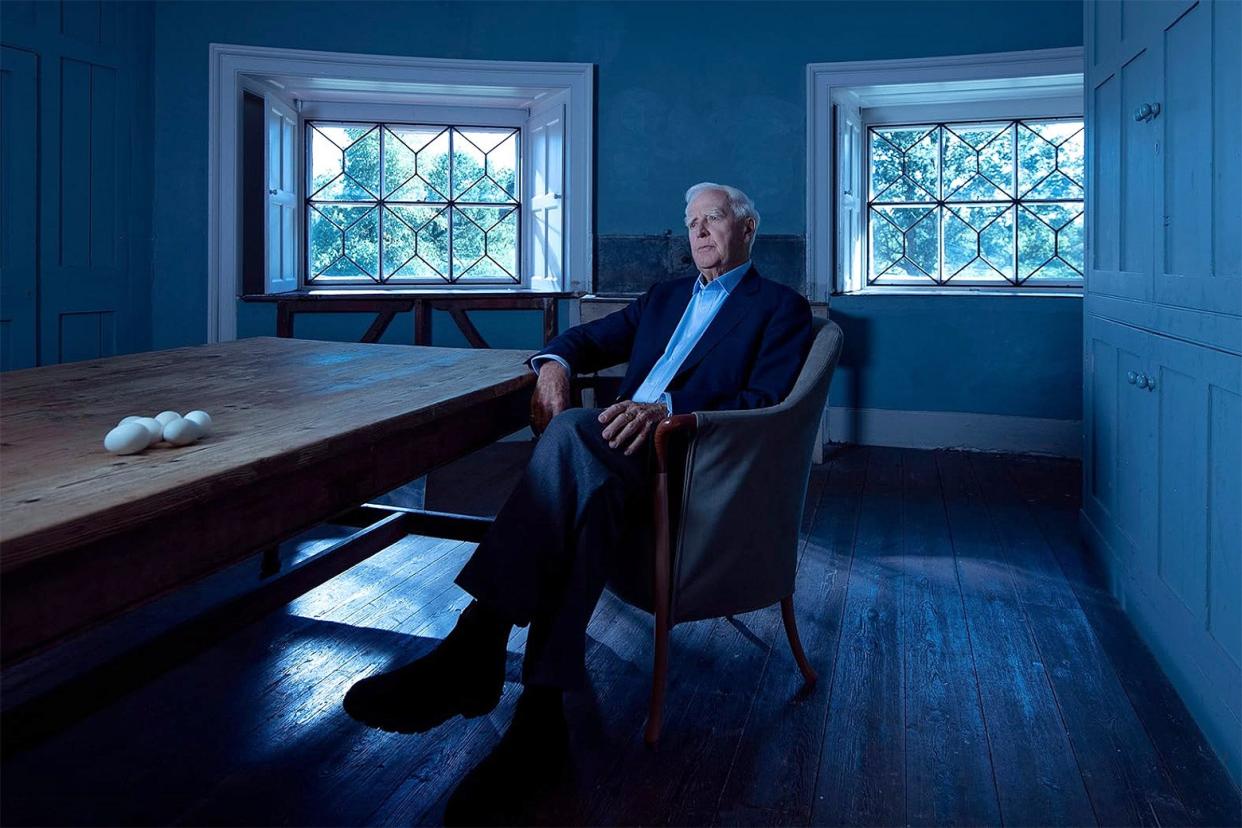

John le Carré Spent His Life Fooling Everyone. Did He Fool Errol Morris?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In The Pigeon Tunnel, Errol Morris’ new documentary about John le Carré, the novelist explains that he never underwent psychoanalysis because he was afraid that too much self-knowledge would crush his creativity. Le Carré—real name David Cornwell—was the most celebrated spy novelist of his time (arguably of all time). He was also a self-confessed chronic fabulist. Lying, he stated more than once, is the essence of both espionage and fiction writing.

That claim about never undergoing analysis? It might be technically true. Cornwell’s biographer, Adam Sisman, however, describes coming across, while working among le Carré’s archives, a “long document that he had written in 1968 for a psychiatrist about his sexual history, which I suspect that David might have forgotten.” Did Cornwell undergo traditional psychoanalysis? Maybe not, but he certainly took at least a stab at therapy of some kind. In 45 years of filmmaking, Morris has interviewed characters ranging from eccentric obsessives (1997’s Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control) to war criminals (the Academy Award–winning The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons From the Life of Robert S. McNamara and 2013’s The Unknown Known, about Donald Rumsfeld). But rarely has he depended more for a film’s effect on the viewer’s knowledge of details not conveyed in the film itself.

Sisman published the original version of his biography in 2015. Cornwell died in 2020. This month, Sisman will publish The Secret Life of John le Carré, a book revealing how much control Cornwell exerted over the 2015 book and all the material Sisman was required to leave out, particularly on the subject of Cornwell’s compulsive philandering. This isn’t exactly a revelation; last year, one of Cornwell’s many lovers, Suleika Dawson, published The Secret Heart, a racy memoir of their affair. But Sisman finds links between each adulterous infatuation and specific le Carré novels, including locations finagled into plotlines to justify “research trips,” whose main objective was hooking up with some woman.

