agreement is another crucial step in recognizing their sacrifice,” said Pat Foye, MTA chairman and chief executive, in a statement.