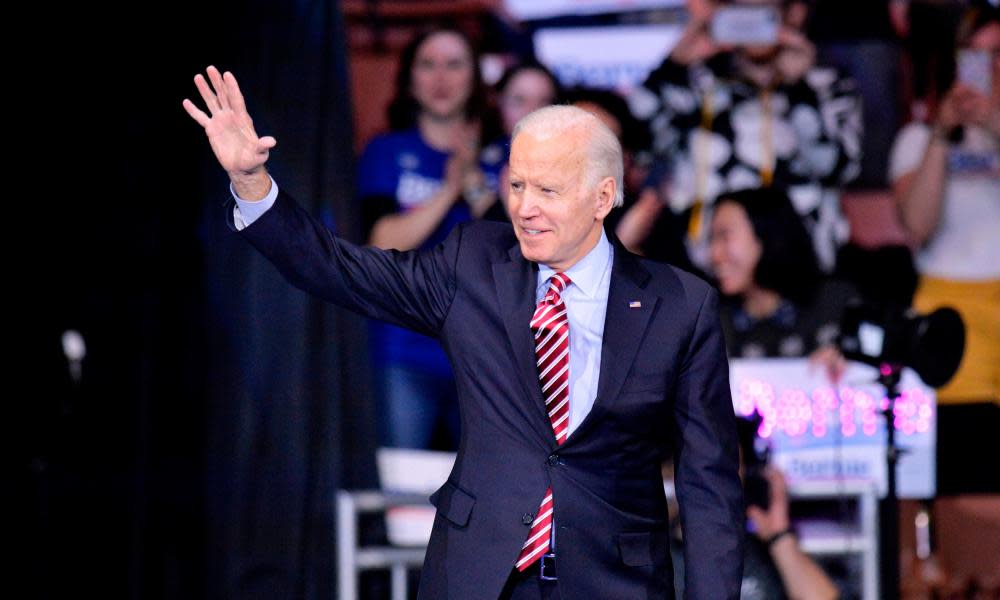

Joe Biden comes out swinging in New Hampshire – but is it too late?

There was a moment about five minutes into Joe Biden’s rally in Manchester, New Hampshire, that jolted members of the crowd up in their seats.

The former vice-president and Democratic presidential candidate, who has spent the past few months turning in soporific performances both on the debate stage and at his campaign events, became animated.

Related: Democrats step up attacks against each other as New Hampshire primary looms

Donald Trump was ruining America, Biden shouted into the microphone at the event on Saturday. He criticized the Vermont senator Bernie Sanders and former mayor Pete Buttigieg, who both claimed victory in Iowa and are running far ahead of him in the New Hampshire polls. This, at last, was the Biden his campaign talks about; the great campaigner, the king of the soapbox, coming out swinging.

It didn’t last long – moments later, Biden was struggling to remember the name of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal that he had touted as a key achievement of his time in office with Barack Obama – but at least it gave his supporters something to cling to.

They needed it, because bright spots have been few and far between for Biden of late. After the catastrophic performance in Iowa, where he finished a distant fourth, Biden is polling fifth in New Hampshire, too, unthinkable for someone who spent most of 2019 in the lead.

Perhaps it has, at last, jolted Biden into action. On Saturday, once he moved past the nuclear deal – the proper title is the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action – the former vice-president was back in his stride. After railing against Trump, he invoked his personal story.

“You know, I’ve lost a lot in my lifetime, like many of you have,” Biden told the crowd.

“A car accident took away my wife and daughter. Lost my son, Beau, like many of you have done. But I’ll be damned if I’m going to stand by and lose my country, too.”

The last line was delivered with a growl, and brought a roar of applause. This is a new part of Biden’s patter, and it went down so well that he used it again – and tweeted it – later that day.

For all the criticism of Biden personally, his lackluster performances don’t stand in isolation. There are things about his campaign, too, that just don’t quite work.

His slogan here, “Biden: works for New Hampshire”, scans as a shrug-of-the-shoulders acceptance, while on Biden’s yard signs the New Hampshire outline has been rendered in such a way that it looks like a raised middle finger. At events his staff display cardboard cutouts of Ray Ban-style sunglasses, in blue and red, a fun reference to Biden’s penchant for summer spectacles, but one that really had its day as a popular source of amusement back in 2014.

While the optics are awkward, there are signs, too, that the campaign has been guilty of resting on its laurels. In Iowa, where Biden struggled to turn out large crowds to his rallies, a campaign surrogate reassured the Washington Post ahead of the caucuses that people know Biden – they don’t need to come to events.

The primaries and caucuses are a series of contests, in all 50 US states plus Washington DC and outlying territories, by which each party selects its presidential nominee.

