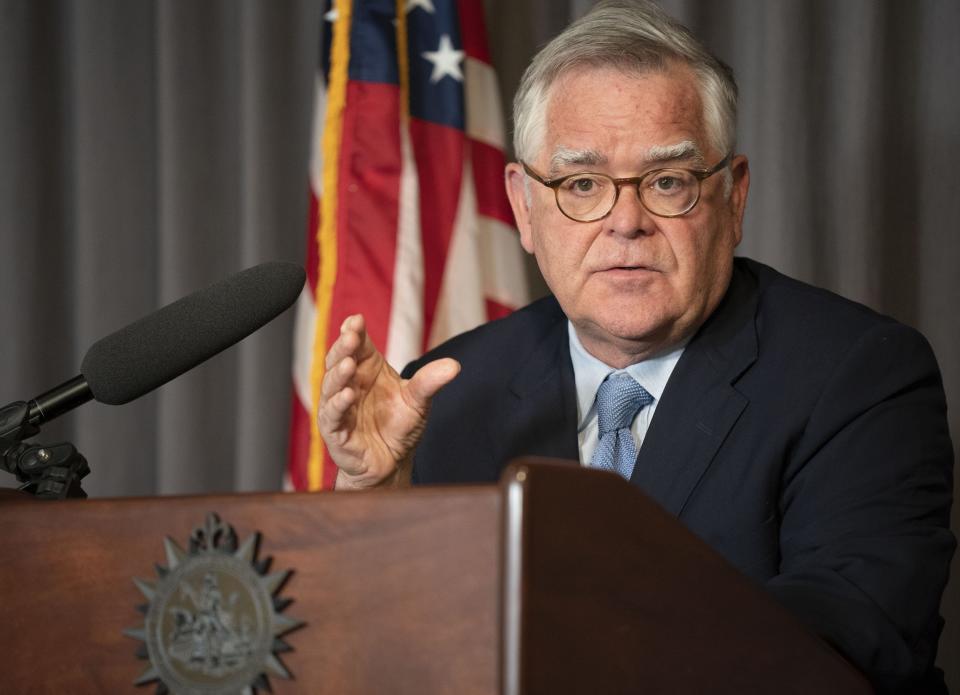

John Cooper, Nashville's 'crisis mayor', reflects on legacy before heading into the woods

Nashville's "crisis mayor" is going off the grid.

Four years of navigating one disaster after another have taken their toll on former Mayor John Cooper. But the 67-year-old developer and community leader is proud of his legacy and hopeful it will endure throughout new Mayor Freddie O'Connell's administration and beyond.

For now, he's turning off his phone and backpacking into nature for a two-week plein air painting course. The adventure is so remote that he had to attest to his physical endurance before booking.

Cooper’s approach as a painter is exactly his approach as a political leader: He focuses on the details. Plein air painting is about capturing the immediacy and the eternal of a constantly moving scene, not unlike the balancing of present and future needs in city government.

“I love painting because it’s something where, if you look more closely at something, it makes it better,” he said. “If you don’t like what you’re painting, then you haven’t looked closely enough at it. It’s sort of like that with everything.”

On election day, Cooper was calm and collected as he savored his last moments in the mayor's office.

"It is the honor of my life to be with the fleet, so to speak, because the response by neighbors to neighbors here is extremely inspiring firsthand," Cooper said. "We saw it over and over again, a genuine emotional outreach to neighbors. You saw that with COVID, the bombing, Covenant, the spontaneous crisis response of good will and concern.”

Movers quietly packed up Cooper’s personal furnishings while he met with his staff, friends and supporters in mid-September.

He decided eight months ago not to seek reelection because his frenetic first term was demanding enough to count for two. He also accomplished most of what he wanted to do in laying the groundwork for an expanded downtown, stronger neighborhood transit hubs and a better staffed, fiscally responsible and organized city.

"Being mayor is the hardest job in America, it’s unbelievably hard," said his brother Jim Cooper, a retired longtime congressman who teaches law at Vanderbilt University. "When he came in, the city was in terrible shape. He righted the ship in short order."

Cooper has enjoyed high approval ratings in office, garnering 57% support in the latest published poll in 2021 by Vanderbilt University.

But the final months of Cooper's term were filled with political turmoil and public scrutiny of his top initiatives — particularly the high-priced development deals. A 2023 Vanderbilt University poll found that 52% of county residents oppose his Titans stadium deal.

