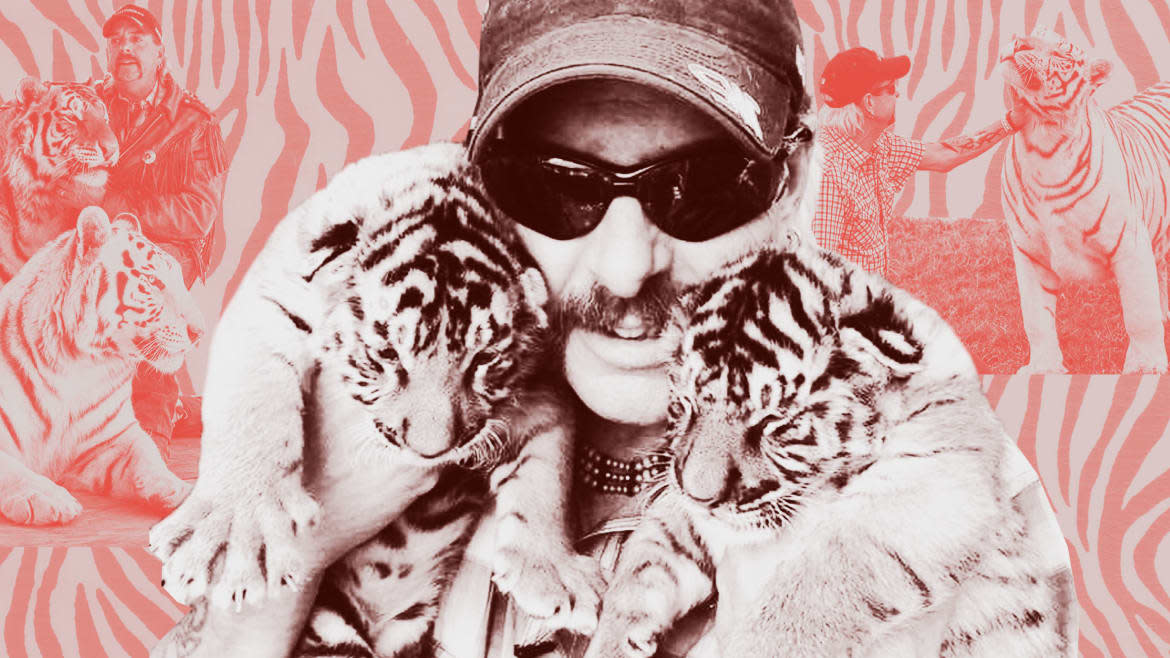

Joe Exotic Built a Wild Animal Kingdom. He Was the Most Dangerous Predator of Them All.

Joe Exotic said kill her and do it soon.

The “gay, gun-toting cowboy with a mullet,” as he liked to call himself, stood on the front porch of his Oklahoma zoo around midnight, speaking to the man he’d decided would kill his arch-rival. He proposed $5,000 upfront and a few thousand more after the deed, to be financed by selling off a rare lion-tiger hybrid—not a difficult task for North America’s most notorious big-cat breeder.

It was October 2017 and Joe was desperate. The animal kingdom he’d created over two decades, home to one of the world’s largest collections of big cats, now belonged to a belligerent former business partner. His White House run ended in comic failure. Critics and animal welfare groups claimed Joe ran a shabby “roadside zoo” of daily abuse, cruelty, and illegal trafficking.

Carole Baskin, a big cat sanctuary-owner from Tampa, Florida, had won a million-dollar lawsuit against him. She hunted his wealth ever since, and hounded him online. With her dead, Joe might focus on rebuilding the zoo, and his life.

The ribald man on his porch seemed as good a bet as any to bury her.

Allen Glover worked at the zoo after spending years behind bars for a string of attacks beginning at 17. He resembled Steve Austin, the professional wrestler, and Joe assumed the teardrop tattoo beneath Glover’s eye meant he’d killed before. Joe told him that Carole liked to walk to work along a leafy path and offered Glover hunting camouflage. Glover suggested cutting her head off with a knife. Joe liked the idea.

The hit was on, but Carole is still alive.

Now Joe is behind bars, awaiting sentencing for a litany of crimes that shattered his cuddly public image.

“A lot of people don’t know the truth,” said John Finlay, who had an 11-year relationship with Joe. “And a lot of people don’t care to know the truth… they want the nice story about the guy with the tigers.”

Joe controlled and abused the zoo’s staff, accused them of being traitors and threatened to throw them back on the streets. He hooked some on drugs. All of them witnessed animal abuse on an astonishing scale. Many felt they could never leave. Some who did said they’d escaped a cult.

Media lapped up Joe’s lies—a drunk driver killed his brother, he rescued a meth addict who became his husband—keen to buy into his quirky, animal-loving character.

The truth is far, far darker.

Joseph Schreibvogel was born in Garden City, Kansas, in 1963 to Francis and Shirley, devout German farmers who hauled their kids to Catholic church each Sunday. Francis was a spindly Korean War vet who smoked heavily and spoke little of war. Shirley, short and round-faced, had a softer side. She doted on her youngest son. He won school-fair awards in horses, poultry, rabbits and crops. But he often shirked the farm tasks foisted on his siblings Tamara, Pamela, Yarri, and Garold Wayne, known by most as “G.W.”

Joe escaped into fantasy worlds. He wandered about shooting animals with BB guns, then he injected them with water-filled syringes to “heal” them. He turned Pamela’s playhouse into a “vet center.” When the family moved to Texas, he worked at a local nursing home. He wore full scrubs, with a fanny pack and stethoscope. On breaks he told convenience-store clerks he’d emerged from successful surgery. During a stint in Wyoming, Joe hitched a flashing light to his old Buick and pretended to be a cop.

Joe spent three years beginning in 1983 as a cop for real, patrolling in nearby Eastvale, a languid, quarter-mile-long Dallas suburb. That year Yarri outed Joe as gay to his father, who made Joe shake his hand, and promise not to attend his funeral. Soon after, a devastated Joe drove his squad car off a bridge in an apparent suicide attempt. He spent 56 days in traction in Florida before working at a West Palm Beach store named Pet Circus.

By Joe’s return to Texas, in 1986, he had adopted his latest persona: a cowboy, complete with ten-gallon hat and sidestrapped six-shooter. He grew his hair into a mullet, dyed it blond, and began covering his wiry frame in tattoos. He worked security at the Round-Up Saloon, a popular gay bar in downtown Dallas. Sometimes he performed in drag as Dolly Parton. He wore spurs on his boots, even when shopping for groceries. One day, when visiting family, he wore them on the wrong shoes.

That year Joe met Brian Rhyne, a cosmology student at UT Dallas, and fell deeply in love. Same-sex marriage was decades away, but Joe and Brian soon wed anyway, in an unofficial ceremony. In 1989 they bought a pet store called Pet Safari, in Arlington, with G.W., with whom Joe shared a love of animals.

Brian was more reserved than Joe, and kept his husband’s hot-headedness in check. Garold dumpster-dove for Pet Safari’s materials and welded cages. Brian kept the books, and Joe was the store’s enigmatic, gun-toting face. He was a smooth talker, and a great salesman. Joe took a $50,000 loan from Garold and bought a new site, called it Super Pet, and added a lawn, garden center, 30,000-square-foot dog obedience training area, wildlife rescue center, and a petting zoo. It was the largest such venue in the state, Joe told people. Super Pet thrived despite complaints about dirty cages. It was a sign of things to come.

