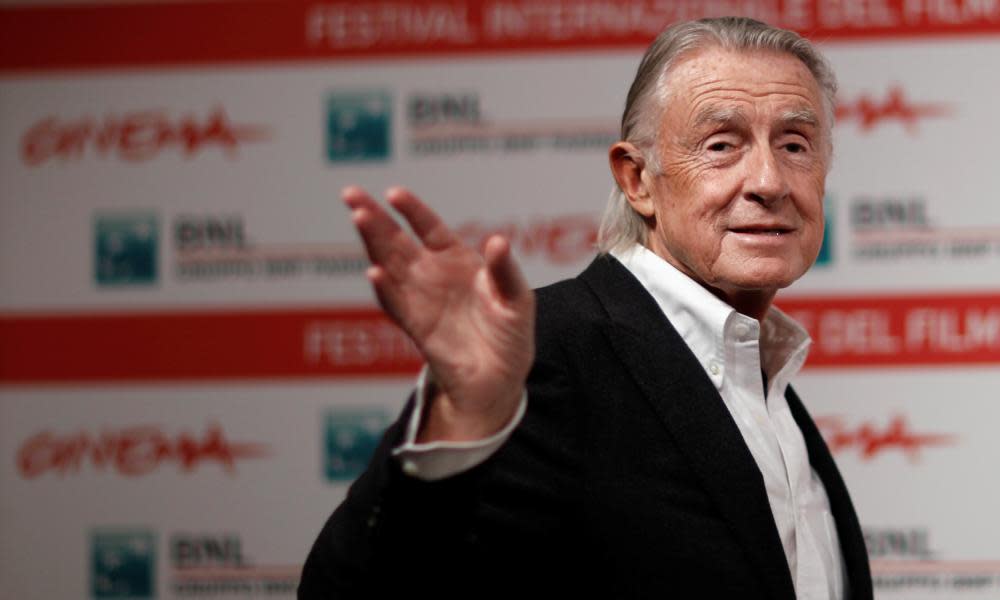

Joel Schumacher: a high gloss, star-making Hollywood showman

The career of Joel Schumacher was that of a classic Hollywood alpha-player in the big-money 80s and 90s: a really smart operator who made a string of good, underrated movies – and whose industry clout was based on delivering effective studio films of so many varying sorts, with high gloss and high profits. He brought out Hollywood Brat Pack movies in the 80s when these were at the very height of fashion, and then showed he could do very well-crafted John Grisham legal thrillers. And much later, he returned to smaller-scale pictures with up-and-coming young actors like Colin Farrell, whose career he nurtured in the early days.

Related: Joel Schumacher, Batman Forever and The Lost Boys director, dies aged 80

He had a sharp, shrewd sense of genre and casting, knew how to make different types of picture work, and his watchable movies nearly always made big money; they were enjoyed by the public and perhaps also – secretly, grudgingly – by the press. He was never a director who bathed in critical esteem. Schumacher never got a big glittering prize, although his great big high-concept talking point Falling Down, with Michael Douglas suffering an uncool meltdown of daringly anti-PC rage in the burning LA sun, was entered into competition at Cannes. Actually, Schumacher was more likely to get Razzies and chortling takedowns from the snarky pundits, and in 1999, he got a volley of derision for 8mm, his (admittedly awful) noir drama set in the snuff business starring – gulp! – Nicolas Cage. Also scorned were his two Batman movies Batman Forever with Val Kilmer – which was actually rather good – and Batman & Robin, starring a distinctly sheepish-looking George Clooney. In fact, by the end of the 90s, Schumacher himself was a film-maker who resembled a kind of Batmobile, becalmed in the Batcave: huge, sleek, impressive, technocratic, immobile, but capable of a colossal burst of speed when treated correctly.

Schumacher made his name with St Elmo’s Fire in 1985, the coming-of-age film which introduced the world to a raft of pretty boys and girls: among them Emilio Estevez, Rob Lowe, Ally Sheedy and Demi Moore. The Lost Boys in 1987 was a rather brilliant black-comic satirical picture about the nightmare of being young, a vampirish spin on Peter Pan – it’s one of the great kids’ heroism movies of the 1980s, something to put alongside Spielberg’s ET or Richard Donner’s The Goonies. His Flatliners of 1990, with Kiefer Sutherland and Julia Roberts, was another very potent example of Hollywood jeunesse dorée given a dark spin. Five unfeasibly good-looking medical students investigate what lies beyond death by giving themselves near-death experiences. Perhaps without meaning to, Schumacher had intuited the “emo” trend, albeit with a very groomed image.

Schumacher’s Grisham moves – The Client (1994) and A Time To Kill (1996) – were quite different to this, and indeed different from each other, with The Client more purely procedural and A Time to Kill more concerned with racism and misogyny, showing the cynicism and power-plays involved in lawyers trying to get juries whose ethnic mix is to their liking.

And yet for all Schumacher’s golden touch with smart movies which pleased the public, he seemed to falter with the genre which was in the next 10 years going to evolve into one of the most lucrative of all: the superhero movie. And perhaps it was simply because he was out of joint with the times. His instinct was to tilt Batman towards comedy and wackiness and fun, in the same way that the Christopher Reeve Superman pictures had developed, or, you might say, unravelled. But the increasingly important fanbase wanted something much more deadly serious, which they were to get in the next decade with the mighty vision of Christopher Nolan. Perhaps Joel Schumacher thought that these were not grownup pictures, and couldn’t fake it.

He dialled it down for small-scale pictures after that and gave us the outrageous, uproarious Hitchcockian micro-thriller Phone Booth in 2002, in which Colin Farrell plays Stu, a married media publicist in New York who’s in the habit of calling the young women he wants to seduce from an old-fashioned phone booth so his wife won’t see the strange number on his mobile bills. But then the phone in the booth rings; he picks it up and the voice on the other end claims to be a lone gunman with Stu in his crosshairs and if he replaces the receiver, he’s a dead man. The whole film is just about Stu, imprisoned in the phone booth, squinting up at the surrounding buildings, babbling, pleading, blustering, not willing to gamble that the man is bluffing or lying and just hang up. Or is this the supernatural voice of his own conscience? The film has the brash spirit of Joel Schumacher – in a space the size of an upended coffin.

It’s a good time to re-watch The Lost Boys or Phone Booth – smart, watchable Schumacher films with a sense of humour.