Joe Manchin suddenly seems to influence everything Washington does. The West Virginia senator says he wants to make Congress ‘work again’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

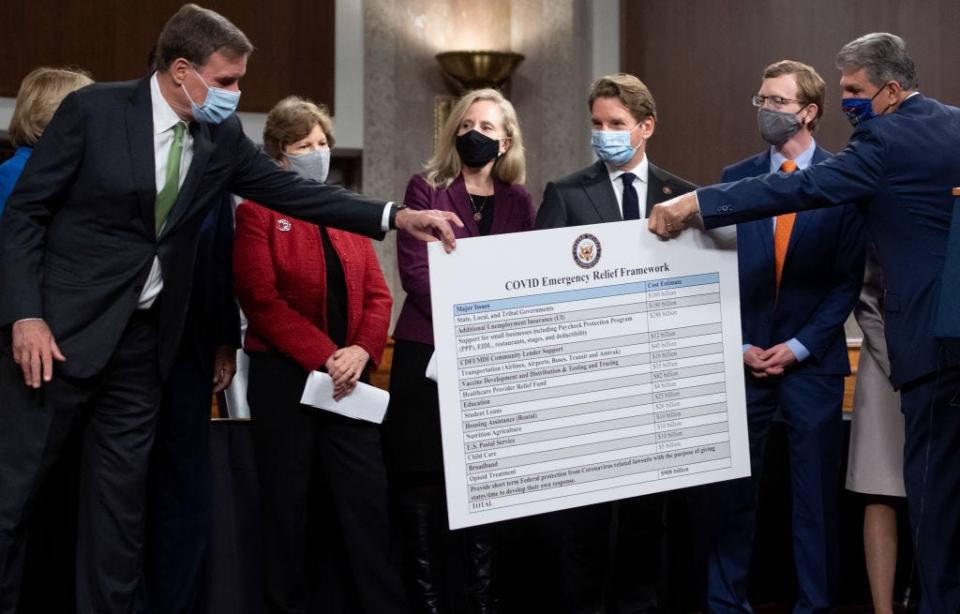

FARMINGTON, W.Va. – For more than nine hours, Joe Manchin wouldn't budge, and the fate of President Joe Biden's $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief bill hung in the balance.

The Democratic senator from West Virginia opposed the bill's inclusion of a $400-per-week federal unemployment bonus, concerned raising it from $300 might entice some to live off government payments rather than seek work. As the hours ticked by on Friday March 5, his Democratic and Republican colleagues took turns huddling with him. By nightfall, Manchin signed off on a deal extending the $300 benefit five more months that included tax relief. The bill passed the next day.

It was one of many moments in the first 100 days of Biden's presidency when Manchin, 73, commanded the attention of Washington.

Q&A with Joe Manchin: Sen. Joe Manchin says Trump ‘called me all the time.’ Senator says he was ready ‘to stay and fight’ during Capitol riot

As the most conservative Democrat in a polarized and evenly divided Senate, Manchin influences almost everything Congress touches these days: efforts to raise the minimum wage to $15, increasing taxes on corporations, the size of an infrastructure bill, even whom Biden is able to install in his Cabinet.

Friday, Manchin told a West Virginia radio station he opposes a just-passed House bill to grant the District of Columbia statehood – another liberal plank – because such a move should be done by constitutional amendment.

Manchin, who credits his outlook to his upbringing in tiny Farmington, insists he's the same guy he's always been: a moderate interested in finding unity in a city defined by division. In a 50-50 Senate, a single Democratic senator can wield outsize clout simply by threatening to withhold a vote on key legislation.

Manchin opposes DC statehood bill: Joe Manchin deals blow to efforts to make nation's capital the 51st state

It's given Manchin a chance to shape not only what's gotten approved in the important first months of the Biden presidency but also how. To Manchin, legislation before the Senate should be negotiated with both parties even if only one side supports the final product.