The goal for presidential candidates is to amass a majority of delegates, whose job it is to choose the nominee at the party’s national convention later in the year. In some states, delegates are awarded on a winner-take-all basis; other states split their delegates proportionally among top winners.

That analysis was wrong, clearly, and illustrated a gap in excitement between Biden’s supporters and those of his rivals – a gap which was on display on Saturday night, when Biden appeared with eight of the other candidates at the McIntyre-Shaheen 100 Club dinner in downtown Manchester.

The dinner is a litmus rest of enthusiasm in the Democratic party, and thousands of people had packed into the arena. Candidates’ supporters are assigned different sections of the arena, and Buttigieg’s crowd was the most visible, hundreds of yellow-clad acolytes sprawled across the far end of the arena, waving handed-out clackers and chanting: “President Pete.”

The Massachusetts senator Elizabeth Warren’s supporters, wearing light green, waving glowsticks and dancing to the Village People’s YMCA, occupied a broad swathe behind the speaker’s podium, next to a smaller but vocal mass of Sanders advocates, many waving neon pink “Bernie” signs.

Biden, by contrast, had lured out a tiny sliver of support. About 100 Bidenites were sitting in a little slice of the arena, boxed in on either side by Warren fans. Some of them had T-shirts, and several of them were holding signs that collectively spelt out “Biden 2020”, but as Biden, blood pumping with newfound vigor, jogged on to the stage, he would have struggled to pick them out.

“We’re being led by a president, a president, who actually has no empathy, no sympathy, who mocks people, who makes fun of people with disabilities, who does everything he can to demean. He doesn’t have a shred of decency in him,” Biden said.

“I’ll be damned if I’m gonna stand by and lose this election to this man.”

Biden’s performance wasn’t perfect – it might have been a good idea for him to take his hand out of his pocket, for one thing – but for those supporters who showed up it will have proved a nice fillip.

Most states hold primary elections, in which voters go to a polling place, mail in their ballots or otherwise vote remotely for a presidential nominee. These are much simpler than caucuses, which are hours-long meetings with multiple rounds of balloting.

The first caucuses took place in Iowa on 3 February. Donald Trump won the Republican contest by a landslide, but the Democratic vote ended in chaos, with Bernie Sanders and Pete Buttigieg both emerging as winners in a contest that was too close to call.

New Hampshire traditionally hosts the first primaries of the election year and has done so since 1920. All eyes will be on the competitive Democratic primary to see which candidate comes out on top. There will also be a Republican primary, though as Trump faces no serious competition, he is expected to win that contest by a huge margin.

The next morning, however, as Biden returned to action at a plush hotel in the seaside town of Hampton there were signs that he is still getting used to his new tub-thumping role. Biden spent the first 10 minutes wandering slowly about the stage, reminiscing about interactions he had with political figures in the 1970s, before new Biden took over, raising his voice and laying into Trump.

The change was marked enough that it caught out Biden’s sound man, and the microphone began popping.

Related: Pizza, sushi, Ben & Jerry's: what 2020 Democrats are feeding their staffers

“I understand the criticism, because we are a really almost like a visual audience these days,” said Paula Kougeas, 67. She was wearing a Biden T-shirt that she had purchased on the day he announced he was running for president.

“But you know, what we have is a really fast-talking, TV-ready slick guy in the White House right now, and that’s exactly what we don’t need in a president.”

When Biden announced his third presidential campaign, in April 2019, some wondered if he had left it too late in life. He first ran for president in 1987, and at 77 years old, after five decades in public office, he has visibly slowed.

While Iowa traditionally holds the first caucuses in the presidential election, New Hampshire has held the first primary since 1920.

The goal for presidential candidates is to win early-voting states and create name recognition and a sense of momentum, as well to pick up their first delegates, who will eventually choose the nominee in summer.

Sometimes a clear favorite for the nomination emerges quickly, but the last two major Democratic primary contests, pitting Barack Obama against Hillary Clinton and then Bernie Sanders against Clinton, have lasted from the Iowa caucuses in January through to late spring.

There is a video on C-Span, the non-profit which televises the process of US government, of Biden campaigning in 1987, during his run for president. His hairline – improbably – and bright smile are the same, but as a public speaker he is unrecognisable. The younger Biden speaks clearly and confidently, with a quicker cadence. He seems to be enjoying himself.

This is the Biden people think of when they talk about him as a great campaigner, and this week, in New Hampshire, crowds have seen a version of Biden that feels far closer to the 87 version than what his supporters witnessed in Iowa.

Perhaps Biden, after his months of stagnation, and brutal Iowa wake-up call, has finally been shaken into life. He might be able to keep up his newfound fire, recapture some of his late-1980s vigor, and turn things around in New Hampshire, and beyond.

Or, maybe, Biden has left it too late in more ways than one.