Lawsuits brought by his office against the state of Tennessee continue to move through the courts, and questions persist among Metro Council members about land deals he orchestrated.

Before leaving, Cooper made sure to clarify his legacy.

A legacy, by the numbers

One of Cooper's final acts as mayor was to quantify his success in a colorful mailer, paid for with his remaining campaign funds. The eight-page brochure sent to mailboxes, titled "A Report Back to Nashville," outlines his 92% success rate: "Delivered on 47 of 51 campaign commitments made in 2019."

It lists examples of his wins, like "Mayor Cooper secured over $100 million in redirected revenue from tourism via the Convention Center Authority and the tourism promotion fund."

The redirection of tourism revenues began during the 2020 budget crisis and continued until the Convention Center Authority took over the regular costs of downtown public works projects like sidewalk widening, park maintenance and security upgrades like camera equipment.

Cooper has issued similar public report cards before, starting with a 46-page policy guide detailing his campaign promises in 2019.

"He does everything 100% since we were 3 years old," said Robert Davidson, who grew up with Cooper in Shelbyville. "He's always the smartest guy in the class. If I needed to call a friend on 'Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?' I would call John."

Despite his penchant for analysis, it's the unpredicted, unplanned events and responses that may define his legacy.

In 2020, Cooper oversaw a series of natural and unnatural disasters: tornadoes that killed two Nashville residents and destroyed many homes and businesses; the COVID-19 pandemic; prolific Black Lives Matter protests including a riot that set fire to the mayor's office; a budget crisis that included a threatened state takeover; and a Christmas Day bombing that leveled a historic Second Avenue block downtown.

This year, a mass shooting and ensuing raucous political protests in the state Capitol drew national attention.

Six people, including three third graders, were killed when a former student broke into The Covenant School and opened fire before being shot by police. Meanwhile, Tennessee — and especially Nashville — landed at the center of the U.S. "culture war" when state conservatives butted heads with local progressives over abortion, drag queen performances and gun regulation bills.

While political consternation abounded, Cooper kept his focus on the nuts and bolts of local governance.

He created the Nashville Department of Transportation, made large investments in Metro Nashville Public Schools and partnered with the city's historically Black colleges and universities.

“I definitely think we’ve made huge steps in the right direction,” MNPS Director Adrienne Battle said. “MNPS was woefully underfunded for so many years.”

Cooper's administration added nearly $300 million in new annual MNPS funding, much of it going to making salaries the most competitive in the state. Capital spending on four new schools, athletic fields and other facility improvements increased by $500 million.

“His investments have been foundational,” Battle said. “It’s a huge step. One of the strongest points about Mayor Cooper’s leadership is that he does respect and value experts in their field. We had tons of support from him in that regard.”

Metro's budget crisis in 2020 led Cooper to hike property taxes by 34% to prevent drastic cuts in services. The increase was reversed in 2021 because of a state law that resets tax rates when property values rise. Davidson County's rate is now the lowest in the state.

Now the county enjoys an AA+ credit rating and has two months of rainy-day cash in the bank — far from the messy financials of 2020.

"In previous years there had been a lot of chiseling, not replacing fire trucks or lawnmowers for parks. That accumulated. That’s where we were in 2019," he said. "Now we have an integrated process. If you’re doing a dense rezone you have to have a traffic study and the developer has to do mitigations for any loss of service in development."

'From outsider to ultimate insider'

Cooper entered the mayor's office in 2019 as the Council's top critic of development and Metro tax incentives.

But in office, he enthusiastically supported the largest public investment in new development ever. In fact, his focus on a downtown expansion on the East Bank may be his most enduring legacy. The difference in Cooper's deals from prior incentive-driven business is in the fine print.

The $2.1 billion deal for a new NFL stadium with the Tennessee Titans includes a $760 million Metro-issued revenue bond to be repaid with stadium-related revenue.

Crucially, the new stadium lease returns an estimated $1 billion worth of land back to Metro, or 66 acres now mostly used for parking lots. A "stadium village" district will be the first development there, and Cooper's plan rests on private-public partnerships.

A separate deal with Oracle Corp. traded a 50% property tax discount for $175 million in up-front public infrastructure investment at its 65-acre East Bank campus, including a pedestrian bridge connecting both sides of the Cumberland River.