Garold married, had two kids, and coached soccer in nearby Ardmore, Oklahoma. Brian and Joe built a home in Fort Worth and traveled. “We worked together, lived together: the whole nine yards,” Joe told me. Around 1995 Joe and Brian traveled to Palm Springs, California. The pair thumped along the Coachella Valley dunes in a Jeep. Soon after returning, Brian got ill. Doctors diagnosed him with a life-threatening, HIV-accelerated fungal infection.

Then, on Oct. 7 1997, Garold was driving in rain near Dallas with Tamara, when a semi truck hydroplaned and crushed him in his chassis. A week after he was airlifted to a hospital, the family took Garold off life support (Joe claims he pulled the switch; others deny it).

The family won a $140,000 settlement from the trucking company whose driver caused the wreck—nobody was drunk behind the wheel, as Joe repeatedly claims. They agreed that some of the money from the payout would go toward a new soccer field near G.W.’s home.

According to the family, Joe then manipulated his parents with tales of Garold’s love for animals. He persuaded Francis and Shirley to ditch their plans for the soccer field, and spend the settlement instead on land for an animal park in their dead son’s name.

“He’s a goddamn, what do you call it, a Charles Manson,” Yarri told me. “They were still grieving, still grabbing at anything. He’s just got a way of brainwashing them.”

Francis, Shirley, and Joe settled on an 11-acre plot outside Wynnewood (pronounced “Winnie-wood”), a one-stoplight town of 2,000 people off I-35, around an hour south of Oklahoma City. Joe opened the G.W. Exotic Animal Memorial Park, named after his late brother, in 1999. The meandering Washita River separated it from the town. Joe tried moving Garold’s gravesite there, but his wife and children refused. They have barely spoken to the Schreibvogels since.

Joe opened with nine cages, a deer, and a mountain lion. The park began to fill almost immediately. Owners dropped lions, tigers, monkeys, birds, and other rare creatures at its gates. Brian looked after the finances, as he had done in Texas. It was the animal kingdom Joe had sought in Arlington. He told visitors Garold dreamt of seeing exotic animals in Africa–something his siblings deny.

“Joe used [Garold] and his memory to just get what he wanted,” Pamela told me.

Then came the emus.

Kuo Wei Lee, a Plano real-estate developer, bought dozens of the birds in 1995 when marketers promised riches from their lean meat and oil—a sort of red-meat alternative à la pork. By 1999 the craze waned, and Lee thinned his flock’s feed to save money. That February, cops raided his ranch in Red Oak, south of Dallas, and discovered 69 dead emus. An additional 100-200 birds were feeding on the remains. Officers called Joe and an associate to wrangle the surviving emus. Joe planned to keep some at Wynnewood.

The two-day operation was bedlam. Birds trampled other birds to death. Having saved over a hundred, Joe and his associate, tired, approached several more slowly, then fired at them with shotguns. They killed six. Some dropped instantly. Others, according to local reports, “flopped and jumped, requiring several shots.” Joe claimed he’d begun killing to prevent emus dying of stress. “We’re hurt, and we’re tired, and now we’re responsible,” he said.

“You can’t do something like that and explain it away,” said Red Oak Police Chief Doug McHam. “Nobody is that silver-tongued.”

McHam was wrong. A grand jury convened but refused to indict Joe and his associate, and the men walked free. Joe sued the SPCA of Texas, an animal welfare group, for releasing a video of the incident that he claimed hurt sales at Super Pet.

Fresh from Joe’s emu-killing exploits, the G.W. Park expanded rapidly. Joe sold Super Pet, and plowed its proceeds into Wynnewood. He was an expert speaker, and thrilled crowds during un-PC, curse-laden tours of the park. “This ain’t SeaWorld,” he liked to say, with a cheeky grin. His father Francis helped dig ponds and fences, and his mother Shirley did the shopping. Brian balanced the books. He and Joe didn’t kiss in front of Francis and Shirley. Instead they’d gently brush past each other’s arms.

Joe’s relationship with Wynnewood began well, too. He sat on the local chamber of commerce and volunteered as an EMT. Sometimes he snuck tiger cubs into the local hospital to entertain patients.

By 2001, Joe had 89 big cats and 1,100 other exotics, and the park drew healthy crowds. But Brian’s health worsened. His weight plummeted. A hospice nurse came by each day, and Joe became Brian’s primary carer. By mid-December, Brian was skeletal, and couldn’t speak. He died four days before Christmas.

Joe held a funeral at the zoo and named its alligator nursery as Brian’s memorial. He was relieved the pain was over. But having lost Garold four years earlier, he told me, “you tend to wonder what the hell you did wrong.” He thought the world had turned against him.

“When Brian died, that’s when [Joe’s] whole demeanor of everything changed,” Chealsi Putnam, Joe’s niece, told me. “Something just came over him and he was never the same again… as far as the way he even did business.”

Within a year, Joe hooked up with a hard-drinking, drug-using 24-year-old events producer named Jeffrey Charles “J.C.” Hartpence. Joe used J.C.’s equipment to take his animal show on the road. Inspired by David Copperfield, he donned sequined cowboy shirts and toured as an “illusionist” at malls and fairs across the country. Kids could pet tiger cubs for a fee. They “monkey promised”—on an actual monkey’s pinky finger—that they’d steer clear of alcohol and drugs, a lesson into which Joe folded his fake story about Garold’s drunk driver. He claimed abstinence himself, and toyed with several stage names before settling on “Joe Exotic,” traveling the Midwest in a truck loaded with baby animals. Public officials accused him of safety violations—Joe often left kids in cages with animals—but a combination of sharp wit and litigiousness shut them up.

Joe was also getting rich, and becoming a local celebrity. In August 2001 he rescued three emaciated bears seized from a Russian circus trainer. The Oklahoman prompted readers to donate $17,400 toward the bears’ upkeep. It encouraged Joe to reach out for more donations, and ask visitors to sponsor animals. Soon the park was festooned with memorial plaques and posters begging for cash. Being a tiger king raked in serious royalties. Some questioned where the money went.

“It was like a con deal from the start,” Yarri told me. “I think he started right then, like, ‘Dude, this is easy. I can eat Red Lobster every damn day, twice a day, and somebody else is gonna pay for it.’”

Joe boosted profits by breeding and trading exotics. He allowed customers to pet big-cat and bear cubs for a fee. “Everyone knew him as the person to buy and sell animals,” James Garretson, an early friend of Joe’s, told me. “He would breed anything he could get his hands on.”

Joe became adept at breeding hybrid big cats at Wynnewood, such as ligers (the offspring of a male lion and female tiger), liligers (second-generation male lion and ligress offspring) or tiligers (second-gen male tiger, ligress female)–animals that do not exist in the wild. (There are more tigers in American backyards than in the wild anywhere on earth, and wildlife trafficking is a $19 billion industry.) Hybrids could fetch many times more at sale than a regular cat. According to former crew members, Joe made between $1,500 and $10,000 for hybrid cubs, which many experts say are useless to the genetic diversity of big cats worldwide (many have inbred birth defects). Joe viewed himself as a creator of creatures; a demigod. He even told friends he wanted to reintroduce the saber-toothed tiger to America, an animal unrelated to modern cats, which died out around 10,000 years ago.

“He’s the spoke at the center of the wheel,” Brittany Peet, a counsel at PETA, told me. “There are others who breed, but he’s the primary one.”

Joe relied on a porous regulatory system that still does little to protect exotic animals in the United States. Laws are lax and authorities are stretched gossamer thin. The U.S. Department of Agriculture employs around 110 relevant inspectors for 10,000 locations countrywide.

There are around 2,400 zoos in the U.S., the vast majority of which are considered “roadside zoos” like Joe’s. The term is contested, but they’re generally private and unregulated, with little or no research function. Their conditions are poor even to untrained eyes.