He opposes doing away with the filibuster, a legislative hurdle many Democrats want to eliminate because it can prevent congressional adoption of large-scale priorities such as climate change legislation, large tax hikes on big business and a broad expansion of safety net programs.

In a wide-ranging interview with USA TODAY, Manchin said he never sought such influence. Asked about all the labels he's been tagged with lately – president of the Senate, an obstacle to progress, a defender of the status quo – Manchin demurred. So who is he?

"Not those people," he said flatly, sitting in his Capitol Hill office bedecked with West Virginia mementos and family photos, including from his Farmington youth. "They talk about all this power stuff and everything. I didn't elect to be the 50th vote. I didn’t elect for this position."

The senator known for his folksy approach said he won’t stand by watching Congress being pulled apart by forces on the far right and the far left whom he contends are more interested in one-sided victories than lasting solutions.

“I've watched people who had power. It destroyed them. They let power go to their head. I've watched people that sought power thinking it would really make them something, and they destroyed themselves. And I watched people that basically took advantage of a moment of time and made a difference,” he said. "I'd like to be that person.

“If I can make a difference, make this place work again,” he continued. “Save the Senate. Save Congress as we know it."

The left's frustration with Manchin

Though Republicans applaud him for tapping the brakes on massive legislation such as the COVID-19 relief bill that passed in March and the $2.25 trillion infrastructure bill Biden proposed, some Democrats see Manchin as an impediment to the nation's necessary development.

Manchin's opposition to doing away with the filibuster has left him battling important voices in his party, including Hillary Clinton. She said GOP rigidness on issues such as ballot access means Democrats are unable to achieve their agenda despite controlling the White House and both chambers of Congress.

More: Group of Senate Democrats and Republicans vote to keep $15 minimum wage out of Biden's COVID-19 bill

"We can preserve the filibuster, or we can preserve the voting rights of people of color," Clinton tweeted. "But we can't do both."

Vermont independent Sen. Bernie Sanders said he'd have "no problem" going to West Virginia to make his pitch for a $15 minimum wage, free national health care and significantly higher taxes on corporations, all things Manchin resists to varying degrees.

"I think we need a grass-roots movement that makes it clear to Joe Manchin and everybody else in the United States Senate – including Republicans – that the progressive agenda is what the American people want," Sanders told the Mehdi Hasan Show this month.

For Manchin, a former governor who counts the late Sen. Robert Byrd, D-W.Va., as a mentor, and who represents one of the country’s most conservative states, forcing people to negotiate with each other is the only way he's ever known.

“I haven't changed,” he told USA TODAY. “I'm fiscally responsible and socially compassionate. It’s the way I was raised. If you went to Farmington, you can tell exactly where I came from.”

'Home of Joe Manchin III'

Farmington, West Virginia, is a tiny town nestled in Appalachia’s rugged coal country near the Pennsylvania border.

It’s where Manchin, the high school quarterback, absorbed lessons of humility, compassion and diligence, working in a grocery store run by his grandparents, Papa Joe and Mama Kay. He helped dispense food to miners and their families – especially when tragedy struck Nov. 20, 1968, when an explosion in the Consolidated Coal No. 9 mine killed 78 miners.

The disaster, one of the deadliest in U.S. history, led to passage of the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act the next year.

Manchin has held just about every elective office in West Virginia: state delegate, state senator, secretary of state, governor and now U.S. senator. He lost the 1996 gubernatorial primary but revived his political career four years later after patching frayed relations with the state's unions.

West Virginia’s senior senator lives in Charleston with his wife of more than 40 years, Gayle. The avid pilot, hunter and motorcyclist said he's never forgotten what he learned decades ago growing up in Farmington.

“Accountability and responsibility," he said during the interview. "You're responsible for your actions.”

Farmington, which has a population of less than 300, has not changed much since Manchin left as a young man decades ago. Main Street, which runs through the Marion County hamlet about 5 miles northwest of Fairmont, is dotted with a few businesses and a post office. A sign on Route 250 leading into town offers a nod to its most famous son: "Home of Joe Manchin III, U.S. Senator, 34th Governor."