Early in The Pigeon Tunnel, which bears the same title as le Carré’s anecdotal memoir, published in 2016, the unseen Morris observes that in the novelist’s stories “there are dupes and string-pullers, those in control and those controlled by others.” The implied question: Which of these two men will play each role? In a contentious interview with the New York Times’ David Marchese, Morris responded defensively to what he perceived as Marchese’s suggestion that he should have pushed Cornwell to discuss his infidelities. But Morris himself is as wily a character as Cornwell, and if he could not get Cornwell to address his impressive campaign of adultery directly—Cornwell looks straight at the camera and states, “I’m not going to talk about my sex life any more than you would”—in the end, Morris got to control the final edit.

Just how relevant is Cornwell’s sex life to his books? Sisman would argue very much so. Not only, he maintains, was each of le Carré’s best novels inspired by a particularly compelling paramour, but the intrigues required in conducting adultery fed Cornwell’s craving for the duplicity and deception of spycraft. Morris’ documentary—which includes his trademark stylized reenactments and clips from film adaptations of le Carré novels, as well as extensive interviews with Cornwell conducted a few years before his death—allows his subject to expound at length on “the addiction, the fun of betrayal” in which “the joy is the voluptuous journey of constantly challenging your luck and surviving.” Cornwell was speaking then of Kim Philby, a notorious mole for the Soviet Union within the British intelligence service, but no one even glancingly aware of Cornwell’s complicated love life could miss the choice of voluptuous.

All of this is pretty sordid, and le Carré devotees will likely be offended by the fascination it engenders. But yet another reason Cornwell’s adulteries loom so large is simply that he wished them kept secret. He surely wanted to avoid publicly humiliating his wife (and indispensable amanuensis), Jane, or causing trouble for former lovers who were married. Yet Cornwell also clearly got off on the secrecy, as the readers of spy fiction do. The whole point of espionage novels is to reveal the occult workings of politics and power, and the most enthralling tricks of the trade—the cutouts and dead drops, the aliases and concealed microdots—are all devices of secrecy. Nothing attracts as much attention as that which someone is trying to hide.

In his interview with Marchese, Morris insisted that what interested him about Cornwell is Cornwell’s interest in “philosophical questions.” I’m not sure I entirely buy this. The Pigeon Tunnel features a reenactment of a story Cornwell relates in his memoir—a story that, incidentally, may not even be true. Cornwell claims that when the British intelligence service MI6 relocated its headquarters, it finally opened an old safe in the inner sanctum of C, the agency’s head, assuming that it held some ultra-classified documents. It was empty, but a cranny behind it contained the trousers of Rudolf Hess, a Nazi leader who flew to Scotland in an ill-conceived attempt to negotiate peace with the United Kingdom. Pinned to the trousers was a note suggesting that they be scrutinized to determine the state of the German textile industry.

Both Cornwell and Morris find this anecdote funny and deeply significant. Cornwell observes that one of the attractions of the hidden world of espionage is that it promises that there is “some great secret to the nature of human behavior” to be learned. “You want the rolled-up parchment in the inmost room that tells you who runs your lives and why,” he continues. “But there is none.”

“And in the inmost room of ourselves,” Morris asks, “maybe there’s nothing there?” At this moment, Cornwell looks directly into the camera and replies, “In my case, that is true, yes.”

This feels like the emotional apex of the film, the moment when it strikes its truest note. Are these questions philosophical or psychological? The title The Pigeon Tunnel refers to a shooting range set up on the balcony of a hotel in Monte Carlo that Cornwell visited as a boy with his father—a con man, a chronic liar, and a womanizer. Pigeons kept in cages on the roof of the hotel were sent into tunnels that let out below the balcony. As they flew up into the air, hotel guests shot at them with rifles. Any birds that weren’t killed would return, as pigeons do, to the only home they knew, the cages on the roof, where the process was repeated. Le Carré explains that The Pigeon Tunnel had been the working title of many of his novels before he finally used it for his memoir.

The motif depicts a purgatorial, inescapable repetition, tied to Cornwell’s father, whom he despised. (Cornwell’s mother, who deserted the family when she got sick of her husband bringing his lovers and shady confederates to the house, is a more elusive figure.) Morris’ repetition of pigeon imagery through the film suggests how obliviously we replicate our parents’ flaws, and how difficult it is to fill the hollow left by parents incapable of love.

Morris doesn’t really have to get Cornwell to talk about his cheating ways and how they slaked his appetite for deception, performance, and betrayal. Everything in The Pigeon Tunnel comes back to this unspoken theme, again and again. The single moment when Cornwell addresses that which shall not be addressed shapes the whole of this cagey, brilliant film around that absence. Because he will not talk about it, it becomes the center. Cornwell may have died believing he’d never been analyzed. But he was wrong.