Joel Coen wouldn't have made 'Macbeth' with his brother Ethan. Here's why

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Despite all his experience, Joel Coen knew that his adaptation of “The Tragedy of Macbeth” was not a sure thing. “I was very nervous doing this movie, but at the end of the day, really why? There’s no bad thing that can happen,” he says. “I could fall flat on my face, but who cares?” On the other hand, “if you don’t take a risk and do something,” that is where danger lies.

Don’t be fooled. Don’t misunderstand. Just because it’s only Joel Coen’s name on the writing and directing credits for the exceptional “The Tragedy of Macbeth,” just because he sits by himself on the terrace of a Santa Monica restaurant, with no sign of his brother and longtime collaborator Ethan, don’t think he’s suddenly soured on directing in tandem. Quite the contrary.

“It’s fantastic, there’s nothing like it, when people ask if I have directing advice I tell them, ‘find a partner,’” Coen says, lighting up. “It’s an enormous advantage in every way. You have someone you can turn to when things go pear-shaped and, in crass terms, you can gang up on people. I missed him a lot.”

But collaborating with someone (in Joel and Ethan’s case on 18 features, including the Oscar best picture winner “No Country For Old Men”) by definition means “you’re pursuing things that are mutually interesting, which is what we’ve been doing for 35 to 40 years.”

So when Ethan told his brother at the close of their last film, 2018’s “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs,” that “‘I think I’m going to change it out and do some other things for awhile,’" Joel reevaluated. "I knew I’d be directing the next one by myself," he says. "If I was working with Ethan I wouldn’t have done ‘Macbeth,’ it would not be interesting to him.”

Again, don’t misunderstand. Though Coen’s “Macbeth” starring Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand is the product of a beyond-thorough examination of Shakespeare’s play, don’t assume the film is the end product of a lifelong obsession. On the contrary, it just kind of happened.

Coen’s first exposure to Shakespeare came as an 11-year-old seeing an American company doing “Twelfth Night” in a park in suburban Minneapolis. “I knew nothing about Shakespeare, 90% of it I didn’t understand, but I remember being absolutely enthralled by the experience of watching it. The story was accessible to everybody.”

In the years since, though he’d seen a smattering of takes on “Macbeth,” including Akira Kurosawa’s brilliant “Throne of Blood” and “strange, obscure movie versions that had only a tangential relationship to the play,” Coen says flatly he was “not a student of Shakespeare in any way, shape or form.”

But then his wife, actress McDormand, was “planning to do a production of ‘Macbeth’ on stage and asked if I would direct. I said I wouldn’t do it on stage but if you want to think about it as a movie we can do something interesting.”

McDormand ended up on stage as Lady Macbeth at the Berkeley Repertory Theater in 2016 and Coen continued considering a film version. “It’s a function of the way my brain works,” he explains. “If I can think about it in cinematic terms, then I can get my head around it.”

More than that, when he focused on the fact that the play “was really a murder story, about a couple plotting a murder, I felt like I was on comfortable ground.”

Because four-time Oscar winning McDormand is in her 60s (as is Coen), this Macbeth marriage would not be the union of two young, upwardly mobile spouses but rather a strong bond of age and experience.

“She’s a post-menopausal Lady Macbeth, she hasn’t delivered an heir, she’s not going to deliver an heir, and that plays a central part,” Coen says. “In the context of Shakespeare it’s a good marriage, they love each other. They happen to be plotting a murder, but hey, it’s OK.”

As to who would play the other half of the couple, that almost seemed a foregone conclusion to Coen. “As soon as we decided it would be an older version, who is a contemporary of Fran’s? What actor is going to be a worthy adversary, is going to be a balanced player in terms of power? The list isn’t long.”

It turns out Washington had been on Coen’s radar for some 40 years, starting when he saw the then-unheralded actor on Broadway in the Negro Ensemble Company’s “A Soldier’s Play.” “I thought, ‘Who is this guy,’ he had such power on stage.

“We’d had a lunch a number of years ago, we talked in a general way about working together if the right thing came along, that kind of conversation. When this came up he seemed like an obvious choice. We met once and it was ‘let’s do it.’”

“Macbeth” also provided Coen the chance to work with an actress he’d admired for years, the English stage legend Kathryn Hunter, who gives an unsettling, uncannily disturbing performance as all three of the witches who pronounce Macbeth’s fate.

“It would have been very difficult to make the movie without Kathryn," the director explains. “Nobody can compete with her physical transformance, the level of magic and strange theatricality she brings. I knew she would be extraordinary.”

In fact, Coen reports, when Hunter shot the disconcerting scene where we initially see her, “first the crew put down their stuff and got close to the monitors. Then they moved to the edge of the set. When she finished, they burst into applause. There is no CGI, no tricks. Just Kathryn in costume on a stretch of sand.”

Coen took a similarly old-school approach to turning the play into a script. He spent time with friend and neighbor Hanford Woods, an academic who taught Shakespeare at Dawson College in Montreal.

“I wanted him to explain to me the things I didn’t understand,” the director remembers. “We went through the play line by line. When I asked him what certain words meant he would sometimes say ‘You’re kidding.’

“The rewards of entering that world are so huge. There’s not many plays that can take that kind of deep dive, as much as you go into it, you’re never going to hit bottom.”

Part of Coen’s goal for this process was a screenplay that was “as clear as possible,” that was “accessible even for people who are like this” — he dramatically crosses his arms across his chest — “when it comes to Shakespeare’s language.”

To get everyone on the same page, especially because the film was shot in a brisk 35 days, Coen called for rehearsals, lots of them. Washington, McDormand and the director worked together for months, reading and talking about the play. Then, three or four weeks before shooting began, Coen asked as many of the cast as could make it to come together “and work on it like a play.”