Among the many roadside zoos I visited reporting this story, Joe’s old park was the worst. When I went, it had rained, and tigers sloshed back and forth in ankle-deep slurry. A man-made lake was neon green and stagnant. A brown bear sat in its own feces while a man fed it potato chips. Tenpins were scattered about the cages and one monkey enclosure featured a child’s kitchen play set.

The G.W. Park is one of around 80 U.S. facilities that allow cub-petting. According to USDA regulations, cubs may only be handled for a month-long period between eight and 12 weeks old. At many parks, cubs are caged, sold, or shot when they “time out.”

Joe found most of his staff through Craigslist. In 2003, a stocky 19-year-old named John Finlay answered an ad. He’d graduated high school in Davis, near Wynnewood, and wanted to be a carpenter. But jobs were scarce, and he didn’t hesitate when, one day after applying, Joe hired him. At first John mucked out cages and carried out other menial tasks with his misfit colleagues. But the tigers enchanted him.

John also thought his new boss was cool. Joe looked off-the-wall, like a comic book’s gunslinger and unlike anybody John had met in Oklahoma, or Texas, where he was born. Joe’s treatment of staff could be cruel bordering on vindictive—but John loved the animals. Joe took John to traveling shows in Kansas. The long trips gave them plenty of time to get to know each other.

John lived with a girlfriend in Pauls Valley, near the park. One night, a month after John began work at Wynnewood, he sent Joe a text message: “Come save me.” When Joe arrived, John’s girlfriend was throwing his belongings out onto the street. Joe drove John to the park. He wouldn’t leave for years.

Joe’s relationship with J.C. had already crumbled. The final straw arrived when J.C., drunk, held a gun to Joe’s head in their bedroom, Joe said. Police carted J.C. away, never to return. (He is serving a prison term in Kansas for murder and child molestation.)

John cut himself and suffered sleepless nights, and often lay in bed until mid-afternoon. He and Joe began a romantic relationship. They did almost everything together, as Joe had with Brian, and exchanged loving messages by phone. “I love that kid so much,” Joe told me recently.

John Finlay and Joe Exotic.

By 2004 the park was under the spotlight of authorities, who issued thousands of dollars’ worth of fines for illegal animal trading. Joe claimed the park swallowed $36,000 a month in food. David Steele, a bemused local cop, told a reporter: “I don’t know what his problem is. We didn’t force him to take the animals. He wanted them.”

PETA and the Humane Society also caught wind of Joe’s exploits. In a July 2004 Oklahoman article, Joe spoke out about giving sanctuary to a two-month-old crippled lion cub called Angel, against the advice of an Oklahoma USDA expert. In typically conspiratorial style, Joe warned that the government agency would “pull some strings out of the air to kill” the cat and frame him.

“I believe he’s breeding animals for financial gain,” one activist, a Tampa sanctuary owner then named Carole Lewis, was quoted as saying of Joe. “He’s the reason that poor cub was born crippled… People like that know what they’re doing.”

“If they have a problem with my morals,” Joe countered, “then they can write me a check so I can build separate cages for my males and females.”

It was the first public fight between Joe and Carole.

Big Cat Rescue sits at the end of a rough, tree-lined track off a busy street in suburban Tampa. It houses more than 80 cats whose large cages connect across 67 acres of rolling parkland. The walls of Carole’s office, located far from the sanctuary’s welcome center, are lined with pictures of big cats, and her 4x4’s license plate is CAT RESQ.

From the age of 9 or 10, Carole wanted to save cats, but refused to be a vet when she discovered they euthanized animals. She left home at 15, never finished high school, and paid for gas with pennies, for a $100 Impala she drove between three jobs. Eventually Carole settled on real estate, and made good money flipping delinquent Florida properties with a local magnate named Don Lewis, whom she married in 1991.

Carole never left her love of animals. She rescued bobcats from the age of 17, and used llamas to trim the lawns of new-buys. A year after they wed, Don and Carole visited an animal auction in Ohio to buy a pet bobcat. A bidder beside Carole said he planned to kill one on the way out, and stuff it. When Carole cried, Don outbid the man and they took the cat, Windsong, home. Soon afterward the couple rescued 56 more, and opened Wildlife on Easy Street, a big-cat bed-and-breakfast, where visitors paid $75 to spend the night with a predator. Within a year it held 200 cats from 17 different species.

Carole looked the part of big-cat hotelier, dressing from head to toe in tiger and leopard print, and exuding a kind of Grey Gardens mania in media interviews. She claimed the interactions at Easy Street would make visitors think twice about owning a big cat. “I thought, if people could go in a cage with one of those cats and see that they’re not affectionate—all they want to do is pee on you—that they won’t want them as pets,” she told me.

Rights groups called the hotel a roadside zoo. In 1997, Lewis, then 60, disappeared without a trace. His children suggested Carole may even have fed him to the tigers.

In 2000 the American Zoological Association, an industry body, refused accreditation for Wildlife on Easy Street. The internet meant people were posting pictures of their nights there. Carole grew concerned she was actually encouraging big cat ownership, and executed a volte face. She stopped visitors from touching the animals, and expanded cats’ cages. By 2003 Carole had banned all visitor interaction with the animals. Wildlife on Easy Street became Big Cat Rescue.

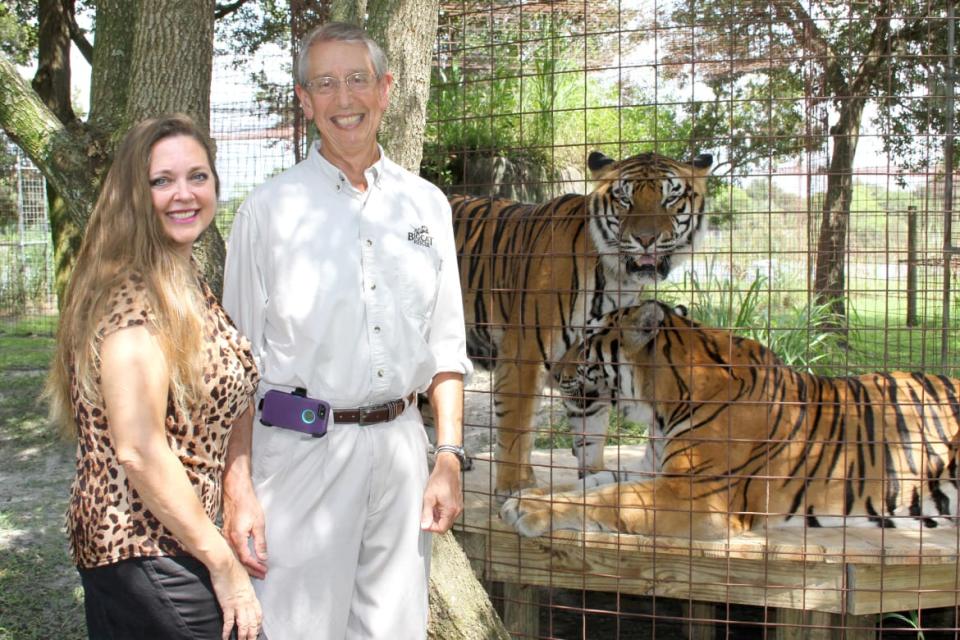

Around that time, Carole met Howard Baskin, a rawboned New York banking salaryman with a Jeff Goldblum-esque voice, on a blind date. He’d been to Wildlife on Easy Street in the ’90s, and the pair soon married. They advocated against private ownership of big cats alongside the Humane Society, PETA, and others. Carole encouraged her fans to report animal abuse. She launched the website 911AnimalAbuse.com and became a pied piper against roadside zoos, drawing fandom through daily video logs in which she still sported cat-print clothing. That earned her plenty of enemies. Howard, a law grad, helped deal with them behind-the-scenes.