O'Connell's newly appointed Chief Development Officer Bob Mendes was one of the most vocal critics of the stadium deal and others: "It’s too large of a subsidy with not enough benefit for Nashville," he said.

Cooper's term didn't start off this way. Business leaders initially worried he would drive away business. He went so far as to cancel previously approved business incentive arrangements.

He drove hard negotiations for the new Major League Soccer stadium, leading to a monthslong deadlock followed by a compromise for more public benefits.

Some of his time was spent on surprisingly specific details.

He scrutinized design plans for the Nashville Yards development in the Gulch and intervened in the Metro planning process to object to the size of digital signs in the project's entertainment district, though the signs were ultimately approved.

Cooper's approach took a sharp turn in 2021, when negotiations with the Titans got serious and his vision for the East Bank came into focus. Metro was in debt to the team for unpaid maintenance costs, and Nissan Stadium needed an expensive upgrade to remain viable.

So Cooper and the Titans presented the $2.1 billion new stadium proposal. He argued the deal was a vast improvement from the prior lease because it transferred land ownership back to Metro to use for profit-generating development or community projects.

This process led to Cooper's defining project with Planning Director Lucy Kempf: Imagine East Bank.

Last month, a master developer was hired to plan the first new East Bank neighborhood described in “Imagine East Bank,” a Planning Department document that describes a 338-acre redevelopment anchored by a new boulevard better connecting downtown and East Nashville in the inner loop where three interstates converge.

The vision was first presented in August 2022. Cooper painted a portrait of a new East Bank filled with public attractions and modern amenities. He described an activated riverfront connected to downtown and new neighborhoods that would be the envy of cities worldwide. All of this can help fund affordable housing on Metro-owned land.

“We can be the most exciting city in the country,” Cooper told The Tennessean at the time. “This will bring decisive benefits as we move up the ranks of great cities.”

Metro Council members expressed concern with unexpected costs for new infrastructure and public services, but Cooper pointed to the windfall returns promised from new development lease payments and taxes.

Jim Cooper said his brother saw an opportunity and took it.

"People like to blame the Council for everything, but as a business guy he stepped up and did that brilliantly," Jim Cooper said. "He converted from an outsider to the ultimate insider, and that’s incredible flexibility. He was always interested in growth, he just didn’t want insider scamming."

The land deals

Cooper was so impressed with the East Bank development model, which relies on Metro-owned land, that he set his gaze on other parts of town as well. After all, he was elected by voters tired of Metro attention being focused on downtown.

Last year, Metro paid $44 million for the long-dead Global Mall at the Crossings, formerly Hickory Hollow Mall. The Antioch mall is surrounded by thriving businesses including Ford Ice Center, Nashville State Community College and a Nashville Public Library branch. But redevelopment of the mall has proven too difficult for former owners.

Cooper, however, said Metro is uniquely positioned to enliven the property and profit from its ownership. But his initial plan to partner with Vanderbilt University as an anchor tenant fell through during negotiations. Instead, he envisions demolishing the mall and building a mixed-use development with an expanded transit hub.

“Housing, schools, a trail and a park in place of the mall,” he said, describing new plans. “Would it have been easier if Vanderbilt came and created another 100 Oaks? Yes, absolutely, but this is better. I’m super excited because maybe we sell affordable units, not just rent affordable units.”

He also spearheaded the $20 million purchase last year of the historic Tennessee School for the Blind Colored Department at 88 Hermitage Avenue near Wharf Park and Rolling Mill Hill. Restoration is anticipated to cost $8 million, and there is yet to be a clear development plan. But Cooper is sure it’s a sound investment.

“This creates meaningful park connections for the first time throughout Nashville,” Cooper said. “It’s creating an amazing park that connects to the Oracle bridge and the park in front of a domed stadium out to Shelby Park.”

Critics say it’s not a practical use of Metro funds.

“There just isn’t a strategic plan for these,” Councilmember Emily Benedict said. “The negotiations with Vanderbilt weren’t as far along as I expected, and that was extremely disappointing. I think the School for the Blind is a good thing to buy, but I would rather have seen us acquire the Morris Memorial Building.”

But Cooper insists he considered all options and chose what’s best.

The vision will become clearer with time, he said.

“Each of these things that seem bold at a time, in a unit, fit together in a pattern of excellence for a community,” Cooper said. “This is the future of Nashville. Strong neighborhood nodes that are scattered but connected.”

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Nashville Mayor John Cooper reflects on legacy before going off grid