The brick house where Manchin grew up remains (albeit bigger and occupied by sister Paula). It sits next to Buffalo Creek and the abandoned railroad tracks that carried trains Joe occasionally jumped on for a short joy ride.

Manchin's brother John, a doctor, opened up the Manchin Clinic in town. The grocery store he worked at is gone, though one of its original signs heralding "Papa Joe's famous meats," adorns the side of another building. After years of not having a general store, Manchin helped the town attract a Family Dollar store a few years ago that became a de facto successor to his grandfather's business.

More recently, he helped broker a congressional deal in 2019 to keep health care and pensions for tens of thousands of retired miners and their families.

"Saved our pension. Saved our insurance," said Donna Costello, a former Farmington mayor whose husband was a coal miner for 47 years and who worked with Manchin to open the Family Dollar store. "Joe does not forget where he came from."

Manchin doesn't get back to his home town much these days. And he's lost the flat top he got at the local barber store every Saturday. But the senator said he still carries "the lessons of life" he learned from the tightknit family he grew up in.

Manchin would never have entered politics had he listened to his father.

He'd seen his family take care of down-and-out neighbors for years and greatly admired his uncle A. James Manchin, West Virginia's onetime secretary of state. But when Joe, a businessman at 35, broached the idea of running for the state Legislature, his father, John, who ran a furniture store in Farmington, tried to talk him out of it.

"It's a horrible sport. It's awful. Don't get in it," the senator recalled the paternal admonition. But his father ended up cheering him on when Manchin ignored the advice and won a seat in the West Virginia House of Delegates in 1982, then the state Senate in 1986. John Manchin died before he got to see his son rise to be governor in 2004.

“I think that Joe, as he was going along, he knew where he was going, what he was working for,” said Meredith Banick, a family friend and the wife of a retired coal miner who still lives in Farmington. “And you could see that he had the possibility of going into politics. Shake the hand. Look you in the face. Give you some time. Make you feel like the person you are. Listen to you. Hear you out. Not walk away.”

Manchin holds huge sway on climate and infrastructure

Since January, Manchin has been instrumental in killing a plan to raise the federal hourly minimum wage to $15 (he wanted $11) and limiting wealthier households from receiving payments in the COVID-19 relief bill. His thumbs up (Interior Secretary Deb Haaland) or thumbs down (budget director nominee Neera Tanden) has been a deciding factor on Biden Cabinet appointees.

His biggest impact could come as Biden tries to persuade Congress to pass his ambitious climate and infrastructure plan dubbed the American Jobs Act.

Manchin reiterated to CNN what he told USA TODAY in April, that he supports an infrastructure bill more focused on bridges, roads and broadband without the social safety and climate change programs Biden proposed. The senator opposes Biden's plan to hike the corporate tax rate from 21% to 28% to pay for it. After Manchin said he could go no higher than 25%, Biden said he was open to negotiation on the package.

As chairman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, Manchin stands in the way of Biden's ambitious climate change proposals to cut fossil fuel emissions and end subsidies for coal and oil.

For most of the interview with USA TODAY, Manchin spoke in measured tones – about the mob attack Jan. 6 on the Capitol, Biden's liberal agenda and his own push for bipartisanship. But asking him about how coal miners and their families felt about Washington trying to end their livelihoods touched a nerve.

"You want to know how West Virginia feels? It feels like returning Vietnam veterans," he said, his voice rising and quickening. "We're not good enough, we're not clean enough, we're not green enough and we're sure as hell not smart enough for you, so you just cast us aside and go on. If it wasn't for West Virginia and people like West Virginians who mined the coal, made the steel, built the factories – we've done all the heavy, dirty lifting, and now cast us aside. … Sometimes they forget how we got to where we are."

Manchin: a Democrat in a red state

Those who know him say Manchin's politics have evolved with the times.

His loss in the 1996 gubernatorial primary to a liberal candidate forced the businessman to forge a relationship with unions who helped revive his political career.