“There is this thing that is bigger than all of us,” Carole told me when I visited, channeling her feline obsession, “and it’s personified [in the cats].”

Carole and Howard Baskin at Big Cat Rescue in Tampa, Florida.

Carole’s crusade against Joe and his cohort crescendoed slowly after 2004. Joe honed his roadshow and called it the “Mystical Magic of the Endangered.” John followed him almost everywhere. They attended animal auctions with other roadside zoo owners. The most notorious was in Ohio’s Amish country, where men in Brixton hats sold parrots, bobcats, and kangaroos as if they were old keepsakes. The state had some of the country’s weakest animal-welfare laws and a controversial roadside zoo of its own: Muskingum County Animal Farm in Zanesville, whose owner Terry Thompson enjoyed riding in his car with bears. Thompson’s zoo was a disaster waiting to happen, rights groups warned. He and Joe were friends.

In 2006 Joe published videos of Bonedigger, a 320-pound lion with brittle bones who shared his cage with a tiny wiener dog. Videos of the odd couple went viral. Joe used their fame to supercharge donations, which flooded in from all over the world. He needed them: Food for the park’s 200-or-so big cats could tally over half a million dollars yearly—not counting the other thousand animals.

Joe had a creative solution for that. At least twice a week he ordered staff out in a white delivery truck, with “NO PETA” written on its side, to gather expired meat and vegetables from Wal-Marts across Oklahoma. Sometimes the crew worked until 2 a.m. cutting food out of its packaging for use the following day. Oftentimes they ate the meat themselves: Joe joked it was a miracle nobody got sick. Other times crew killed and butchered the zoo’s “hoof stock”—low-value horses, cows, and goats—to be “fed out” to the exotics, his breadwinners. Some crew bid for horses at auction just to bring them back, kill them, and feed them out.

Authorities continued trying to crack down on the zoo. In 2006 the USDA suspended Joe’s exhibitor’s license and fined him $25,000 for failing to keep his cages clean or providing the animals with adequate medical care. PETA filmed an undercover video at the park that year, claiming staff kicked and hit animals with shovels and rifle butts. One manager was filmed saying he’d “beat the fuck” out of a white tiger, while another admitted he didn’t like Joe’s breeding process.

PETA called the G.W. Park a cub mill. Joe carped about PETA “spies” who infiltrated the park. He threatened those thinking of hopping the fence that he’d put a “cap in their ass.” But the claims Joe was churning out cub after cub were true; by 2006 the park officially made more than half a million dollars. Joe’s entrepreneurial instincts spawned branded T-shirts, cotton candy, bullwhips, skincare, underwear, wine, and even condoms. By this time, he referred to himself as the Tiger King. Later Joe added a watering hole called the Safari Bar, just off I-35, and a restaurant called Zooters (he had previously dreamt of calling it Tallywhackers—an all-male-staffed version of Hooters).

“It wasn’t G.W. Zoo,” one former employee told me. “It was the Joe show.”

Around the same time, Joe drifted away from Wynnewood itself. Joe and his staff drove his limousine into town for the odd meal at its lone Mexican restaurant. But mostly, the park became its own, insular world. Some townspeople were relieved their gay, gun-toting celebrity had retreated across the Washita. “The way he just expressed himself, you know, openly, like he was: I think he went against the grain around here,” Mark Lewis, editor of the Wynnewood Gazette, told me. “If he was in Las Vegas or something, I think he would’ve been just another guy on the Strip.”

But there was more darkness to Joe’s character than anybody in town imagined. The G.W. Park staff was a hodgepodge of homeless people, drug addicts, and others down on their luck. Some had arrest warrants in other states. Almost all were powerless, and lived in trailers at the park, working six days a week for as little as $150, with an extra $50-100 in cash, which Joe called “summer pay.”

Joe told me he wanted to give people a second chance: “I saw in my life what pushed a lot of people to drugs was being an outcast to society, so being gay I related to that.”

The truth, according to many staff with whom I’ve spoken, was that Joe was bent on control, abusive—sometimes physically—and sexually as predatory as the animals he loved to breed. Few believed they could leave. He could be kind one moment, and spiteful the next. Some of the more zoophile crew members took his abuse as collateral, knowing a regular park would never allow them so close to the animals.

Joe often posted ads on Craigslist for young men to join him and John for weekenders in Pauls Valley or Oklahoma City motels. They returned from the trips bleary-eyed and belligerent. Tiger, lion, and bear cubs lived in Joe and John’s trailer, and defecated everywhere. The smell was appalling. John blames Joe for introducing him to meth, and the pair began lifting weights. John took steroids, which swung his mood. “At the drop of a dime, I could go off,” he told me.

Joe bought John almost anything he wanted, from belt buckles to trucks. But he was possessive, and kept his young boyfriend high on drugs. “[Joe] had it in John’s head that if he left, he couldn’t go nowhere,” one of John’s former girlfriends told me. “He couldn’t do nothing.”

In 2009 Joe received alligators from Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch, upon the pop star’s death, and housed them in the building Brian had lived in at the depth of his illness. Somehow, the park was still growing. But it was the subject of eight separate legal cases that year. And Carole was turning her crosshairs directly on Joe.

She noticed he would use up to 20 company names for his roadshow to, as Joe put it, “keep Carole busy,” and switch if somebody detected anything untoward. Carole researched Joe’s tour schedule, and mobilized her followers to email complaints to venues. Sometimes Carole generated a thousand emails—a lot for a Midwest mall manager’s inbox. Most ignored them and let Joe continue. Some, though, canceled. Other times Carole would call up reporters where Joe was, and educate them about his abuse.

“It was having some effect and causing a problem for him,” Howard told me.

He was right. Joe accused crew members of being PETA spies, and kept them on the park after closing for long, rambling screeds that might last three hours. Around 2010 he sent John to scope out Big Cat Rescue, and sprinkled Carole’s name into daily conversation. Joe could barely wait to talk about the “bitch” who was after his business.

Animal abuse at the G.W. Park grew vaudevillian. Crew would stroll about tossing live chickens, cats, and other animals into big-cat enclosures, or shooting them for fun. Cats, gerbils, and rats were fed to snakes and big cats. Many animals went hungry for days; some starved to death. When a big cat got sick, Joe turned it into a donation drive, pleading online for money to heal them. One employee said she saw staff share a joint with a monkey, and that cubs were “routinely struck with force on the nose, face, eyes, and neck.” One crew member was dared to bite the head off a live snake—he did. Another said he witnessed Joe run over emus in a four-wheeler so he could sell their bones to the Museum of Osteology, in Oklahoma City.

Animals Joe and the crew killed were dumped in a spot toward the back of the park they called the “tiger pit.” The stench became so bad that Francis said it reminded him of the Korean War’s battlefields. He and Shirley still visited most days, but there’s nothing to suggest they conspired in the abuse carried out by their son, who was turning into something far more sinister than the fantasist he had been. Many crew members recalled Joe strung out, or acting like he was high on cocaine. Joe allegedly mocked disabled children who visited the park, and joked with one employee that a pocket knife was his “n---er stabber.”

“He started to lose grip on who he actually was,” John told me. “He’d joke about you to your face, or chat shit about you behind your back. He just was an all-round fucking asshole.”