“The actors had different accents, different backgrounds, we were pulling people from everywhere,” the director says. “We had to make a company, so everyone would understand which version we were doing.”

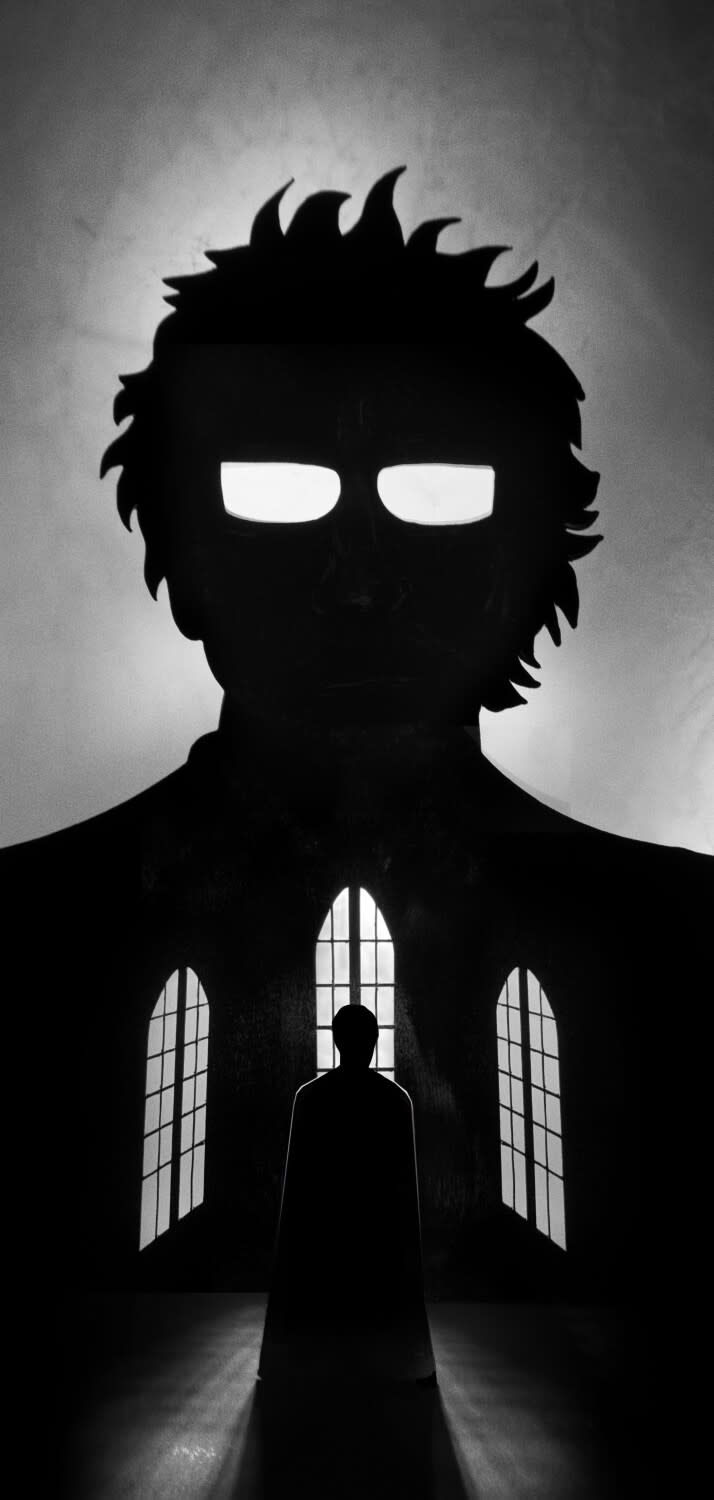

Coen had similarly clear ideas about the highly stylized, distinctive look of the production. Influenced by renowned British stage designer Edward Gordon Craig, it was shot in stunning black and white by Coen veteran Bruno Delbonnel and production designed by Stefan Dechant.

“The intention was never to go the realism way, to do the rented castle version, I was not in the least bit interested in that,” Coen says. “It was going to be something closer to a dream.

“I wanted it to be very much a piece of cinema while preserving the play-ness of it, to never lose sight of the fact that you’re watching a theatrical thing. That drove the whole thing, including shooting in black and white, toward abstraction.”

This philosophy extended to the use of props, where, Coen says, “making things simple and graphic was the way to go. [Cinematographer] Bruno said it was like a haiku. There’s element one, element two, element three. Together you can say whatever you want to say. Everything else is clutter.”

“The Tragedy of Macbeth” was shot on Warner Bros. sound stages in Burbank, the first time a Coen film had been shot entirely indoors, something the director says “seemed like an attractive prospect to me.

“My last movie was shot almost entirely outdoors and it was like four months of 12- to 14-hour days of either freezing or scorching weather. I thought ‘Wouldn’t it be be nice to be on a stage and never have to worry if it’s raining outside.’”

Currently distributed in theaters by A24, “The Tragedy of Macbeth” will begin streaming via Apple+ on Jan. 14. “I’m like a lot of people," the director says, "I’m of two minds” about streamers becoming so prominent. With one caveat.

“When Ethan and I started, studios were able to take advantage of revenue from ancillary markets like VHS as a financial balance to risk-taking,” Coen says. “It made studios more willing to do movies out of the mainstream.

“It’s important that everyone who wants to see one of my films in a theater should be able to. But I’ve never been one of the purists because one of the reasons I’ve had a career is home markets, people watching on TV. It’s responsible for me being able to make movies for 40 years.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.