“That’s where he learned the big lesson, and that’s where you see he’s able to talk to all sides today," said Huntington, West Virginia, Mayor Steve Williams, who has known Manchin since they began serving together in the Legislature about 30 years ago. "Joe was very conservative, strictly business: 'This is the direction that we have to go in. To create jobs, we have to have a business-oriented governor.' (His opponent) ate his lunch with labor.”

After his defeat, he worked to appeal to labor unions, and in 2000, he won the job his uncle once held: secretary of state. Four years after that, he won the Governor's Mansion.

As governor, he pleased the right by privatizing an insolvent workers-compensation insurance system and cutting business taxes and pleased the left by abolishing the sales tax on food and enacting a law to limit emissions from coal-fired power plants, according to Chris Regan, a Wheeling, West Virginia, lawyer who served as vice chair of the state's Democratic Party.

"The senator doesn’t have an overarching ideology like Bernie Sanders or (Kentucky GOP Sen.) Ron Paul does," Regan wrote in The Atlantic magazine. "He is not determined to bring home pork in the way that his predecessor, Robert Byrd, did. Manchin has skillfully managed his image, to stay viable in a state that went from a Democratic to a Republican majority. He has done that by having a keen sense of what issues and bills are popular at any given moment and of how he can be seen as being on the right side of those issues for the electorate – no matter which party is in favor of them."

Williams said it's not just that Manchin can sense what most voters want, it's also that he outworks the competition.

"He can’t be defined by others," the mayor said. "You go around the state, everybody knows Joe Manchin. Everybody has their own Joe Manchin story.”

For Manchin, being bipartisan isn't just a matter of principle. As a blue dot in a red state, it's a matter of survival.

When he was first sworn in to the state Legislature in 1983, Democrats outnumbered Republicans by more than 2 to 1, according to voter registration numbers. Back then, the governor was a Democrat. Both U.S. senators were Democrats. As were all four members of the U.S House.

Now, the governor and every federal officeholder except Manchin is a Republican. Not surprising in a state Donald Trump dominated in the presidential races in 2016 (by 42 percentage points) and in 2020 (by 39 points).

John Kilwein, an associate professor of political science at the University of West Virginia in Morgantown, said Manchin works hard to get around the state, no matter how red the community is, and he understands how popular issues such as coal, gun rights and affordable health care are among Mountain State voters.

“He’s still successful because people remember he’s one of their own. But if you look at his margin of victory, it’s getting tougher," Kilwein said, referring to his narrow reelection victory in 2018 over GOP state Attorney General Patrick Morrisey. "He doesn’t want to upset an electorate that has become increasingly more conservative, an electorate that distrusts the Democratic Party. ... I can’t imagine a Democrat winning statewide in West Virginia other than Joe Manchin."

Democrats know he's important to their power

Manchin has been a double-edge sword to his Democratic colleagues since he won a special election in 2010 to replace Byrd. They understand how important his seat is to them even as they fret about how he'll vote on issues.

It didn't make environmental or gun control activists too happy when his most prominent campaign ad in the 2010 campaign featured him firing a shotgun at a copy of the Senate bill to limit greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels such as coal.

His votes bucking his party to confirm former Alabama GOP Sen. Jeff Sessions as President Trump's attorney general in 2017 and Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh a year later roiled liberals who slapped the social media moniker "#TraitorJoe" on him.

Their anxiety no doubt rose amid rumors Trump was considering him for energy secretary or when he flirted last year with the idea of running for governor again. They staged an "intervention" in 2018 when he was mulling an exit from the Senate.

Democratic senators told USA TODAY they don't publicly begrudge Manchin; they wouldn't be in the majority (Vice President Kamala Harris as president of the Senate casts tiebreaking votes) if Manchin's seat was held by a Republican.

“Joe has been in public service in West Virginia for a long, long time, and I have no doubt that he does his best to try to help the people of West Virginia," said Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a leading liberal voice in the party who has worked with Manchin on expanding certain Social Security benefits.