On Oct. 18, 2011, Terry Thompson set 56 of his Zanesville animals free before shooting himself in the head. The ensuing animal massacre made headlines worldwide, as cops hunted Thompson’s deadly menagerie. Joe claimed activists murdered Thompson to tighten Ohio’s animal laws. At the time, 13 states allowed private citizens to own exotics, including Oklahoma.

In 2012 the Humane Society called the G.W. Park a “ticking time bomb, potentially 10 times worse than Zanesville.”

“If somebody thinks they’re going to walk in here and take my animals away,” Joe told a reporter, “it’s going to be a small Waco.”

Joe continued touring despite Carole’s efforts. Her email inbox filled with death and rape threats. One day she opened her mailbox to find it full of snakes. On another, somebody attached wires to make it seem like the mailbox was rigged with a bomb. A trapper attacked her in a parking lot after a court hearing. Joe denies he was behind the threats, though he did protest Big Cat Rescue dressed in a rabbit suit. “Carole is a fucking fruit cake,” he told me.

In 2011 Carole’s associates began emailing her about a mall petting act in which Big Cat Rescue was allegedly involved. She realized that Joe, in a stupid act of retaliation, had used her company’s name to promote his show. It was a legal open goal. Carole and Howard filed a copyright-infringement suit, but Joe didn’t back down. He countersued for libel and slander, demanding $15 million in damages.

Meanwhile, Joe had begun filming at the park, hoping footage would propel him to Hollywood. One night he addressed the camera, and said: “For Carole and all of her friends that are watching out there, if you think for one minute I was nuts before, I am the most dangerous exotic-animal owner on this planet right now. And before you bring me down, it is my belief that you will stop breathing.”

In 2013 a judge ordered Joe to pay Big Cat Rescue $1 million in damages. His attorneys dropped the $15 million suit. His relationship with John, who was hooked on meth and steroids, soured. John cheated on Joe with several women and told me Joe’s cult-like kingdom was crumbling, and that he resolved never to pay Carole a cent. He switched the park’s ownership, changed its name, filed for bankruptcy and hid assets. Carole hired investigators to find the cash. They pulled Joe’s siblings back into his orbit, and targeted a 235-acre plot of family land in Kansas: their inheritance. Joe’s legal skulduggery became King Lear with cowboy hats.

After Zanesville, Ohio passed some of the country’s toughest exotic-animal ownership laws. To prevent that outcome in Oklahoma, Joe needed national fame. He posted Craigslist ads for production staff to film reality shows at the park, hoping to become the next Steve Irwin, and hired musicians to write country songs he lip-synced in videos.

But he couldn’t shake his hatred of Carole. One of his songs, “Here Kitty Kitty,” featured a model feeding meat to tigers from a mannequin’s head—supposedly referencing Carole’s deceased husband—while Joe, dressed in shades, a pastor’s collar, and black hat, mimed lines like a spaghetti western preacher:

So if you’re ever down in Tampa on a big-cat refuge,

Don’t pick a fight with your wife,

‘Cause it’s a big 40 acres and if you’re not careful,

You’ll be gone in the blink of an eye

One of those asked to film Joe’s upcoming web show was Travis Maldonado, a handsome, six-foot-four-inch tall 20-year-old from Southern California. He loved bikes, and thought nothing of cycling 300 miles across the state on a $4,000 model his father Danny, a 23-year Marine veteran with a snow-white handlebar mustache, bought him. Travis had a roll-call of girlfriends and a job at American Tire that he’d gotten after ditching high school at 18. But he was bored, and experimented with drugs.

Travis and Danny saw Oklahoma as a chance to clean up and work on something fun. Travis wasn’t down-and-out, as Joe would later insist. The day he left, Danny handed him a thousand dollars to get to Wynnewood.

“He thought he was having the chance of a lifetime,” Sherry Peck, Danny’s girlfriend, told me. “He didn’t know he was walking into hell.”

As with John, Joe took an instant liking to Travis. He, Joe, and John continued to spend long weekends at motels, and invite other men into their relationship. Within a month of Travis’ arrival in October 2013, the three men wed in a ceremony at a hall across the street from the G.W. Park. Danny barely knew anything about the relationship. He didn’t even know his son was gay—not that it bothered him.

The big day itself, nine months before the first legal gay wedding would be held in Oklahoma, was an extravaganza Joe hoped would project him to the world. In a video posted to the JoeExoticTV YouTube channel, Joe invited a clothing store clerk to drop by. “It’s for a TV show,” he told her with a shrug.

Everything was zoo-themed. Monkeys carried flowers, the cake was tiger-striped, and a black Celebes crested macaque bore the rings. The three men wore bright pink cowboy shirts, standing in line beside a candle Joe lit for Garold. Joe stood in the middle, wearing a black, wide-brimmed hat.

Joe choreographed the day. Danny wasn’t invited. Joe didn’t want Cheryl there either. Only Travis’ older sisters, Ashley and Danielle, were asked to attend. “Joe said no and what Joe said, went,” Danny told me. I asked him why Joe kept him away.

“Control,” he said

Despite how contrived the ceremony felt, Travis seemed happy. Joe treated him like a big kid. He bought Travis a four-wheeler, gave him cash, and let him roam the park. Travis liked to shoot guns into the ground. He smoked a lot of pot. He could be mean, throwing live chickens into the cat cages. He also hit cubs. One staff member recalled him as “particularly sadistic.” Others liked him. “Travis was a blast, man,” former crew member Dianna Mazak told me. “He was loud and crazy and didn’t care.”

Joe continued to sell live and dead exotics off the books. He was a lynchpin in North America’s illegal animal trade. But as more animals arrived at the park, profits fell.

At the same time, Joe stepped up his online attacks against Carole. He posed with a rifle on Facebook, with the caption “Bring it on, bitch.” When Howard mentioned the threats at mediation once, Joe admitted he’d done it. Then, according to Howard, Joe waited until the two men were alone. “Nothing personal,” he said. “What could be more personal?” Howard told me.

On Feb. 17, 2014, Joe posted his most surreal and threatening video. “You wanna know why Carole Baskin better never ever ever see me face-to-face?” he asked, before shooting a blond-wigged doll live on camera. It was the first time Carole genuinely believed “that he would pay somebody. You could see him trying to whip people into a frenzy to kill me,” she told me.

Between his wild actions and the park’s unending abuse, most film staff left soon after they arrived, unable to package the horror they witnessed into a family-friendly product. Rick Kirkham, a former Inside Edition journalist whose crack-cocaine addiction was the subject of a 2006 documentary called TV Junkie, lasted 11 months. He witnessed the worst of his employer’s cultish behavior.

Joe shot into walls, and near employees, who ate the meat Joe pooled from Oklahoma Wal-Marts. If staff did anything wrong, Joe cut off their food. Joe controlled when crew members slept, when they got up, and forbade relations between them.

“We worked with animals that kill people,” Joe told me. “There was no room for grab-ass or kissing.”.

“They could not leave the park,” Rick told me. “They were totally in a trance-like state.”

Many people would only speak to me anonymously for this story. Some fear Joe’s power to harm them.

The trailers were dumps, and some employees slept on insect-covered floors. One time, Joe caught two crew members cavorting in a trailer. He frogmarched the young woman to the park gate and said, “Good luck, bitch.” Another employee named Saff lost her arm when a tiger mauled her through a cage. “She couldn’t follow rules,” Joe told me.

John’s steroid and meth addiction worsened throughout the year. He overdosed, and almost died. He often woke up in the middle of the night “ready for a fight,” Joe told me. In August 2014, John attacked Joe. Cops charged John with assault and battery.

Rick saw Joe shoot one tiger during his year at the park. Another day, an old lady brought a horse to the park and told Joe she couldn’t look after it any more. Joe hugged her and said he’d care for the creature. When she left, Joe told Rick to turn his camera on. Then he whipped out his gun, and shot the horse in the head while it was still standing in its trailer. “What the fuck,” Rick cried.

“I’m not a charity,” Joe replied. Then he fed the horse out to the lions.

Joe often griped to Rick about Carole: how she was mad and would never get his money. He fretted she’d get the park when Shirley died, and tried putting his share of its ownership in the names of others. It seemed like he was stalling for time.

When Rick told Joe he’d need to calm down for the cameras, Joe told him to fuck off. Another time in December 2014, Rick threatened to release footage of animal abuse. He threatened Joe: “I’m the guy that has video that could put your ass in jail and you know it, so don’t fuck with me.”

That night, Joe changed the locks on the studio, and announced he’d leave town for three days. Rick and the crew threw an impromptu party at the trailer. It had been a miserable 11 months, but they’d made it. The next morning around 7 a.m., Rick recalls, one of the park managers kicked in the door of his trailer.

“Grab your camera,” the manager yelled.

“Camera?” Rick replied. “The cameras are all in the studio.”

“There is no studio! The studio burned down overnight.”

The hut that was once Brian’s hospice was ashes. Michael Jackson’s alligators boiled alive in their tanks. Joe blamed Rick and Carole. Rick blamed Joe. Whatever the truth, Rick’s video was gone. He dropped to his knees, and cried.

Whether by accident or design, Joe’s hopes of becoming a reality-TV star were—temporarily, at least—over. And with his cash dwindling, and Carole closing in on the settlement, he was getting desperate for a break. Luckily, one was about to stroll right onto his property.

Like Joe, Jeff Lowe was no stranger to showbiz—or controversy. His grandfather founded a circus and worked with Ringling Brothers, and one of Lowe’s first high-profile jobs was managing daredevil motorcyclist Robbie Knievel, son of Evel (who has since called Lowe a “fraud,” “fake,” and a “loser”).

In the early 2000s Lowe ran a liquidation store in Beaufort, South Carolina, and spent no shortage of time in court. In 2007 he settled a lawsuit with Prince that accused him of selling clothes emblazoned with the artist’s trademarked symbol. A year later Lowe pleaded guilty to mail fraud, having posed as a domestic-abuse charity to get marked-down goods for his store. “He’s kind of talky, arrogant,” Joe Barth, who ran a drive-in theater opposite Lowe’s venue, told me. “He likes to brag.”

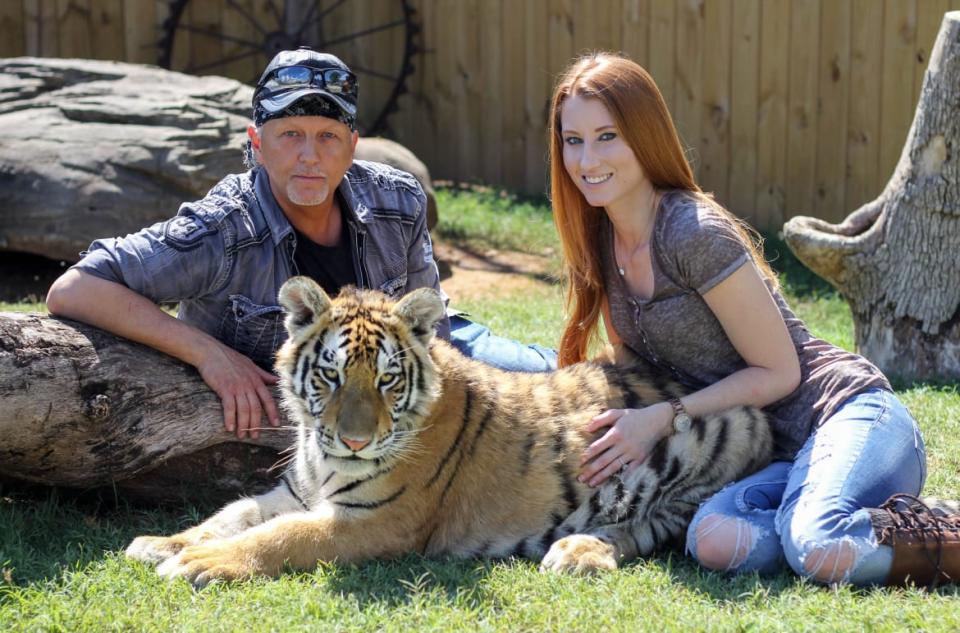

Lowe turned his Beaufort store into a roadside zoo filled with tigers. He met Lauren Dropla, a local many years his junior, in 2013. Hounded by city councilors concerned about the tigers, Lowe left South Carolina in 2015, and split from his wife Kathy soon after.

That year Lowe and Lauren visited the G.W. Park. They wanted a home for 12 big cats and sought a hybrid. They also wanted a zoo of their own, and flew Joe and Travis to their 12,000-square-foot home in Colorado. Lowe was short and stocky, with doughy eyes. He always wore a biker jacket and do-rag, under which locks of gray hair tumbled out like instant noodles. He accessorized his Ferrari sports car with a Ferrari-branded baseball cap. Lauren was slim and glamorous, with silken red hair.

Jeff and Lauren Lowe.

Some might have sniffed out trouble. Joe smelled success. He needed cash with Carole owed the $1 million from her lawsuit.

“He saw the Ferraris and the Porsches and all the exotic vehicles,” Lowe told me of Joe. “And I think he saw me as his meal ticket.”

Lowe also saw his houseguest as a chance to start anew. He told Joe to dissolve the G.W. Park’s LLC, open another in Lowe’s name, and continue running tours and shows as its “entertainment director.” Joe was out of food and hadn’t paid utilities: Lowe would keep the park alive. According to Lauren, he sweetened the deal with an additional $100,000. It seemed fair.

John was expecting his first child with a woman at the park when he and Joe broke up. Joe and Travis stuck together, however, and wed when Oklahoma legalized same-sex marriage. The trip to the Lowes’ home would be their honeymoon.

Within months, Lowe and Lauren were living at the G.W. Park. Lowe joined calls between Joe and Howard, and continued to breed and sell big cats. In June 2017 he opened Neon Jungle, a cub-petting storefront in a Oklahoma City mall, charging customers $25 to pet each animal. A month later he and Lauren wed at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas. Jeff wore a black do-rag.

The abdicant Tiger King, meanwhile, sought a new throne: the White House.

Joe called himself a libertarian; he was pro-choice, pro-LGBTQ rights, pro-gun and—naturally—pro-exotic-animal ownership. In a campaign video circulated worldwide, Joe, wearing a tasseled suede jacket, announced:

“I’m not cutting my hair. I’m not changing the way I dress: I refuse to wear a suit. I am gay. I’ve had two boyfriends most of my life. I currently got legally married. Thank God it’s finally legal in America. I’ve had some kinky sex. I’ve tried drugs through the younger years of my life. I’m broke as shit. I have a judgment against me from some bitch down there in Florida.”

Joe hired Josh Dial, a gun-store clerk in Pauls Valley, who once attacked a man with a ninja sword, as his campaign manager. Joe didn’t know the difference between Republicans, Democrats, and libertarians. “My job was to make him appealing to the libertarian crowd, even though he wasn’t a libertarian,” Josh told me. “I really just tried to drill as much as I could in him.”

Joe didn’t win the 2016 race (he became a Donald Trump fan). In 2017 he set his sights on the upcoming Oklahoma gubernatorial election. He again hired Josh, who moved into one of the park’s trailers. Joe coined the hashtag #FixThisShit. He spent park cash on condoms decorated with photos of him in a suggestive pose. In June 2017 he and Josh, who is also gay, visited the OKC Pride parade in Joe’s limo. Joe jumped on the car’s roof and waved to the crowd. They erupted. “That was probably the only time I thought, ‘Wow, this guy could actually do something,’” Josh told me.