"We’re a big tent. Takes a lot of different opinions. Joe’s out there fighting for what he believes in. Bernie (Sanders) is, too," said Montana Sen. Jon Tester, a moderate Democrat who joined Manchin in opposing the $15 minimum wage. "I don’t have a problem with either one of them."

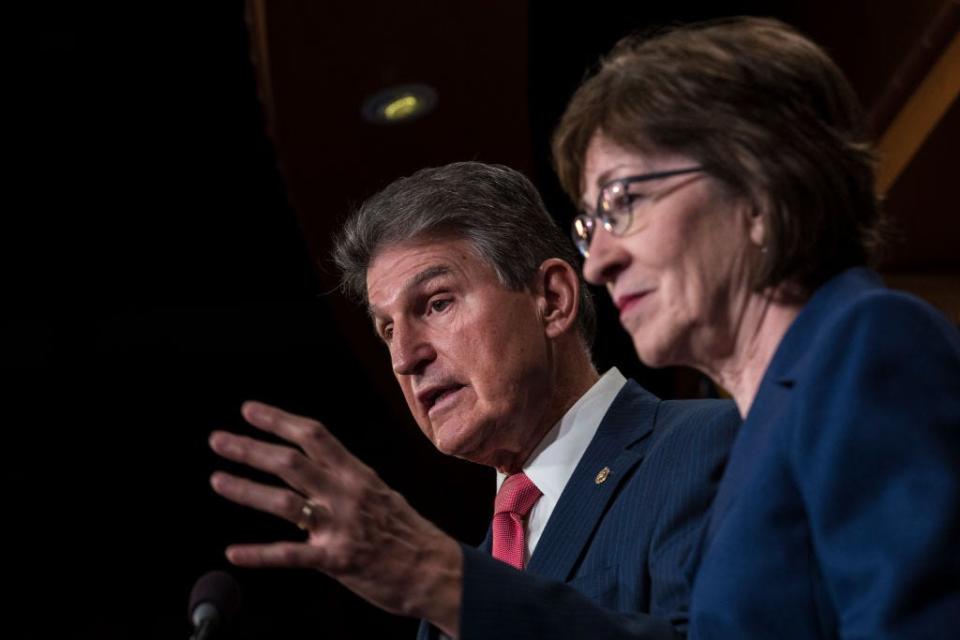

Manchin counts Republicans among his Senate friends.

He frequently dines with Maine Sen. Susan Collins and other GOP moderates to talk policy. He's invited some of them to "Almost Heaven," his Washington houseboat that borrows its name from "Take Me Home, Country Roads," John Denver's homage to the Mountain State.

He refuses to campaign against Senate GOP incumbents, "so they don’t look at me as an enemy.”

Costello said Manchin's small-town upbringing is why he reaches out to Republicans. And it helps explain his mission to keep the filibuster.

“He’s about bringing everybody to the table," she said. "And at the end of the day, you may not win it all. Somebody leaves with a little bit of something. Somebody else leaves with a little bit of something. And they both come out winners. It’s better than having a whole lot of nothing, isn’t it?”

And he's been consistent. Manchin was one of only three Democrats to oppose his party's successful effort in 2013 to eliminate the filibuster for most presidential nominees. He opposed the GOP move in 2017 to eliminate the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees.

The attack Jan. 6 on the Capitol by a pro-Trump mob reinforced his view that the filibuster must remain, he said. And it's why he opposes efforts by Democrats to push through controversial portions of Biden's infrastructure bill through a special procedure called reconciliation that requires only a simple 51-vote majority rather than the 60 votes needed to overcome a filibuster.

"It was never what reconciliation was designed for," Manchin told USA TODAY. "And if they want to get exemptions so they can use it as much as they want to run this Congress, can you imagine when our Republican friends get in control? And it'll happen. It’ll go full circle again."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Joe Manchin: His huge sway in Congress and his West Virginia roots