Just when things looked up, a tragedy brought Joe’s life crashing down.

Around lunchtime on Oct. 7, a clear, sunny day, Josh and Travis sat in the park office. Travis toyed with a .45 Ruger pistol that Joe had bought him. He’d heard the weapon wouldn’t fire without its magazine. He racked its slide, held the barrel to his temple, and fired. A bullet went straight through Travis’ brain, slapping into the wall beside him. For a few seconds, Josh thought it was a prank.

“It looked like Hollywood shit, blood spurting out from everywhere,” he told me.

Travis’ head fell back. His Adam’s apple bobbed up and down faster than Josh had ever seen. Eric Cowie, a military veteran crew member, took the gun from his hand and wrapped Travis’ head in a white shirt to stem the bleeding. But Travis, 23, died minutes later. Josh went into shock. “I don’t think I’ll ever be the same person,” he told me.

Joe was in Pauls Valley. When he returned, he howled. It was 30 years to the day since Garold’s death.

The next morning, Joe stood before TV cameras, weeping in his pink wedding shirt. “One careless mistake snuffed him out,” he said. Days later John found Joe in his garage, with a cellphone in one hand and a gun in the other. He’d blasted a hole in the television beside him.

Danny only discovered his son’s death via Facebook. Joe told the family to stay away, and cremated Travis’ body four days later, before they arrived in Oklahoma for his funeral.

It was a bizarre affair. Joe wore the faux pastor’s outfit from his “Here Kitty Kitty” video, complete with hat and wraparound shades. Harley-Davidson bikers from nearby Moore accompanied the cortege into the G.W. Park. Hundreds attended. Joe stood at a lectern, flanked by friends, family, and former lovers. The sun cast a hazy penumbra across his black frame.

“I met Travis when he was basically homeless and had a backpack on his back,” Joe lied. He waxed about their relationship, and ended: “If we can pull one thing off with this horrible tragedy, it is to continue to bypass the hate and the judgment that we cast upon each other no matter what we do.”

Danny was furious. “He’s not an ordained priest,” he told me. “He’s such a fake. It’s all BS—everything. It’s all for publicity… the whole thing’s a circus.” Joe gave Travis’ family his ashes in Wal-Mart-bought containers. Danny had seen many ashes during his military service. They were gray. These were white. “I did not believe what he gave me was my son’s remains,” Danny told me. Joe denies the claim. “Danny needs to let his son rest in peace,” he told me.

Soon after the funeral, Joe set up the Travis Maldonado Foundation, a group whose website claims it provides “no-cost resources for those struggling with meth addiction and gun-safety education.” Donations go to the United States Zoological Association, a group Joe founded and led.

Just days later Joe was out on the park again. Five new tigers were arriving. To make room, Joe shot five older tigers—Cuddles, Delilah, Lauren, Samson, and Trinity—through the head with his shotgun. “If I knew it was this easy, I’d just blast them all,” he told Cowie.

Lowe feared the park would never make money. With Joe’s Wal-Mart scheme over, food cost a fortune. “There really isn’t much left here besides cats for people to look at,” he texted Joe. “The place just eats money.” Police arrested Safari Bar staff for dealing meth. Lowe planned a “Jungle Bus” mobile cub-petting zoo in Las Vegas.

That November, Joe appeared at a Libertarian gubernatorial event in Oklahoma City. He cussed and guessed the ethnicity of audience members. “It was going off the rails,” one political activist told me. Joe lost his primary. “His existence as an Oklahoman is more like a roadside attraction,” the activist continued. “Like, he’s the world's largest peanut, or whatever. I think people kind of view him as that. He’s the goofy part of Oklahoma. That’s what he represents: how silly we can be sometimes.”

Carole didn’t think Joe was silly. In February 2017, a G.W. Park employee named Ashley Webster left her a voicemail. Joe had asked Ashley to kill Carole, and she believed he was serious. “I felt like your life is in danger,” Webster said.

Webster’s voicemail was forwarded by the Baskins’ attorney to the FBI. There was already an investigation underway at the G.W. Park. Special Agent Matt Bryant, with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, was examining accusations of animal cruelty when he caught wind of a potential murder plot.

James Garretson had recently returned to Joe’s life: He wanted tips on opening a tiger B&B much like Wildlife on East Street. But he grew frustrated at the abuse he witnessed in Wynnewood. “He was doing some evil things down there with the animals,” he told me. Joe had asked him to kill Carole Baskin, too—it was becoming tougher to find people Joe hadn’t asked to murder his arch-rival. “When is she ever gonna fucking stop,” he asked Joe in September.

“She won’t until somebody shoots her,” Joe replied.

Lowe said Joe asked him to bring up Google Earth on his computer (“my monitor is huge”) Joe and Travis mapped out places to kill Carole. Jeff told me he suggested not to kill her but to “burn her shit to the ground.”

By the time Allen Glover, a recent staff addition, entered the fray to kill Carole, Joe was already under surveillance. Glover hated Joe, too. He was “an asshole,” Glover later testified. “Treat his employees like dirt… he would downgrade me to the point where it was coming close to blows, that’s how bad it got… he’s just—he’s really a cruel, cruel person.”

Joe thought Glover should travel to Big Cat Rescue with a fake ID. He ordered John to drive Glover to a Dallas lighting store to get one, and mailed his cellphone to a Las Vegas address registered to Lowe, to cover his tracks. But Glover decided to split with Joe’s money, and flew to Savannah. His teardrop tattoo was in fact a tribute to his late grandmother. Glover planned to warn Carole in person, but didn’t make it to Tampa before stopping at a beach and blowing all the money on partying.

Bryant, unaware of Glover’s whereabouts, warned Howard and Carole about an “imminent threat.” They bought window blinds, began carrying pistols, and avoided riding bicycles to work. People knew Carole in Tampa, and often stopped her in the street or supermarket. One time Carole was filling up at a gas station when a man approached her. She shuddered: Do I need to grab the gas and spray this guy?

Joe was out thousands of dollars, Allen Glover was gone, and Carole Baskin was still alive. Joe gave up on his deadly plot for a while. But on Dec. 8, Garretson brought a man named Mark to the park, and told Joe he could be trusted to kill Carole. This time Joe was in no mood for workarounds.

“Just follow her into a mall parking lot, cap her, and drive off,” he said.

By that time, Joe had found his latest beau, a young Austin man named Dillon Passage. Joe believed Travis had sent Dillon to the park keep him from committing suicide. The two applied for a marriage license in Pauls Valley 59 days after Travis’ death.

Lowe and Joe’s relationship, meanwhile, was in tatters. The park’s finances already hung by a thread, but Joe had siphoned park funds for his gubernatorial race, forging checks and spending cash on gifts for Dillon, such as a Ford Mustang. Text messages between the two men in 2018 devolved from bro-ey friendship to venomous hatred.

It boiled over in the park’s office.

“You commit more crimes than any of us combined, but you never get in trouble because you pass the buck on to someone else,” Lowe shouted at Joe, according to video taken by Lauren. Dillon was a “cheerleading faggot,” Lowe added. “He’s not even a man like you. He’s a sissy boy.”

Joe argued back feebly, but he was crestfallen, and physically broken. He’d run a stop sign driving to Francis, by then heavily ill with Alzheimer’s disease, and was hit by a truck. He broke bones in his back, neck, and right leg. He opened a dialogue with Britanny Peet from PETA, hoping to bring down Lowe and others. Joe told her Travis’ death had changed his perspective.

“He felt he was wasting his life,” Peet said. “He also felt that a lot of the people in the exotic-animal business that he had defended over the years had thrown him under the bus.”

Lowe wrote Joe out of the park’s ownership. He renamed it the “Greater Wynnewood Exotic Animal Park”, to keep the “G.W. Exotic Park” signs along I-35. Joe wanted out. He had spoken about fleeing to Belize with several people at the zoo. He sold some tiger cubs, packed a camel, and some dogs in a trailer, and drove to Yukon, just west of OKC, with Dillon. There he paid $2,000 rent to live on a 6-acre property.

It was real Oklahoma. Fracking towers and grain silos peppered the flat, blanched horizon. Joe had spent decades creating worlds to suit him. Now he was a blond-mulleted cowboy in the buckle of the Bible Belt. He and Dillon rarely left. Locals didn’t chat across the fence. “The other neighbors were upset there was a camel,” one told me. The couple texted love notes from different rooms so they would never be apart.

Meanwhile, threats arrived from Lowe. “Fuck with me and I will bulldoze your house off the property,” he texted Dillon.

One night in August, Joe and Dillon left suddenly. Joe posted a photo to Instagram with the hashtag #Belize. They were actually in Gulf Breeze, Florida. Joe washed dishes at a pirate-themed restaurant. On Sept. 7, he left their rented home, hoping to get a job at a nearby hospital. As Joe stepped out of his Ford F-150 on its lot, four cops surrounded him.

“Get on the ground!” They screamed. Joe’s new life had lasted just 81 days.

Mark wasn’t a hitman, as James Garretson had told Joe; he was an FBI agent. Garretson had agreed to wear a wire and recorded the entire plan to kill Carole. Joe never stumped up the cash for his second hitman—but it didn’t matter. Hours of damning footage was played to jurors at a weeklong trial in Oklahoma City this March.

Carole testified for one day, escorted to court by armed guard. She didn’t stick around for the verdict, fearing one of Joe’s followers would execute her, Jack Ruby-style.

The jury took just hours to convict Joe on 21 counts, including two of murder-for-hire, five for the tigers’ deaths, and more than a dozen counts of illegal animal trafficking and selling. Joe’s defense he was playing along to incriminate Lowe and the others fell flat, as was his insistence he was entrapped. The judge barred Joe from mentioning Don Lewis’ death during the trial.

“Here’s the thing with kings,” said Assistant U.S. Attorney Amanda Green. “They start to believe they’re above the law.”

Sentencing is expected next month. Joe faces 20-plus years in prison.

When Carole returned to Florida, she posted a video saying that Joe was not simply “one crazy bad apple,” and called out several other roadside zoo owners. She still updates 911AnimalAbuse.com. When I visited Big Cat Rescue just after the verdict, Carole and Howard’s blinds were open, and sun poured through their office window.

“For Joe, it was very personal,” Carole told me. “Whereas for us, it was just another one of these bad guys that we are trying to make people aware of.”

Carole Baskin at Big Cat Rescue in Tampa, Florida.

Carole said one of them is Lowe. When I visited the G.W. Park in May, its squalid conditions were under his and Lauren’s stewardship. Lowe told me he’s had “five consecutive perfect unannounced USDA inspections”, spends $4,000 weekly on food, and that the big cats are “happy.”

One employee, Taryn Walker, said the new owners are incompetent, and feed the cats chicken rather than more expensive and nutritious red meat. When Taryn reported the park for mistreating its horses, Lowe called her a “c-nt” on his Facebook page, and reiterated it to me, claiming she tasered tigers: “Show your face here again you bitch, I have a rake and shotgun with your name on them.”

Lowe told Mark Lewis he was installing a drive-in theater at the park. He’d convinced Joe Barth, his Beaufort neighbor, to move his theater. Then he reneged on the deal and, Barth claims, stole the movie equipment. He still fears for his safety.

In November 2017, cops raided the Lowes’ Las Vegas property and impounded a tiger, a liliger, and a lemur, which vets announced were sick. They cited Lowe for doing business and handling animals without a license. “Who cares?” Jeff told me. “I got caught with exotic animals in a city that bans exotics. It’s a municipal court ticket just like jaywalking.”

Lowe planned to close Wynnewood and reopen a far bigger park, called Red River Safari, in Thackerville, near the giant WinStar World Casino on the Oklahoma-Texas border. He advertised labor to build the site on Craigslist, but as yet the scheme hasn’t progressed.

Joe hasn’t expressed any remorse for his actions. The first time we spoke via phone, Joe asked if I could pass a message to Donald Trump Jr. He believes he’s been set up like Terry Thompson from Zanesville—a “political prisoner,” he told me. After the conviction, Joe wrote to President Trump, begging for a pardon. He complained to me about conditions in jail, saying humans are treated worse in American jails than animals under USDA regulations.

Joe and Dillon Passage are still married. Dillon wouldn’t speak to me and Joe wouldn’t reveal his location. Danny Maldonado questions whether Travis’ death was accidental. He wants the ashes Joe gave him tested.

John Finlay lives in Davis and holds a steady welding job. Having a daughter helped him focus after his years at the park, he told me, when we met at a cafe in Norman, near Oklahoma City. He’s happy, and has a girlfriend. “Whether he knows it or not, he did mentally abuse me and controlled me,” he told me. “But I’ve actually got it figured out now.”

John will never step foot on the park again: Lowe threatened to shoot him if he does. “Trespassing animal abusers will be shot and killed,” Lowe told me.

“He’s as bad as Joe, if not worse,” John spat.

Jeff Lowe and big cats.

Francis and Shirley are frail and may never see their youngest son free again. Yarri, Pamela, and Tamara aren’t close. They all squabble over the land in Kansas, whose rights they now share with the Baskins.

Despite his lies and manipulation, I enjoyed speaking to Joe. He’s charming and an engaging speaker. He made me feel I was his best friend, telling me that, as a British writer, I could stick it to the American press who “make everything look horrible.” If he thinks you’re a potential enemy, everything changes. When he discovered I was reporting his true story, Joe called me a “bully” via his jail’s commissary (called Tiger). He told others I couldn’t be trusted.

Joe never confessed a picayune of regret to me. “Am I going to take the fall (for stuff) that everyone did wrong?” He asked. As our conversations continued, he grew more skittish and hostile.

Then, just before this story went to press, Joe burst into a tirade against everybody, including me.

“You bet I was cruel,” he wrote me. “I am an asshole to work for. Peoples’ lives depend on me making them follow rules. They let out the chimps, tigers, leopards, wolves—you name it—and guess who’s ass was always in trouble when they did… Who the hell do you think is paid to do a job? The staff. Why was I written up: because the staff won’t do their job. But I am supposed to be nice?

“Go fuck yourself.”

“Kiss my ass right here from jail,” he posted to Facebook. “None of you will ever come close to knowing the stress it took daily to deal with keeping hundreds of people alive, just so a bunch of people, that their own families threw out, could not appreciate a job and a home.”

“I am proud of what I did in my life and any loser that says otherwise had the same chance—they just fucked it up. That zoo is closing and the new one will never open. I promise you that, ‘cause a bunch of people are going to jail. I am making sure of that.”

The Tiger King was trying to claw back power, but he has nothing left but his roar. He carved a kingdom from dust, cleaved from the world by a river and a freeway. Wild people tame wild animals and he ruled them all. Then he watched it crumble, and another man took his throne. Joe lived by the laws of the jungle. The laws of man weren’t nearly as easy to master. Now he’s the one behind bars.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.